SCANdalous! (External Detection Using Network Scan Data and Automation)

Real Quick

In case you’re thrown by that fantastic title, our lawyers made us change the name of this project so we wouldn’t get sued. SCANdalous—a.k.a. Scannah Montana a.k.a. Scanny McScanface a.k.a. “Scan I Kick It? (Yes You Scan)”—had another name before today that, for legal reasons, we’re keeping to ourselves. A special thanks to our legal team who is always looking out for us, this blog post would be a lot less fun without them. Strap in folks.

Introduction

Advanced Practices is known for using primary source data obtained through Mandiant Incident Response, Managed Defense, and product telemetry across thousands of FireEye clients. Regular, first-hand observations of threat actors afford us opportunities to learn intimate details of their modus operandi. While our visibility from organic data is vast, we also derive value from third-party data sources. By looking outwards, we extend our visibility beyond our clients’ environments and shorten the time it takes to detect adversaries in the wild—often before they initiate intrusions against our clients.

In October 2019, Aaron Stephens gave his “Scan’t Touch This” talk at the annual FireEye Cyber Defense Summit (slides available on his Github). He discussed using network scan data for external detection and provided examples of how to profile command and control (C2) servers for various post-exploitation frameworks used by criminal and intelligence organizations alike. However, manual application of those techniques doesn’t scale. It may work if your role focuses on one or two groups, but Advanced Practices’ scope is much broader. We needed a solution that would enable us to track thousands of groups, malware families and profiles. In this blog post we’d like to talk about that journey, highlight some wins, and for the first time publicly, introduce the project behind it all: SCANdalous.

Pre-SCANdalous Case Studies

Prior to any sort of system or automation, our team used traditional profiling methodologies to manually identify servers of interest. The following are some examples. The success we found in these case studies served as the primary motivation for SCANdalous.

APT39 SSH Tunneling

After observing APT39 in a series of intrusions, we determined they frequently created Secure Shell (SSH) tunnels with PuTTY Link to forward Remote Desktop Protocol connections to internal hosts within the target environment. Additionally, they preferred using BitVise SSH servers listening on port 443. Finally, they were using servers hosted by WorldStream B.V.

Independent isolation of any one of these characteristics would produce a lot of unrelated servers; however, the aggregation of characteristics provided a strong signal for newly established infrastructure of interest. We used this established profile and others to illuminate dozens of servers we later attributed to APT39, often before they were used against a target.

