APT38: Details on New North Korean Regime-Backed Threat Group

Today, we are releasing details on a advanced persistent threat group that we believe is responsible for conducting financial crime on behalf of the North Korean regime, stealing millions of dollars from banks worldwide. The group is particularly aggressive; they regularly use destructive malware to render victim networks inoperable following theft. More importantly, diplomatic efforts, including the recent Department of Justice (DOJ) complaint that outlined attribution to North Korea, have thus far failed to put an end to their activity. We are calling this group APT38.

We are releasing a special report, APT38: Un-usual Suspects, to expose the methods used by this active and serious threat, and to complement earlier efforts by others to expose these operations, using FireEye’s unique insight into the attacker lifecycle.

We believe APT38’s financial motivation, unique toolset, and tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) observed during their carefully executed operations are distinct enough to be tracked separately from other North Korean cyber activity. There are many overlapping characteristics with other operations, known as “Lazarus” and the actor we call TEMP.Hermit; however, we believe separating this group will provide defenders with a more focused understanding of the adversary and allow them to prioritize resources and enable defense. The following are some of the ways APT38 is different from other North Korean actors, and some of the ways they are similar:

- We find there are clear distinctions between APT38 activity and the activity of other North Korean actors, including the actor we call TEMP.Hermit. Our investigation indicates they are disparate operations against different targets and reliance on distinct TTPs; however, the malware tools being used either overlap or exhibit shared characteristics, indicating a shared developer or access to the same code repositories. As evident in the DOJ complaint, there are other shared resources, such as personnel who may be assisting multiple efforts.

- A 2016 Novetta report detailed the work of security vendors attempting to unveil tools and infrastructure related to the 2014 destructive attack against Sony Pictures Entertainment. This report detailed malware and TTPs related to a set of developers and operators they dubbed “Lazarus,” a name that has become synonymous with aggressive North Korean cyber operations.

- Since then, public reporting attributed additional activity to the “Lazarus” group with varying levels of confidence primarily based on malware similarities being leveraged in identified operations. Over time, these malware similarities diverged, as did targeting, intended outcomes and TTPs, almost certainly indicating that this activity is made up of multiple operational groups primarily linked together with shared malware development resources and North Korean state sponsorship.

Since at least 2014, APT38 has conducted operations in more than 16 organizations in at least 13 countries, sometimes simultaneously, indicating that the group is a large, prolific operation with extensive resources. The following are some details about APT38 targeting:

- The total number of organizations targeted by APT38 may be even higher when considering the probable low incident reporting rate from affected organizations.

- APT38 is characterized by long planning, extended periods of access to compromised victim environments preceding any attempts to steal money, fluency across mixed operating system environments, the use of custom developed tools, and a constant effort to thwart investigations capped with a willingness to completely destroy compromised machines afterwards.

- The group is careful, calculated, and has demonstrated a desire to maintain access to a victim environment for as long as necessary to understand the network layout, required permissions, and system technologies to achieve its goals.

- On average, we have observed APT38 remain within a victim network for approximately 155 days, with the longest time within a compromised environment believed to be almost two years.

- In just the publicly reported heists alone, APT38 has attempted to steal over $1.1 billion dollars from financial institutions.

