Financially Motivated Actors Are Expanding Access Into OT: Analysis of Kill Lists That Include OT Processes Used With Seven Malware Families

Mandiant Threat Intelligence has researched and written extensively on the increasing financially motivated threat activity directly impacting operational technology (OT) networks. Some of this research is available in our previous blog posts on industrial post-compromise ransomware and FireEye's approach to OT security. While most of the actors behind this activity likely do not differentiate between IT and OT or have a particular interest in OT assets, they are driven by the goal of making money and have demonstrated the skills needed to operate in these networks. For example, the shift to post-compromise ransomware deployment highlights the actors’ ability to adapt to more complex environments.

In this blog post we look further into this trend by examining two different process kill lists containing OT processes which we have observed deployed alongside a variety of ransomware samples and families. We think it is likely that these lists were the result of coincidental asset scanning in victim organizations and not specific targeting of OT. While this judgement may initially seem like good news to defenders, this activity still indicates that multiple, very prolific, financially motivated threat actors are active inside organizations’ OT—based on the contents of these process kill lists—with the intent of profiting from the ransom of stolen information and disrupted services.

Two Unique Process Kill Lists Deployed Alongside Seven Ransomware Families Include OT Processes

Threat actors often deploy process kill lists alongside or as part of ransomware to terminate anti-virus products, stop alternative detection mechanisms, and remove file locks to ensure critical data is encrypted. As a result, the deployment of these lists increases the likelihood of a successful attack (MITRE ATT&CK T1489). In post compromise ransomware attacks, attackers regularly tailor the lists to include processes that are relevant to the victim’s environment. By stopping these processes, the attacker makes sure to encrypt data from critical systems, which may remain unaffected if the process is currently in use. As the likelihood of crippling critical systems increases, the target is more likely to suffer impacts on its physical production.

First Process Kill List Has Been Leveraged By At Least Six Ransomware Families

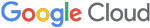

Mandiant identified samples of at least six ransomware families (DoppelPaymer, LockerGoga, Maze, MegaCortex, Nefilim and SNAKEHOSE)—all of which have been associated with high-profile incidents impacting industrial organizations over the past two years—that have leveraged a common process kill list containing 1,000+ processes. The list, which we briefly discussed in an earlier blog post from February 2020, includes a couple dozen processes related to OT executables—mainly from General Electric Proficy, a suite used for historians and human-machine interfaces (HMIs). We note, that while the inclusion of these processes in this kill list could result in limited loss of view of historical process data, it is not likely to directly impact the operator’s ability to control the physical process itself.

The earliest iteration we identified of the shared kill list was a batch script deployed alongside LockerGoga (MD5: 34187a34d0a3c5d63016c26346371b54) in January 2019 (Figure 1). Other iterations of the list we have observed are also hardcoded directly into the ransomware binaries. The different techniques used to deploy the process kill list, the use of different malware families, and slight variations between each list iteration (mainly typos in the processes, e.g.: a2guard.exea2start.exe; nexe; proficyclient.exe) indicate that likely more than one actor had access to the true source of the process kill list. This source could be for example a post of processes shared on a dark web forum, or an independent actor sharing the compiled list with other actors.

We think it is likely that the OT processes identified in this list simply represent the coincidental output of automated process collection from victim environment(s) and not a targeted effort to impact OT. This is supported by the relatively limited and specific selection of OT-related processes, rather than a broader selection of many vendors and OT-related processes that would have been suggestive of targeted external research. Regardless, this does not downplay the significance of the inclusion of OT processes in the list, as it suggests that sophisticated financially motivated actors, such as FIN6, have had at least some visibility into a victim’s OT network. As a result, the actors were able to tailor their malware to impact those systems, without the explicit intent to target OT assets.

Most types of ransomware attacks in OT environments will result in the disruption of services and a temporary loss of view into current and historical process data. However, OT environments impacted by a ransomware that leverages this kill list and happen to be running one or more of the processes used by the initial victim(s)—and therefore are included on the list—may face additional impacts. For example, historian databases would be more likely to be encrypted, possibly resulting in loss of historical data. Other impacts could include gaps in the collection of process data corresponding to the duration of the outage and temporary loss of access to licensing rights for critical services.

