Fuzzing Image Parsing in Windows, Part Three: RAW and HEIF

Automated testing of Windows Image Libraries uncovers 37 security issues, including Zero-Click Code Execution with CVSS score of 7.8. All vulnerabilities have been remediated by Microsoft following the disclosure by Mandiant.

Continuing our discussion of image parsing vulnerabilities in Windows, we take a look at two of the file types supported by Windows: RAW and High Efficiency Image File Format (HEIF).

RAW files have been supported by Windows Camera Codec Pack since the Windows XP days and later Windows versions include these codecs by default. The codec file is present as WindowsCodecsRaw.dll in the system32 folder. The RAW codec is Windows Imaging Component (WIC) enabled, which means any program using WIC should be able to load and decode RAW images without any additional code. This enables Explorer to display thumbnails and previews and enables Microsoft.Photos.exe to display supported RAW images. Having WIC enabled codecs helped us avoid writing a new fuzzing harness, because the WIC and Component Object Model (COM) handles the detection of file formats and the loading of corresponding codecs. Even though this was very useful to quickly start our fuzzing, it came with a heavy performance tax (10 - 30x slowdown) due to the way COM works.

The codec supports RAW files from multiple camera manufactures, such as: Canon, Casio, Epson, Fujifilm, Kodak, Konica Minolta, Leica, Nikon, Olympus, Panasonic, Pentax, Samsung, Sony and a variety of other camera models. On the surface this is a very attractive attack surface given the number of supported camera models and manufacturers; unfortunately, most of the supported file formats are TIFF or based on the TIFF file format.

For fuzzing the RAW codec, we use a generic WIC harness and use WindowsCodecsRaw.dll as the code coverage module. The corpuses were collected from various public places and sizes were minimized by sacrificing some percentage of code coverage. This is needed due to the large file size of RAW files.

In our fuzzing, we found two integer overflow vulnerabilities in the library’s parsing of Canon CR2 format RAW files, and 35 vulnerabilities in the parsing of HEIF files. We present details of the most notable findings in this blog post.

CVE-2020-16968

CVE-2020-16968 is an integer overflow leading to a heap overflow while parsing a specially crafted Canon CR2 file.

Crash details are shown in Figure 1.

|

Figure 1: RAW codec crash

The root cause of the bug can be found by looking at the allocation of the object at WindowsCodecsRaw!POBitmapImageRep::init in Figure 2.

|

Figure 2: Vulnerable function

POBitmapImageRep::init accepts multiple heights and widths associated with camera sensors and does a cursory validation of the values they accept. These values are retrieved from the image file and thus are user controllable. The vulnerability arises from the fact that even with the initial validation, a 32-bit multiplication of the sensor height and width can cause an integer overflow and trigger a smaller heap memory allocation than needed. Additionally, POBitmapImageRep::init is a generic function used to allocate memory and is used by multiple RAW file formats from different manufacturers. It is very likely that different file formats may also trigger the same vulnerability.

Sample values which cause integer overflow are provided in Figure 3.

|

Figure 3: Integer overflow calculations

The resulting heap memory allocated by POBitmapImageRep::init is used to store data from the image file. This is performed using the two nested for loops of row by columns. The underlying code in CCanonSRawLoadRaw::lossless_jpeg_load_raw is the result of a port of the function from the dcraw library to C++.

Variant Analysis

A variant of this vulnerability can be easily found by cross referencing HeapAlloc usage in other parts of the code. CCanonSRawLoadRaw::GetBitmapImage contained a similar pattern of integer overflow leading to an heap overflow. Microsoft decided to patch this as a separate vulnerability, CVE-2020-0997.

Patch

Microsoft patched both integer overflows by promoting the multiplication to 64-bit and bailing out if the result is greater than 4 GiB as shown in Figure 4.

|

Figure 4: CVE-2020-16968 patch

HEIF

High Efficiency Image File Format (HEIF) is a newer and more dynamic container format for images and image sequences based on the ISO Base Media File Format (ISOBMFF). Windows 10 supports HEIF through the HEIF Image Extension Windows Store app. The HEIF Image Extension is also WIC enabled, allowing us to use the older harness to access HEIF decoders without any changes to our fuzzer.