APT34 QUADAGENT

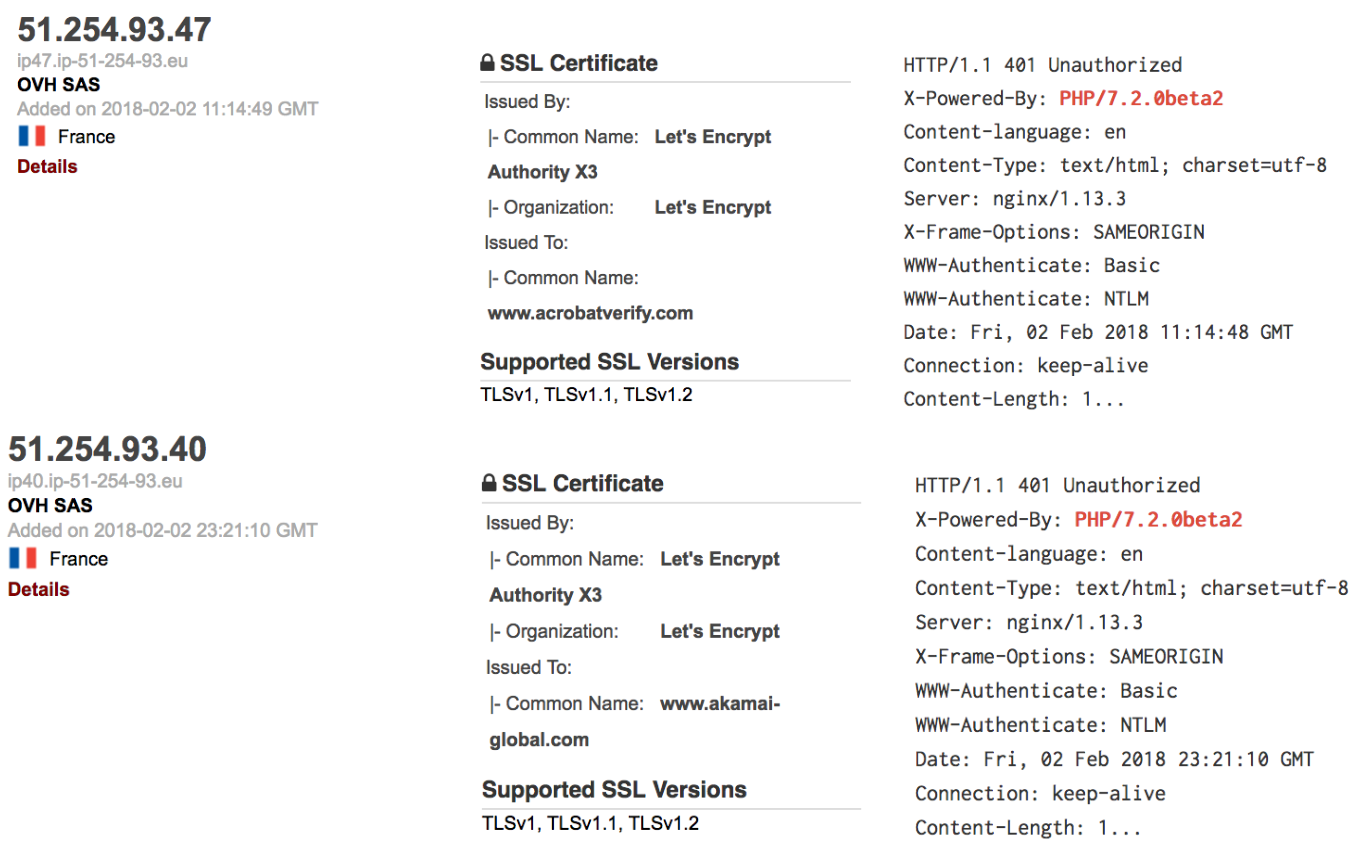

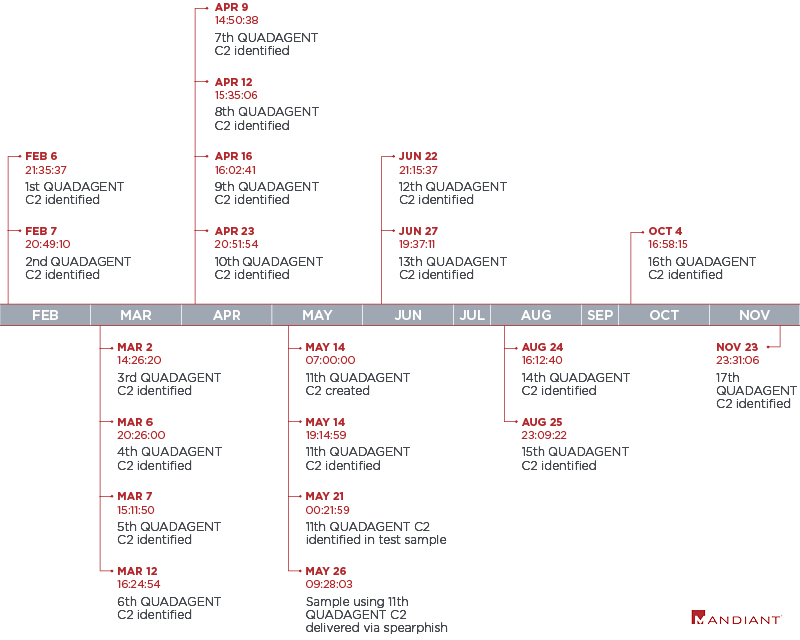

In February 2018, an independent researcher shared a sample of what would later be named QUADAGENT. We had not observed it in an intrusion yet; however, by analyzing the characteristics of the C2, we were able to develop a strong profile of the servers to track over time. For example, our team identified the server 185.161.208\.37 and domain rdppath\.com within hours of it being established. A week later, we identified a QUADAGENT dropper with the previously identified C2. Additional examples of QUADAGENT are depicted in Figure 1.