Second List Deployed Alongside CLOP Ransomware Sample Has a Higher Chance of Impacting OT Systems

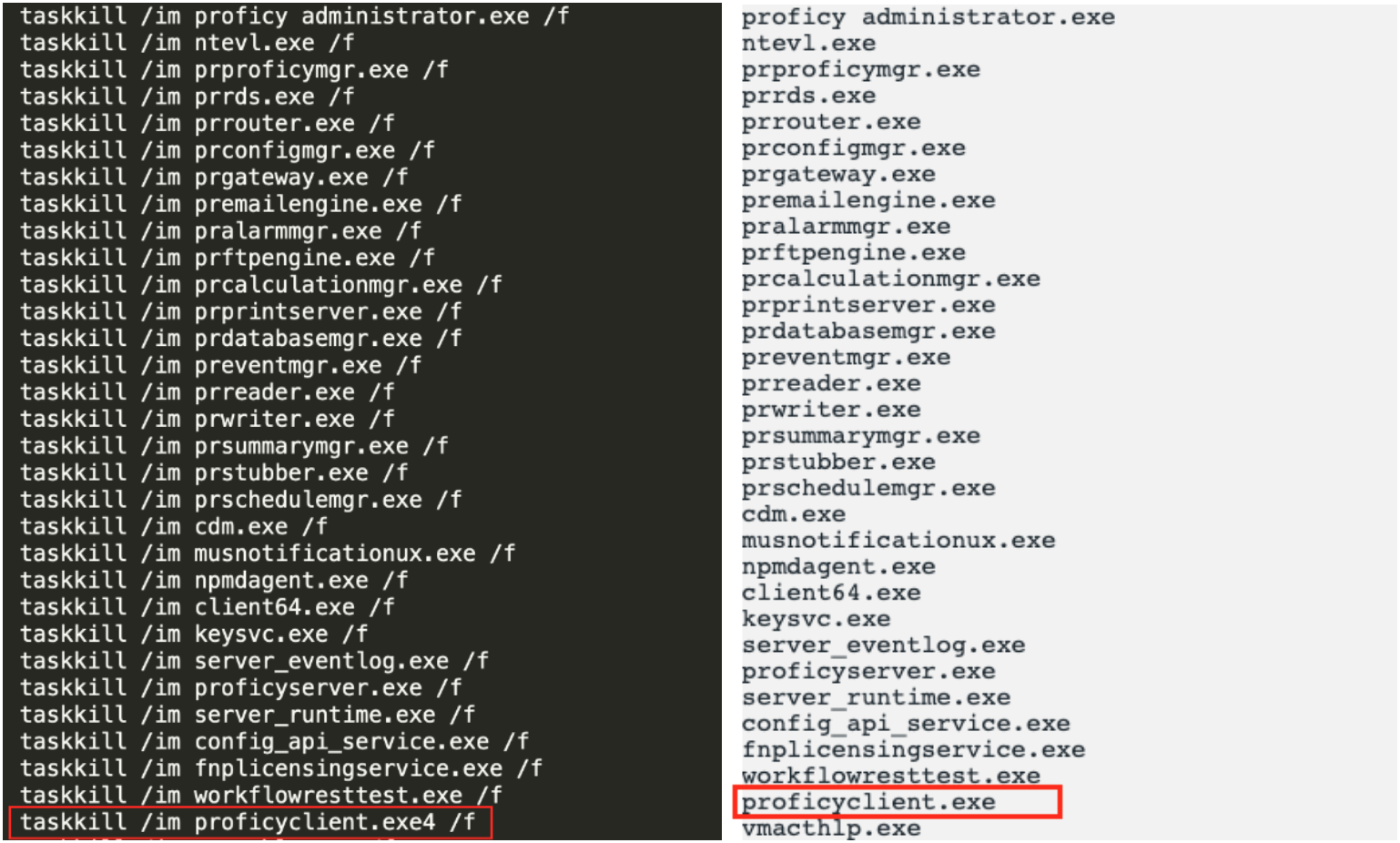

Mandiant analyzed a second, entirely unrelated sample of ransomware (MD5: 3b980d2af222ec909b948b6bbdd46319) from the CLOP family with a hardcoded list for enumeration and termination of processes that includes a number of OT strings. The list contains over 1,425 processes, from which at least 150 belong to OT-related software suites (Figure 2 and Appendix).

Based on our analysis, the CLOP malware family’s process kill list has grown over time possibly as more processes are scanned during different compromises. While we do not currently hold enough information to describe the exact mechanism used by the actor to grow the list, it appears to have resulted from actor reconnaissance across multiple victims. We have observed the threat actor employing process discovery procedures, including running the tasklist utility. This indicates that the actor scanned for processes in at least one victim’s OT network(s) before deploying the ransomware.