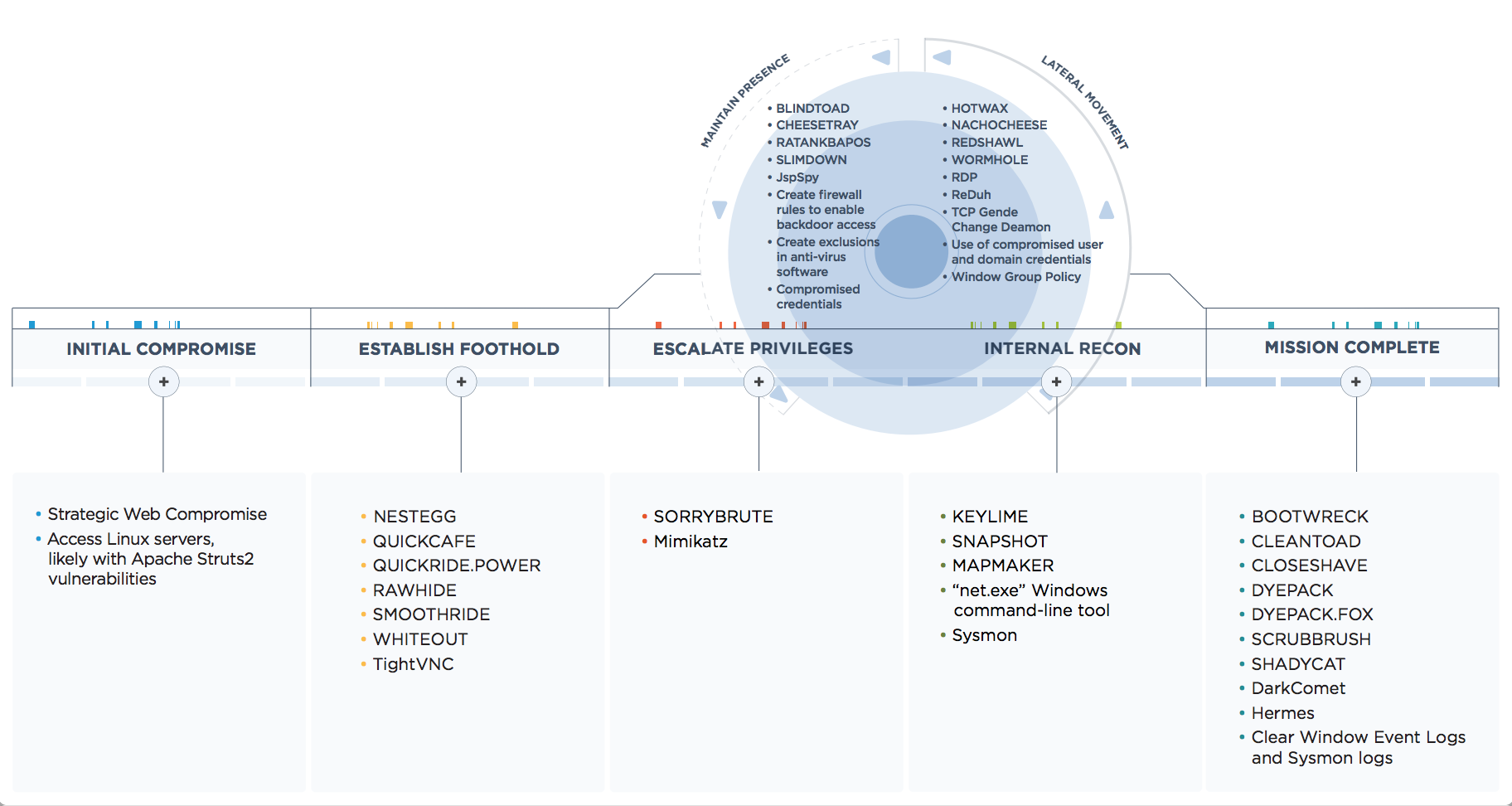

Investigating intrusions of many victimized organizations has provided us with a unique perspective into APT38’s entire attack lifecycle. Figure 1 contains a breakdown of observed malware families used by APT38 during the different stages of their operations. At a high-level, their targeting of financial organizations and subsequent heists have followed the same general pattern:

- Information Gathering: Conducted research into an organization’s personnel and targeted third party vendors with likely access to SWIFT transaction systems to understand the mechanics of SWIFT transactions on victim networks (Please note: The systems in question are those used by the victim to conduct SWIFT transactions. At no point did we observe these actors breach the integrity of the SWIFT system itself.).

- Initial Compromise: Relied on watering holes and exploited an insecure out-of-date version of Apache Struts2 to execute code on a system.

- Internal Reconnaissance: Deployed malware to gather credentials, mapped the victim’s network topology, and used tools already present in the victim environment to scan systems.

- Pivot to Victim Servers Used for SWIFT Transactions: Installed reconnaissance malware and internal network monitoring tools on systems used for SWIFT to further understand how they are configured and being used. Deployed both active and passive backdoors on these systems to access segmented internal systems at a victim organization and avoid detection.

- Transfer funds: Deployed and executed malware to insert fraudulent SWIFT transactions and alter transaction history. Transferred funds via multiple transactions to accounts set up in other banks, usually located in separate countries to enable money laundering.

- Destroy Evidence: Securely deleted logs, as well as deployed and executed disk-wiping malware, to cover tracks and disrupt forensic analysis.

APT38 is unique in that it is not afraid to aggressively destroy evidence or victim networks as part of its operations. This attitude toward destruction is probably a result of the group trying to not only cover its tracks, but also to provide cover for money laundering operations.

In addition to cyber operations, public reporting has detailed recruitment and cooperation of individuals in-country to support with the tail end of APT38’s thefts, including persons responsible for laundering funds and interacting with recipient banks of stolen funds. This adds to the complexity and necessary coordination amongst multiple components supporting APT38 operations.

Despite recent efforts to curtail their activity, APT38 remains active and dangerous to financial institutions worldwide. By conservative estimates, this actor has stolen over a hundred million dollars, which would be a major return on the likely investment necessary to orchestrate these operations. Furthermore, given the sheer scale of the thefts they attempt, and their penchant for destroying targeted networks, APT38 should be considered a serious risk to the sector.