As HEIF is a container format, it supports multiple compression formats, namely:

- Advanced Video Coding (AVC) in HEIF (AVCI)

- High Efficiency Video Coding (HEVC) in HEIF (HEIC)

- AOMedia Video 1 (AV1) in HEIF (AVIF)

The HEIF Image Extension from the Windows Store supports basic HEIF containers with AVC support. To decode HEVC or AV1, additional extensions must be installed. While the AV1 extension support is based on the open source libavif, HEVC seems to be Microsoft's proprietary code base and requires a payment of $0.99 to install the extension (likely due to complex HEVC licensing terms). All of the extensions are WIC enabled and HEIF loads the corresponding extensions based on the detected file format, eliminating the need of a new harness.

For fuzzing HEIF, I decided to gather three separate corpus sets based on their file headers and fuzz them based on the likelihood of finding vulnerabilities. I spent the least amount with fuzzing AVIF, because its support is based on the libavif code which is regularly fuzzed by OSSFuzz and other researchers. Only a moderate amount of time was spent on the AVC extension, given the prevalence of AVC codec and the most of my time was spent on the new HEVC extension for being a relatively new codec.

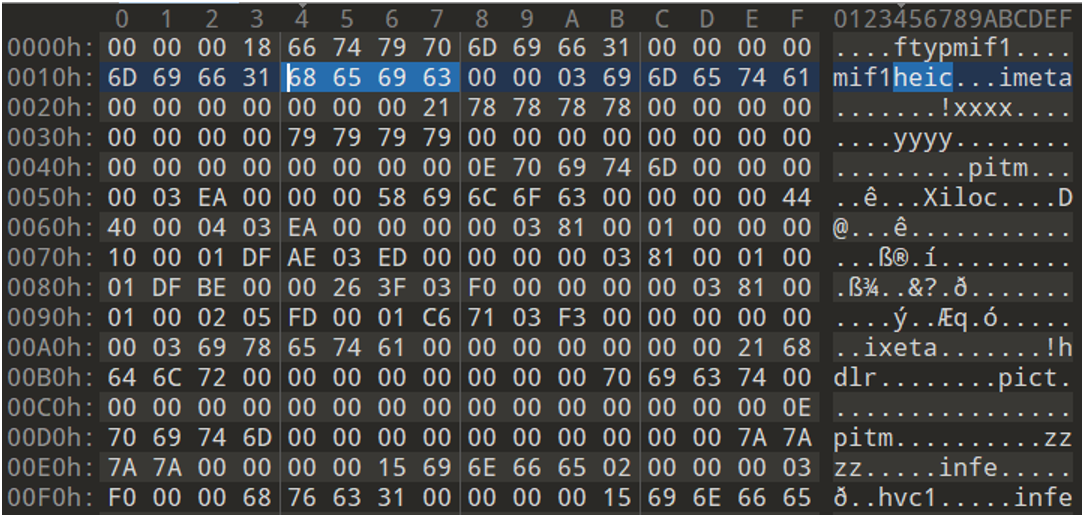

Fuzzing these codecs ended up more fruitful than I could have imagined. After triaging hundreds of crashes, a total of 35 vulnerabilities were reported to the Microsoft Response Center (MSRC), resulting in 21 CVEs. Most of the crashes were from the HEVC extension and the least were from the AVIF extension. Let me explain to you an interesting case of heap use after free (UAF) that I found in the HEIF extension. An example crash of the aforementioned UAF vulnerability (CVE-2020-17101) is presented in Figure 5.

|

Figure 5: HEIF crash

CVE-2020-17101’s use-after-free happens in the very early stage of the ISOBMFF header parsing. The code path can be invoked by thumbnail creation, which essentially makes this a zero-click Remote Code Execution (RCE). What helps enable this RCE is that thumbnails are turned on by default in Windows Explorer.

ISOBMFF uses boxes or atoms to encapsulate data stored in the representative file. Each box contains a length field (4 bytes), box name (fourCC byte sequence), and optional metadata and data. The data can contain other boxes and corresponding metadata.