CLOP is also interesting as we have only observed a single unique and very prolific financially motivated threat actor leveraging the malware family. The group, who has been active since at least 2016 and potentially as early as 2014, is known for operating large phishing campaigns to distribute malware and typically monetizes intrusions through ransomware deployment. As highlighted by their versatility and long history in financially motivated intrusions, the actor’s activity in OT networks is likely no more than an additional step in the process for monetization. However, the financial motivations of the actor again do not imply low risk to OT. Instead, our analysis of the CLOP sample’s kill list indicates that the included processes actually have greater potential to disrupt OT systems than those included in the shared list described above.

Unlike the first kill list, the CLOP sample includes a list of processes that, if stopped, may directly impact the operator’s ability to both visualize and control production. This is especially true in the case of some included processes that support HMI and PLC supervision. Some of the OT processes present in the CLOP sample are related to the following products:

| Vendor | Product | Description |

| Siemens | SIMATIC WinCC | SCADA system, common for process control and automation. |

| Beckhoff | TwinCAT | Software for PC-based process control and automation. |

| National Instruments | Data Acquisition Software (DAQ) | Software used to acquire data from sensors and conditioning devices. |

| Kepware | KEPServer EX | Software platform that collects information from industrial devices and sends the output to SCADA applications. |

| OPC Unified Architecture (OPC-UA) | N/A | Communication protocol for data acquisition and exchange between industrial equipment and enterprise systems. |

Table 1: Examples of products related to OT processes included in identified CLOP kill list

While it is likely the physical processes this software controls would continue to operate even if the software processes were terminated unexpectedly, stopping the software processes included in the CLOP sample’s kill list could result in the loss of view/control over those physical processes due to the inability of operators to interact with the equipment. This can be caused not only by the ransomware’s disruption of intermediary systems, but also by the loss of access to relevant files on HMIs/EWS required for the operation of process control and monitoring software–for example configurations or project files. This could prolong the mean time to recovery (MTTR) of impacted environments without offline backups. In the CLOP sample list, we also identified specialized processes for software application design and testing that may also become corrupted at the time of encryption.

Process Kill Lists Are Just An Observable Indicating Broader Financially Motivated Interest In OT

Financially motivated threat actors leverage a large variety of tactics and techniques to obtain data that they can later use to generate profits. While financial actors have historically posed little to no threat to OT systems, the recent uptick in ransomware and extortion incidents highlights that industrial operations are increasingly at risk. Although we have not observed any financially motivated actors explicitly targeting OT systems, our research into process kill lists deployed with or alongside ransomware samples shows that at least two sophisticated financial actors have expanded their access into OT networks during their regular intrusions.

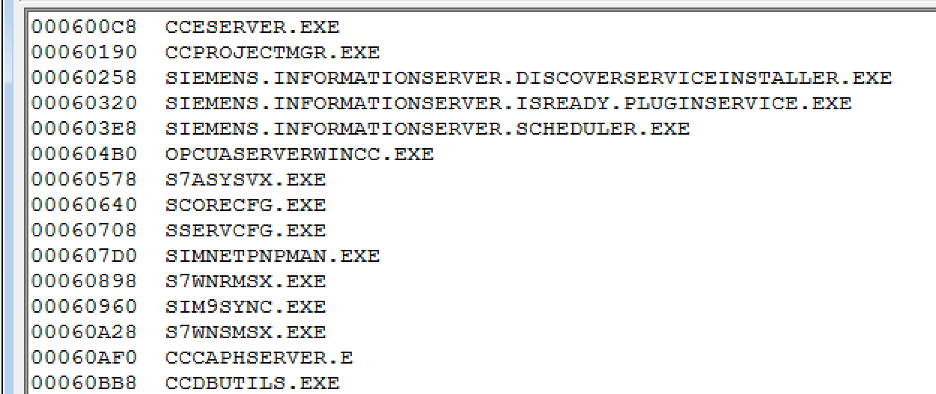

This increasing exposure of OT to financially motivated threat activity is no surprise, given that TTPs used by cybercriminals increasingly resemble those employed by sophisticated actors. We have consistently conveyed this message since at least 2018, when we publicly discussed the commodity and custom IT tools leveraged by the TRITON attacker while traversing through its targets’ networks (Figure 3). The likelihood of financially motivated actors impacting OT while seeking to monetize intrusions will continue to rise for the following reasons:

- Financially-motivated threat actors moving to a post-compromise ransomware model will continue to evolve and find ways to reach the most critical systems of organizations as part of their mission of monetization. As these actors are mainly driven by profits, they are not likely to differentiate between IT and OT assets.

