Using Precalculated String Hashes when Reverse Engineering Shellcode

In the five years I have been a part of Mandiant's malware analysis team (now formally known as M-Labs) there have been times when I've had to reverse engineer chunks of shellcode. In this post I will give some background on shellcode import resolution techniques and how to automate IDA markup to allow faster shellcode reverse engineering.

Reversing Shellcode

The easiest way to determine what a piece of shellcode does is to allow it to run within a monitored environment. This may not work if the shellcode is launched by an exploit and you don't have the correct version of the vulnerable program. In our experience working with shellcode we've seen many malware samples that contain an embedded shellcode buffer that is injected into other processes to execute. However, getting this embedded piece of shellcode to run correctly may not always to be feasible. Static analysis of the shellcode may be required in these types of situations to determine its functionality.

Shellcode binaries are typically not very large, so they don't present a huge challenge to reverse engineer, but common techniques shellcode authors employ often have a side-effect of hampering reverse engineering. One such technique is using hashes of API function when manually resolving import functions.

Shellcode Import Resolution

A developer writing a normal program can use kernel32.dll's LoadLibraryA and GetProcAddress to load arbitrary DLLs and retrieve its exported function pointers. Shellcode authors usually face size constraints, so including the full string of each API function it wishes to use could be prohibitive. Rather than using the full string, a more size efficient method is to pre-compute numeric hashes of function names and include these values in the shellcode. This changes the import resolution process as shellcode can no longer rely on GetProcAddressto retrieve the function pointers. Instead it must parse the DLL PE files in memory to find the export directory and traverse its array of export functions. For each export function name, the shellcode calculates the hash and compares it against the value embedded in the shellcode. The correct API function has been found when the values match. Background information on this technique can be found in the paper that was released by the Last Stage of Delirium as part of their winasmproject (http://lsd-pl.net/projects/winasm.zip).

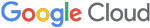

This may sound difficult, but luckily most shellcode authors reuse known hash algorithms and values, making the life of the reverse engineer much better. The most common hash function that I've seen in recovered shellcode samples is included with Metasploit. The algorithm is shown in pseudocode in Figure 1.

The hash is in no way a strong cryptographic hash, but it accomplishes the goal of calculating an integer value based on an arbitrary length input string. The only real constraint on the hash algorithm is that every API function the developer wishes to use within a DLL must have a unique hash value, and this simple ROR-13 calculation is very effective. Unusual hashes that I've come across are usually slight variant of this idea: they may rotate by a different amount, rotate left rather than right, or use some other operators to mix all of the characters in the input string to form an integer result.

Automating Shellcode Import Markup

When first starting to reverse engineer shellcode you'll most likely search online for these magic values, or calculate these values yourself and store them in a text file for future reference. Over time, as I reviewed more samples, I realized this was an annoying and repetitive task that is ripe for automation through IDA scripting.

Due to frequent code reuse among shellcode authors, I felt releasing my set of IDA scripts would be helpful to malware analysts. Pre-computing common API function names using known hash algorithms is feasible, and if a new hash algorithm is encountered it likely will not be too difficult to implement to generate its hashes. There has only been one instance, involving string hash from Poison Ivy RAT, in which this wasn't the case.

You may find the scripts at the Mandiant GitHub repository: https://github.com/mandiant/Reversing.

There are two parts:

make_sc_hash_db.pyis responsible for the pre-calculation of function names hashes. It is a command-line Python script that contains an implementation of the hash algorithms I've encountered in the past. It processes a directory of DLLs, calculates the hash of each export function and stores all of these into an SQLite database.shellcode_hash_search.py is an IDAPython script that opens the SQLite database containing the precalculated hashes and searches through the current binary for known hashes.

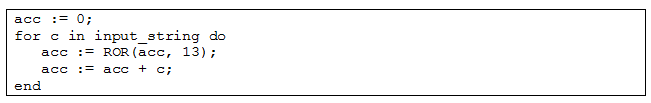

make_sc_hash_db.py can be run as shown in Figure 2, where the first argument is the SQLite database name to create and the second argument is the directory containing interesting DLLs. If you prefer to skip this step, a sample database is included within the distribution.