Five days after the QUADAGENT dropper was identified, Mandiant was engaged by a victim that was targeted via the same C2. This activity was later attributed to APT34. During the investigation, Mandiant uncovered APT34 using RULER.HOMEPAGE. This was the first time our consultants observed the tool and technique used in the wild by a real threat actor. Our team developed a profile of servers hosting HOMEPAGE payloads and began tracking their deployment in the wild. Figure 2 shows a timeline of QUADAGENT C2 servers discovered between February and November of 2018.

APT33 RULER.HOMEPAGE, POSHC2, and POWERTON

A month after that aforementioned intrusion, Managed Defense discovered a threat actor using RULER.HOMEPAGE to download and execute POSHC2. All the RULER.HOMEPAGE servers were previously identified due to our efforts. Our team developed a profile for POSHC2 and began tracking their deployment in the wild. The threat actor pivoted to a novel PowerShell backdoor, POWERTON. Our team repeated our workflow and began illuminating those C2 servers as well. This activity was later attributed to APT33 and was documented in our OVERRULED post.

SCANdalous

Scanner, Better, Faster, Stronger

Our use of scan data was proving wildly successful, and we wanted to use more of it, but we needed to innovate. How could we leverage this dataset and methodology to track not one or two, but dozens of active groups that we observe across our solutions and services? Even if every member of Advanced Practices was dedicated to external detection, we would still not have enough time or resources to keep up with the amount of manual work required. But that’s the key word: Manual. Our workflow consumed hours of individual analyst actions, and we had to change that. This was the beginning of SCANdalous: An automated system for external detection using third-party network scan data.

A couple of nice things about computers: They’re great at multitasking, and they don’t forget. The tasks that were taking us hours to do—if we had time, and if we remembered to do them every day—were now taking SCANdalous minutes if not seconds. This not only afforded us additional time for analysis, it gave us the capability to expand our scope. Now we not only look for specific groups, we also search for common malware, tools and frameworks in general. We deploy weak signals (or broad signatures) for software that isn’t inherently bad, but is often used by threat actors.

Our external detection was further improved by automating additional collection tasks, executed by SCANdalous upon a discovery—we call them follow-on actions. For example, if an interesting open directory is identified, acquire certain files. These actions ensure the team never misses an opportunity during “non-working hours.” If SCANdalous finds something interesting on a weekend or holiday, we know it will perform the time-sensitive tasks against the server and in defense of our clients.

The data we collect not only helps us track things we aren’t seeing at our clients, it allows us to provide timely and historical context to our incident responders and security analysts. Taking observations from Mandiant Incident Response or Managed Defense and distilling them into knowledge we can carry forward has always been our bread and butter. Now, with SCANdalous in the mix, we can project that knowledge out onto the Internet as a whole.

Collection Metrics

Looking back on where we started with our manual efforts, we’re pleased to see how far this project has come, and is perhaps best illustrated by examining the numbers. Today (and as we write these continue to grow), SCANdalous holds over five thousand signatures across multiple sources, covering dozens of named malware families and threat groups. Since its inception, SCANdalous has produced over two million hits. Every single one of those, a piece of contextualized data that helps our team make analytical decisions. Of course, raw volume isn’t everything, so let’s dive a little deeper.

When an analyst discovers that an IP address has been used by an adversary against a named organization, they denote that usage in our knowledge store. While the time at which this observation occurs does not always correlate with when it was used in an intrusion, knowing when we became aware of that use is still valuable. We can cross-reference these times with data from SCANdalous to help us understand the impact of our external detection.