- OT organizations will continue to struggle to evolve at the same pace as cyber criminals. As a result, small weaknesses such as misconfigurations, exposed vulnerabilities or improper segmentation will be enough for financial actors to gain access to networks in their attempts to profit from intrusions.

- As the market for OT solutions continues to incorporate IT services and features into broadly adopted products, we expect the convergence of technologies to result in a broader attack surface for financial threat actors to target.

- The TTPs employed by both financial and sophisticated nation-state actors often rely on intermediary systems as stepping stones through intrusions. As a result, the skills of both groups hold similar potential of reaching OT systems even when financial groups may only do so coincidentally or as part of their monetization strategy.

Outlook

As OT networks continue to become more accessible to threat actors of all motivations, security threats that have historically impacted primarily IT are becoming more commonplace. This normalization of OT as just another network from the threat actor perspective is problematic for defenders for many of the reasons discussed above. This recent threat activity should be taken as a wake-up call for two main reasons: the various security challenges commonly faced by organizations to protect OT networks, and the significant consequences that may arise from security compromises even when they are not explicitly designed to target production systems. Asset owners need to look at OT security with the mindset that it is not if you will have a breach, but when. This shift in thinking will allow defenders to better prepare to respond when an incident does happen, and can help reduce the impact of an incident by orders of magnitude.

Appendix: Selection Of OT Processes From CLOP Kill List

| Process Name | Vendor |

| ACTLICENSESERVER.EXE | Atlas Copco |

| TCATSYSSRV.EXE | Beckhoff |

| TCEVENTLOGGER.EXE | Beckhoff |

| TCR.EXE | Beckhoff |

| ALARMMANAGER.EXE | GE |

| S2.EXE | Honeywell |

| BR.ADI.DISPLAY.BRIGHTNESS.EXE | B&R |

| BR.ADI.SERVICE.EXE | B&R |

| BR.ADI.UPS.MANAGER.EXE | B&R |

| BR.ADI.UPS.SERVICE.EXE | B&R |

| BR.AS.UPGRADESERVICE.EXE | B&R |

| BRAUTHORIZATIONSVC.EXE | B&R |

| BRTOUCHSVC.EXE | B&R |

| OPCROUTER4SERVICE.EXE | Inray Industriesoftware |

| OPCROUTERCONFIG.EXE | Inray Industriesoftware |

| SERVER_EVENTLOG.EXE | Kepware |

| SERVER_RUNTIME.EXE | Kepware |

| NICELABELAUTOMATIONSERVICE2017.EXE | NiceLabel |

| NICELABELPROXY.EXE | NiceLabel |

| NICELABELPROXYSERVICE2017.EXE | NiceLabel |

| APPLICATIONWEBSERVER.EXE | National Instruments |

| CWDSS.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIAUTH_DAEMON.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIDEVMON.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIDISCSVC.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIDMSRV.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIERSERVER.EXE | National Instruments |

| NILXIDISCOVERY.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIMDNSRESPONDER.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIMXS.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIPXICMS.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIROCO.EXE | National Instruments |

| NISDS.EXE | National Instruments |

| NISVCLOC.EXE | National Instruments |

| NIWEBSERVICECONTAINER.EXE | National Instruments |

| SYSTEMWEBSERVER.EXE | National Instruments |

| OPC.UA.DISCOVERYSERVER.EXE | OPC |

| OPCUALDS.EXE | OPC |

| ANAWIN.EXE | AUTEM |

| ASM.EXE | Possibly Siemens |

| PARAMETRIC.EXE | PTC |

| QDAS_O-QIS.EXE | Q-Das |

| QDAS_PROCELLA.EXE | Q-Das |

| QDAS_QS-STAT.EXE | Q-Das |

| QDASIDI_SRV.EXE | Q-Das |

| SPCPROCESSLINK.EXE | Q-Das |

| TAGSRV.EXE | Rockwell Automation or National Instruments |

| _SIMPCMON.EXE | Siemens |

| ALMPANELPLUGIN.EXE | Siemens |

| ALMSRV64X.EXE | Siemens |

| ALMSRVBUBBLE64X.EXE | Siemens |

| CC.TUNNELSERVICEHOST.EXE | Siemens |

| CCAEPROVIDER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCAGENT.EXE | Siemens |

| CCALGRTSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCARCHIVEMANAGER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCCAPHSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCCSIGRTSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCDBUTILS.EXE | Siemens |

| CCDELTALOADER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCDMRUNTIMEPERSISTENCE.EXE | Siemens |

| CCECLIENT_X64.EXE | Siemens |

| CCECLIENT.EXE | Siemens |

| CCESERVER_X64.EXE | Siemens |

| CCESERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCKEYBOARDHOOK.EXE | Siemens |

| CCLICENSESERVICE.EXE | Siemens |

| CCNSINFO2PROVIDER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCPACKAGEMGR.EXE | Siemens |

| CCPERFMON.EXE | Siemens |

| CCPROFILESERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCPROJECTMGR.EXE | Siemens |

| CCPTMRTSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCREDUNDANCYAGENT.EXE | Siemens |

| CCREMOTESERVICE.EXE | Siemens |

| CCRT2XML.EXE | Siemens |

| CCRTSLOADER_X64.EXE | Siemens |

| CCSSMRTSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCSYSTEMDIAGNOSTICSHOST.EXE | Siemens |

| CCTEXTSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCTLGSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCTMTIMESYNC.EXE | Siemens |

| CCTMTIMESYNCSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCUCSURROGATE.EXE | Siemens |

| CCWATCHOPC.EXE | Siemens |

| CCWRITEARCHIVESERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| DA2XML.EXE | Siemens |

| GSCRT.EXE | Siemens |

| HMIES.EXE | Siemens |

| HMIRTM.EXE | Siemens |

| HMISMARTSTART.EXE | Siemens |

| HMRT.EXE | Siemens |

| IPCSECCOM.EXE | Siemens |

| OPCUASERVERWINCC.EXE | Siemens |

| PASSDBRT.EXE | Siemens |

| PDLRT.EXE | Siemens |

| PMEXP.EXE | Siemens |

| PNIOMGR.EXE | Siemens |

| REDUNDANCYCONTROL.EXE | Siemens |

| REDUNDANCYSTATE.EXE | Siemens |

| S7ACMGRX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7AHHLPX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7ASYSVX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7EPASRV64X.EXE | Siemens |

| S7HSPSVX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7KAFAPX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7O.TUNNELSERVICEHOST.EXE | Siemens |

| S7OIEHSX64.EXE | Siemens |

| S7OPNDISCOVERYX64.EXE | Siemens |

| S7SYMAPX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7TGTOPX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7TRACESERVICE64X.EXE | Siemens |

| S7UBTOOX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7UBTSTX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7WNRMSX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7WNSMGX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7WNSMSX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7XUDIAX.EXE | Siemens |

| S7XUTAPX.EXE | Siemens |

| SCORECFG.EXE | Siemens |

| SCOREDP.EXE | Siemens |

| SCOREPNIO.EXE | Siemens |

| SCORES7.EXE | Siemens |

| SCORESR.EXE | Siemens |

| SCSDISTSERVICEX.EXE | Siemens |

| SCSFSX.EXE | Siemens |

| SCSMX.EXE | Siemens |

| SDIAGRT.EXE | Siemens |

| SIEMENS.INFORMATIONSERVER.DISCOVERSERVICEINSTALLER.EXE | Siemens |

| SIEMENS.INFORMATIONSERVER.ISREADY.PLUGINSERVICE.EXE | Siemens |

| SIEMENS.INFORMATIONSERVER.SCHEDULER.EXE | Siemens |

| SIM9SYNC.EXE | Siemens |

| SIMNETPNPMAN.EXE | Siemens |

| SMARTSERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| SSERVCFG.EXE | Siemens |

| TOUCHINPUTPC.EXE | Siemens |

| TRACECONCEPTX.EXE | Siemens |

| TRACESERVER.EXE | Siemens |

| UM.RIS.EXE | Siemens |

| UM.SSO.EXE | Siemens |

| WEBNAVIGATORRT.EXE | Siemens |

| WINCCEXPLORER.EXE | Siemens |

| CCDMRTCHANNELHOST.EXE | Siemens |

| ANSYS.ACT.BROWSER.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYS.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYS192.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYSFWW.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYSLI_CLIENT.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYSLI_MONITOR.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYSLI_SERVER.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYSLMD.EXE | Ansys |

| ANSYSWBU.EXE | Ansys |

| CONFIGSERVERI64.EXE | Tani |

| ENGINELOGGERI64.EXE | Tani |

| PLCENGINEI64.EXE | Tani |