Basic box parsing starts from the bytes "ftyp" (offset 4 in Figure 6) and looks for a supported brand. Here, "mif1" is the brand and "heic" is the image collection brand. In a normal parsing scenario, "mif1" is followed by a "meta" box, which encapsulates other boxes such as "hdlr", "iloc", "iinf", "pitm" etc.

When parsing the Proof of Concept (PoC) file (Figure 6), the "meta" box is followed by an "xxxx" generic box (instead of "hdlr" and "pict"). As "pict" is missing, the parsing code assumes the following boxes "pitm" and "iloc" as generic boxes and not as a "typed box". When the parsing reaches the "hdlr" box, "hdlr" and "pict" boxes are parsed as a typed box and the "meta" object is updated to mark the found "pict" box. Now the parsing reaches the second "pitm" box and is considered as a typed box, the pointer is updated in the "meta" object. The next box "zzzz" is parsed as a generic box and attached to the new "pitm" object. All the initial parsing happens in the CQTAtom::ScanChildren function.

When parsing reaches the end and calls the CHEIFImage::FinalParseAtom function, it checks whether "iloc", "iinf", and "pitm" boxes were found. If any of those boxes are missing, destructors of the objects are called for cleanup (objects are reference counted), and parsing is restarted by calling the function CQTAtom::ScanChildren. The destructor frees the "zzzz" box which is attached to "pitm", but the stored pointer to "zzzz" object is not nulled from the "pitm" object.

When the parsing restarts, the "meta" object already has "pict", and then "xxxx" is parsed as a generic box, but "pitm" and "iloc" (offset 0x49 and 0x57 in Figure 6) are parsed as typed boxes. As we already have "pitm", its reference count is incremented (instead of full parsing) and "iloc" is parsed. This parsing fails and the code bails out with an error.

As the parsing has failed, the objects are destroyed once again. The destructor loops over the linked list and calls every object's destructor. As the "pitm" object still has a pointer reference to the freed "zzzz" object, the code tries to free the "zzzz" object a second time by accessing the freed object's virtual function table and calling the destructor as a virtual function. This causes the crash, as we have enabled page heap for the fuzzed process.

Patch

Microsoft patched the vulnerability by nulling the saved pointer reference after freeing the memory.

Conclusion

Part three of this blog series presents multiple vulnerabilities in Window’s built-in image parsers and introduces newer image formats supported by Windows. A list of all reported vulnerabilities can be found in the following appendix and found referenced in the Mandiant Vulnerability Disclosures.

Appendix

| CVE id | Submitted Date | Fixed Date | Vulnerability type |

| CVE-2020-0997 | 01-July-2020 | 08-September-2020 | Integer overflow |

| CVE-2020-16968 | 01-July-2020 | 13-October-2020 | Integer overflow |

| CVE-2020-17022 | 03-July-2020 | 13-October-2020 | Heap/Stack overflow |

| CVE-2021-24110 | 07-July-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-1643 | 08-July-2020 | 12-January-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2020-17101 | 10-July-2020 | 10-November-2020 | Use After Free |

| CVE-2020-17107 | 13-July-2020 | 10-November-2020 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2020-17106 | 13-July-2020 | 10-November-2020 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2020-17108 | 21-July-2020 | 10-November-2020 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2020-17109 | 30-July-2020 | 10-November-2020 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2020-17105 | 13-August-2020 | 10-November-2020 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2020-17110 | 31-August-2020 | 10-November-2020 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-27048 | 14-October-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-27047 | 14-October-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-27049 | 14-October-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-27051 | 14-October-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-26902 | 23-October-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-27061 | 23-October-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-24089 | 23-October-2020 | 09-March-2021 | Heap/Stack overflow |

| CVE-2021-33775 | 24-March-2021 | 13-July-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-33777 | 24-March-2021 | 13-July-2021 | Uninitialized memory |

| CVE-2021-33778 | 24-March-2021 | 13-July-2021 | Heap overflow |

| CVE-2021-38661 | 27-April-2021 | 14-September-2021 | Heap overflow |