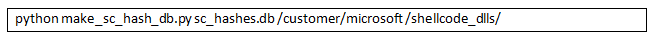

When the shellcode_hash_search.py IDAPython script runs it prompts the user for the database to use and then queries the user for additional search parameters. It shows all of the hash algorithms stored in the database and provides some simple pseudocode as shown in Figure 3. The script tries to use PySide Python bindings for QT that HexRays distributes (available as a separate download for IDA here http://www.hex-rays.com/products/ida/support/download.shtml). If the HexRays distribution of PySide is not included, it falls back to presenting a series of simple dialogs to get the same information from the user.

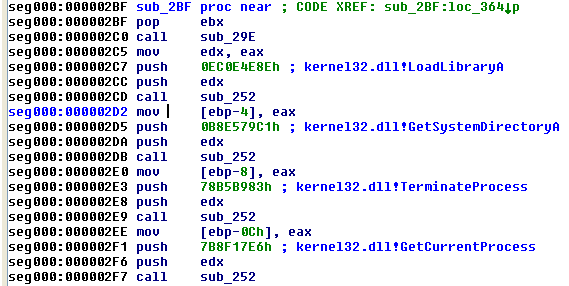

If nothing has been highlighted, the script searches through the highlighted region or the current segment. The searching process queries each DWORD (if the DWORD Array option is checked) and each instruction operand (if the Instr Operands option is checked) to determine if that is a known hash for the selected hash algorithms. When a hash value is found a line comment is added in IDA as shown in Figure 4.

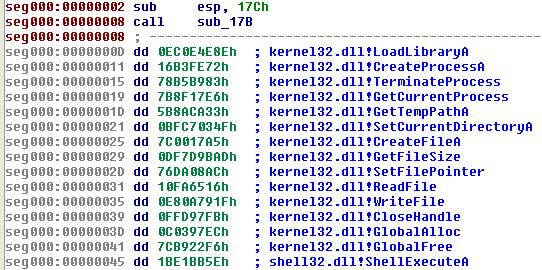

It's also common for shellcode authors to use DWORD arrays of hashes rather than pushing each one as a function argument, and this is shown in Figure 5.

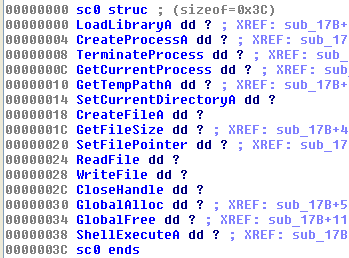

If the Create Struct option is checked and hash values are found at consecutive addresses the script creates an IDA structure as shown in Figure 6.

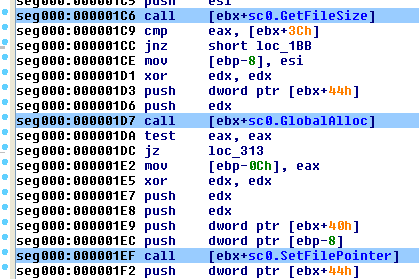

This structure may be useful if the shellcode authors treat this as an array of function pointers, as it allows the analyst to convert [base+index] references into structure references. This is shown in Figure 7 where the call instructions are easier to understand by using known structure offsets.

The shellcode_hashes_search_plugin.py IDAPython plugin is provided if you would like this functionality available from IDA's plugins menu. Simply copy this file to your %PROGRAMFILES%IDAplugins directory and make sure the other python files are accessible by setting your PYTHONPATHenvironment variable correctly.

Conclusion

Frequently, reversing shellcode is much more tedious than reversing a typical binary. The lack of imports resolved by IDA is a big reason for the slowed reversing timeline. By using the IDAPython scripts we've described above, and released on our GitHub page, we hope your shellcode reversing will improve.