Bring Your Own Land (BYOL) – A Novel Red Teaming Technique

Introduction

One of most significant recent developments in sophisticated offensive operations is the use of “Living off the Land” (LotL) techniques by attackers. These techniques leverage legitimate tools present on the system, such as the PowerShell scripting language, in order to execute attacks. The popularity of PowerShell as an offensive tool culminated in the development of entire Red Team frameworks based around it, such as Empire and PowerSploit. In addition, the execution of PowerShell can be obfuscated through the use of tools such as “Invoke-Obfuscation”. In response, defenders have developed detections for the malicious use of legitimate applications. These detections include suspicious parent/child process relationships, suspicious process command line arguments, and even deobfuscation of malicious PowerShell scripts through the use of Script Block Logging.

In this blog post, I will discuss an alternative to current LotL techniques. With the most current build of Cobalt Strike (version 3.11), it is now possible to execute .NET assemblies entirely within memory by using the “execute-assembly” command. By developing custom C#-based assemblies, attackers no longer need to rely on the tools present on the target system; they can instead write and deliver their own tools, a technique I call Bring Your Own Land (BYOL). I will demonstrate this technique through the use of a custom .NET assembly that replicates some of the functionality of the PowerSploit project. I will also discuss how detections can be developed around BYOL techniques.

Background

At DerbyCon last year, I had the pleasure of meeting Raphael Mudge, the developer behind the Cobalt Strike Remote Access Tool (RAT). During our discussion, I mentioned how useful it would be to be able to load .NET assemblies into Cobalt Strike beacons, similar to how PowerShell scripts can be imported using the “powershell-import” command. During a previous Red Team engagement I had been involved in, the use of PowerShell was precluded by the Endpoint Detection and Response (EDR) agent present on host machines within the target environment. This was a significant issue, as much of my red teaming methodology at the time was based on the use of various PowerShell scripts. For example, the “Get-NetUser” cmdlet of the PowerView script allows for the enumeration of domain users within an Active Directory environment. While the use of PowerShell was not an option, I found that no application-based whitelisting was occurring on hosts within the target’s environment. Therefore, I started converting the PowerShell functionality into C# code, compiling assemblies locally as Portable Executable (PE) files, and then uploading the PE files onto target machines and executing them. This tactic was successful, and I was able to use these custom assemblies to elevate privileges up to Domain Admin within the target environment.

Raphael agreed that the ability to load these assemblies in-memory using a Cobalt Strike beacon would be useful, and about 8 months later this functionality was incorporated into Cobalt Strike version 3.11 via the “execute-assembly” command.

“execute-assembly” Demonstration

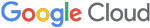

For this demonstration, a custom C# .NET assembly named “get-users” was used. This assembly replicated some of the functionality of the PowerView “Get-NetUser” cmdlet; it queried the Domain Controller of the specified domain for a list of all current domain accounts. Information obtained included the “SAMAccountName”, “UserGivenName”, and “UserSurname” properties for each account. The domain is specified by passing its FQDN as an argument, and the results are then sent to stdout. The assembly being executed within a Cobalt Strike beacon is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Using the “execute-assembly” command within a Cobalt Strike beacon.

Simple enough, now let’s take a look at how this technique works under the hood.

How “execute-assembly” Works

In order to discover more about how the “execute-assembly” command works, the execution performed in Figure 1 was repeated with the host running ProcMon. The results of the process tree from ProcMon after execution are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Process tree from ProcMon after executing “execute-assembly” command.

In Figure 2, The “powershell.exe (2792)” process contains the beacon, while the “rundll32.exe (2708)” process is used to load and execute the “get-users” assembly. Note that “powershell.exe” is shown as the parent process of “rundll32.exe” in this example because the Cobalt Strike beacon was launched by using a PowerShell one-liner; however, nearly any process can be used to host a beacon by leveraging various process migration techniques. From this information, we can determine that the “execute-assembly” command is similar to other Cobalt Strike post-exploitation jobs. In Cobalt Strike, some functions are offloaded to new processes, in order to ensure the stability of the beacon. The rundll32.exe Windows binary is used by default, although this setting can be changed. In order to migrate the necessary code into the new process, the CreateRemoteThread function is used. We can confirm that this function is utilized by monitoring the host with Sysmon while the “execute-assembly” command is performed. The event generated by the use of the CreateRemoteThread function is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: CreateRemoteThread Sysmon event, created after performing the “execute-assembly” command.

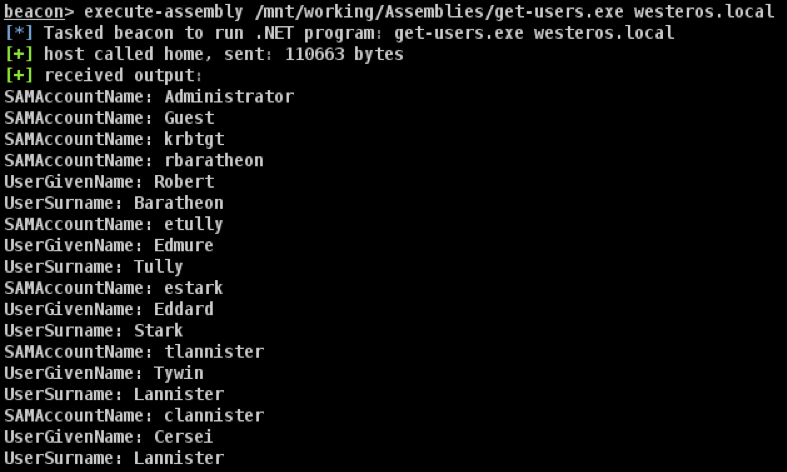

More information about this event is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Detailed information about the Sysmon CreateRemoteThread event shown in Figure 3.