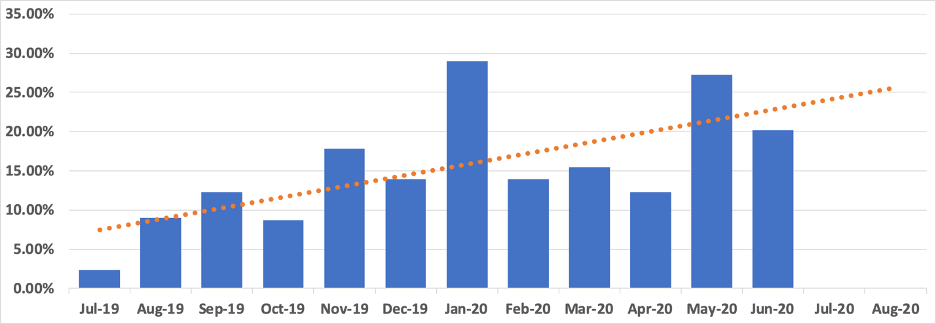

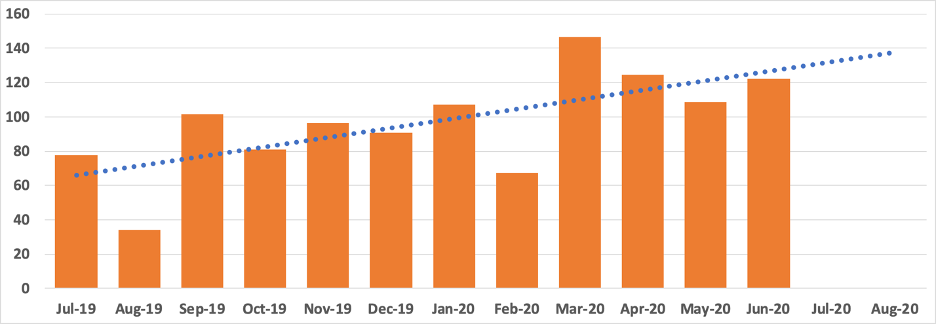

Looking at the IP addresses marked by an analyst as observed at a client in the last year, we find that 21.7% (more than one in five) were also found by SCANdalous. Of that fifth, SCANdalous has an average lead time of 47 days. If we only consider the IP addresses that SCANdalous found first, the average lead time jumps to 106 days. Going even deeper and examining this data month-to-month, we find a steady upward trend in the percentage of IP addresses identified by SCANdalous before being observed at a client (Figure 3).

A similar pattern can be seen for SCANdalous’ average lead time over the same data (Figure 4).

As we continue to create signatures and increase our external detection efforts, we can see from these numbers that the effectiveness and value of the resulting data grow as well.

SCANdalous Case Studies

Today in Advanced Practices, SCANdalous is a core element of our external detection work. It has provided us with a new lens through which we can observe threat activity on a scale and scope beyond our organic data, and enriches our workflows in support of Mandiant. Here are a few of our favorite examples:

FIN6

In early 2019, SCANdalous identified a Cobalt Strike C2 server that we were able to associate with FIN6. Four hours later, the server was used to target a Managed Defense client, as discussed in our blog post, Pick-Six: Intercepting a FIN6 Intrusion, an Actor Recently Tied to Ryuk and LockerGoga Ransomware.

FIN7

In late 2019, SCANdalous identified a BOOSTWRITE C2 server and automatically acquired keying material that was later used to decrypt files found in a FIN7 intrusion worked by Mandiant consultants, as discussed in our blog post, Mahalo FIN7: Responding to the Criminal Operators’ New Tools and Techniques.

UNC1878 (financially motivated)

Some of you may also remember our recent blog post on UNC1878. It serves as a great case study for how we grow an initial observation into a larger set of data, and then use that knowledge to find more activity across our offerings. Much of the early work that went into tracking that activity (see the section titled “Expansion”) happened via SCANdalous. The quick response from Managed Defense gave us just enough information to build a profile of the C2 and let our automated system take it from there. Over the next couple months, SCANdalous identified numerous servers matching UNC1878’s profile. This allowed us to not only analyze and attribute new network infrastructure, it also helped us observe when and how they were changing their operations over time.

Conclusion

There are hundreds more stories to tell, but the point is the same. When we find value in an analytical workflow, we ask ourselves how we can do it better and faster. The automation we build into our tools allows us to not only accomplish more of the work we were doing manually, it enables us to work on things we never could before. Of course, the conversion doesn’t happen all at once. Like all good things, we made a lot of incremental improvements over time to get where we are today, and we’re still finding ways to make more. Continuing to innovate is how we keep moving forward – as Advanced Practices, as FireEye, and as an industry.

Example Signatures

The following are example Shodan queries; however, any source of scan data can be used.

Used to Identify APT39 C2 Servers

- product:“bitvise” port:“443” org:“WorldStream B.V.”

Used to Identify QUADAGENT C2 Servers

- “PHP/7.2.0beta2”

RULER.HOMEPAGE Payloads

- html:“clsid:0006F063-0000-0000-C000-000000000046”