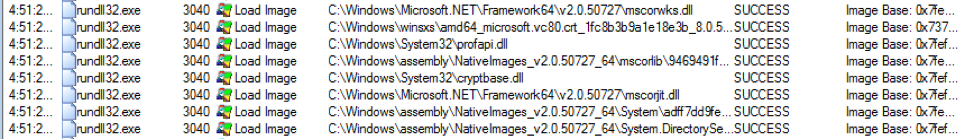

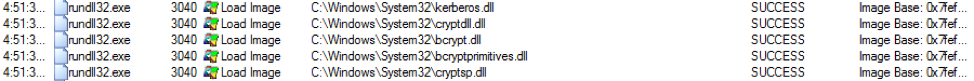

In order to execute the provided assembly, the Common Language Runtime (CLR) must be loaded into the newly created process. From the ProcMon logs, we can determine the exact DLLs that are loaded during this step. A portion of these DLLs are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Example of DLLs loaded into rundll32 for hosting the CLR.

In addition, DLLs loaded into the rundll32 process include those necessary for the get-users assembly, such as those for LDAP communication and Kerberos authentication. A portion of these DLLs are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Example of DLLs loaded into rundll32 for Kerberos authentication.

The ProcMon logs confirm that the provided assembly is never written to disk, making the “execute-assembly” command an entirely in-memory attack.

Detecting and Preventing “execute-assembly”

There are several ways to protect against the “execute-assembly” command. As previously detailed, because the technique is a post-exploitation job in Cobalt Strike, it uses the CreateRemoteThread function, which is commonly detected by EDR solutions. However, it is possible that other implementations of BYOL techniques would not require the use of the CreateRemoteThread function.

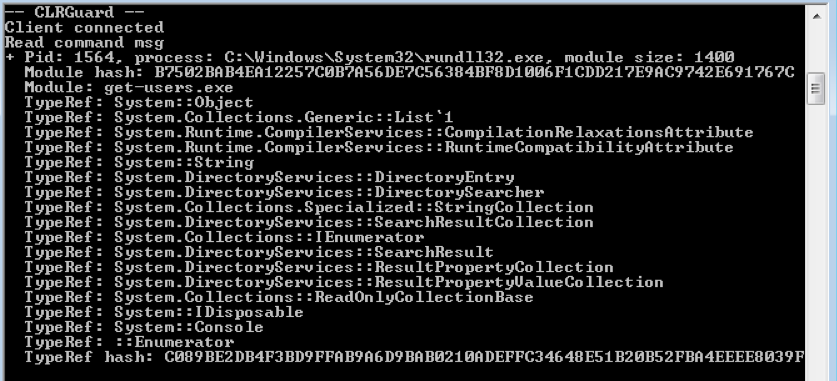

The “execute-assembly” technique makes use of the native LoadImage function in order to load the provided assembly. The CLRGuard project hooks into the use of this function, and prevents its execution. An example of CLRGuard preventing the execution of the “execute-assembly” command is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: CLRGuard blocking the execution of the “execute-assembly” technique.

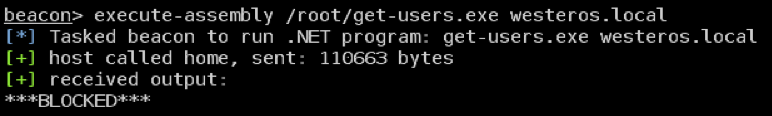

The resulting error is shown on the Cobalt Strike teamserver in Figure 8.

Figure 8: Error shown in Cobalt Strike when “execute-assembly” is blocked by CLRGuard.

While CLRGuard is effective at preventing the “execute-assembly” command, as well as other BYOL techniques, it is likely that blocking all use of the LoadImage function on a system would negatively impact other benign applications, and is not recommended for production environments.

As with almost all security issues, baselining and correlation is the most effective means of detecting this technique. Suspicious events to correlate could include the use of the LoadImage function by processes that do not typically utilize it, and unusual DLLs being loaded into processes.

Advantages of BYOL

Due to the prevalent use of PowerShell scripts by sophisticated attackers, detection of malicious PowerShell activity has become a primary focus of current detection methodology. In particular, version 5 of PowerShell allows for the use of Script Block Logging, which is capable of recording exactly what PowerShell scripts are executed by the system, regardless of obfuscation techniques. In addition, Constrained Language mode can be used to restrict PowerShell functionality. While bypasses exist for these protections, such as PowerShell downgrade attacks, each bypass an attacker attempts is another event that a defender can trigger off of. BYOL allows for the execution of attacks normally performed by PowerShell scripts, while avoiding all potential PowerShell-based alerts entirely.

PowerShell is not the only native binary whose malicious use is being tracked by defenders. Other common binaries that can generate alerts on include WMIC, schtasks/at, and reg. The functionality of all these tools can be replicated within custom .NET assemblies, due to the flexibility of C# code. By being able to perform the same functionality as these tools without using them, alerts that are based on their malicious use are rendered ineffective.

Finally, thanks to the use of reflective loading, the BYOL technique can be performed entirely in-memory, without the need to write to disk.

Conclusion

BYOL presents a powerful new technique for red teamers to remain undetected during their engagements, and can easily be used with Cobalt Strike’s “execute-assembly” command. In addition, the use of C# assemblies can offer attackers more flexibility than similar PowerShell scripts can afford. Detections for CLR-based techniques, such as hooking of functions used to reflectively load assemblies, should be incorporated into defensive methodology, as these attacks are likely to become more prevalent as detections for LotL techniques mature.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Casey Erikson, who I have worked closely with on developing C# assemblies that leverage this technique, for his contributions to this blog.