FLOSS for Gophers and Crabs: Extracting Strings from Go and Rust Executables

![]() The evolving landscape of software development has introduced new programming languages like Go and Rust. Binaries compiled from these languages work differently to classic (C/C++) programs and challenge many conventional analysis tools. To support the static analysis of Go and Rust executables, FLOSS now extracts program strings using enhanced algorithms. Where traditional extraction algorithms provide compound and confusing string output FLOSS recovers the individual Go and Rust strings as they are used in a program.

The evolving landscape of software development has introduced new programming languages like Go and Rust. Binaries compiled from these languages work differently to classic (C/C++) programs and challenge many conventional analysis tools. To support the static analysis of Go and Rust executables, FLOSS now extracts program strings using enhanced algorithms. Where traditional extraction algorithms provide compound and confusing string output FLOSS recovers the individual Go and Rust strings as they are used in a program.

To start using FLOSS download one of the standalone binaries from our releases page, install the tool from PyPI, or from source code. To learn more about FLOSS’ background and additional functionality please review the version 1 and version 2 blog posts.

The enhanced Go and Rust string extraction was implemented by Arnav Kharbanda (@Arker123) as part of a Google Summer of Code project that the Mandiant FLARE team mentored in 2023. To learn more about the program and our open-source contributors check out the introductory post.

Motivation

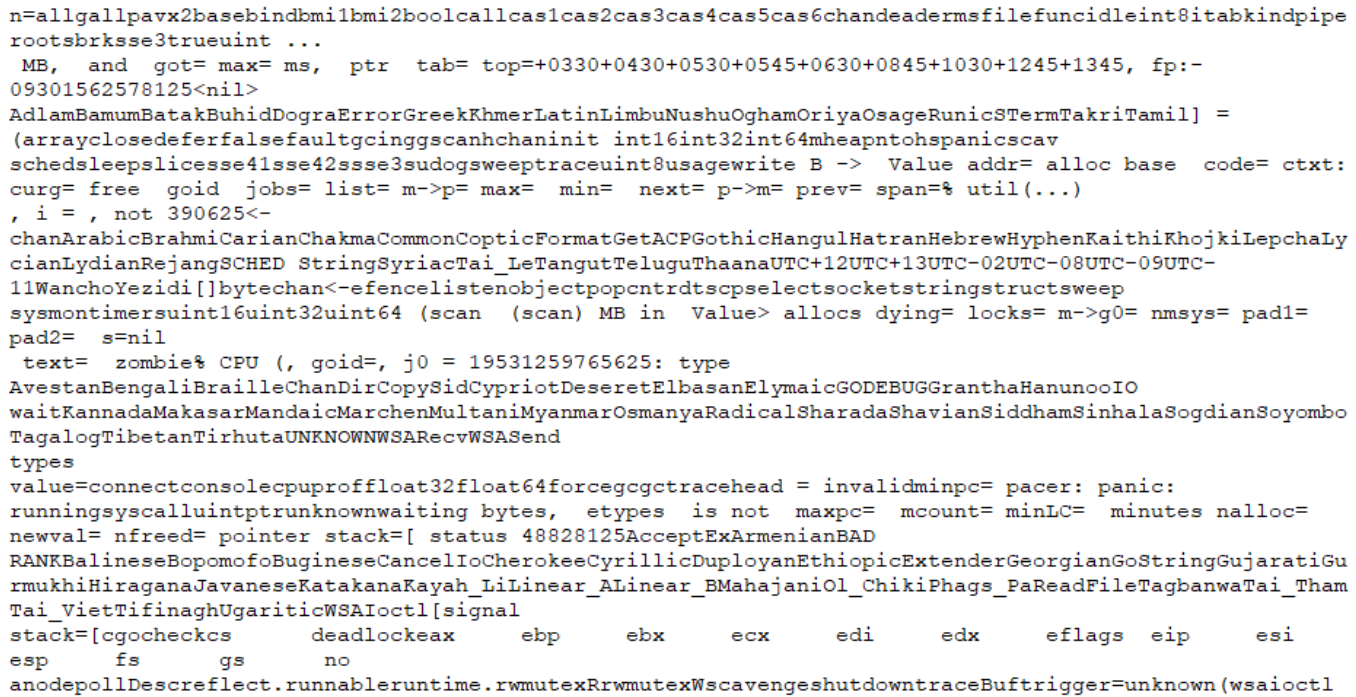

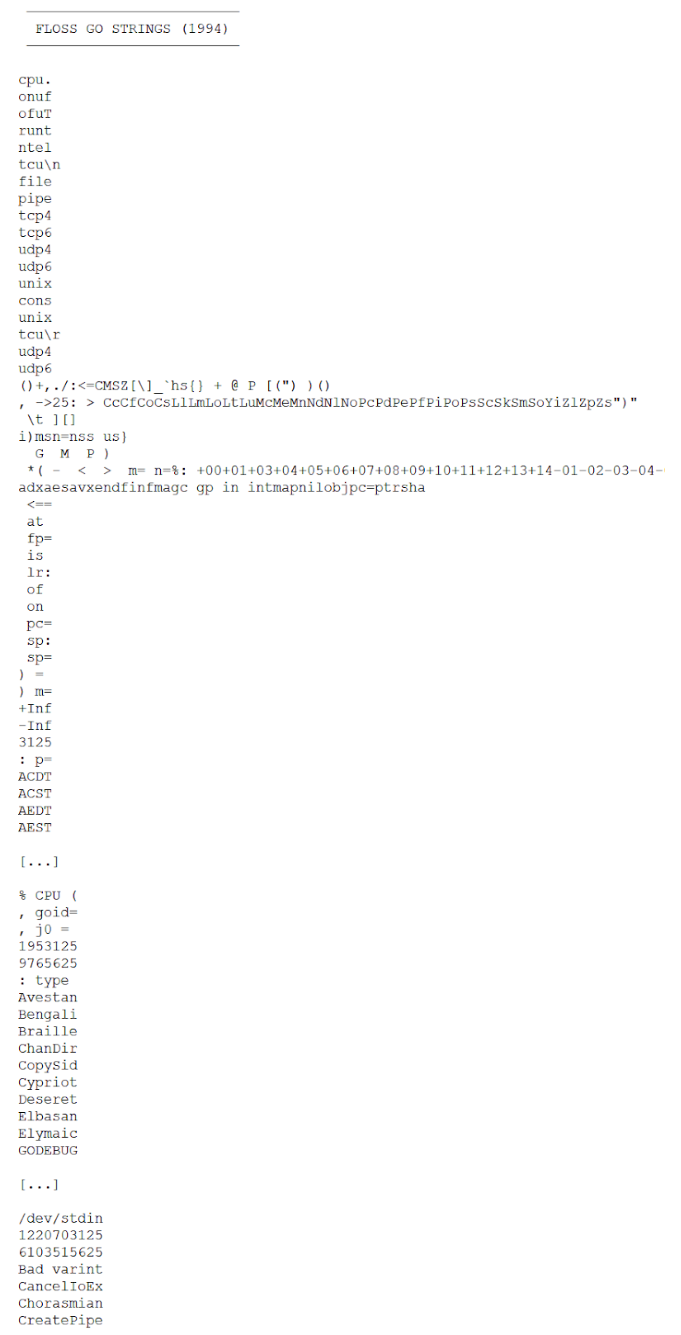

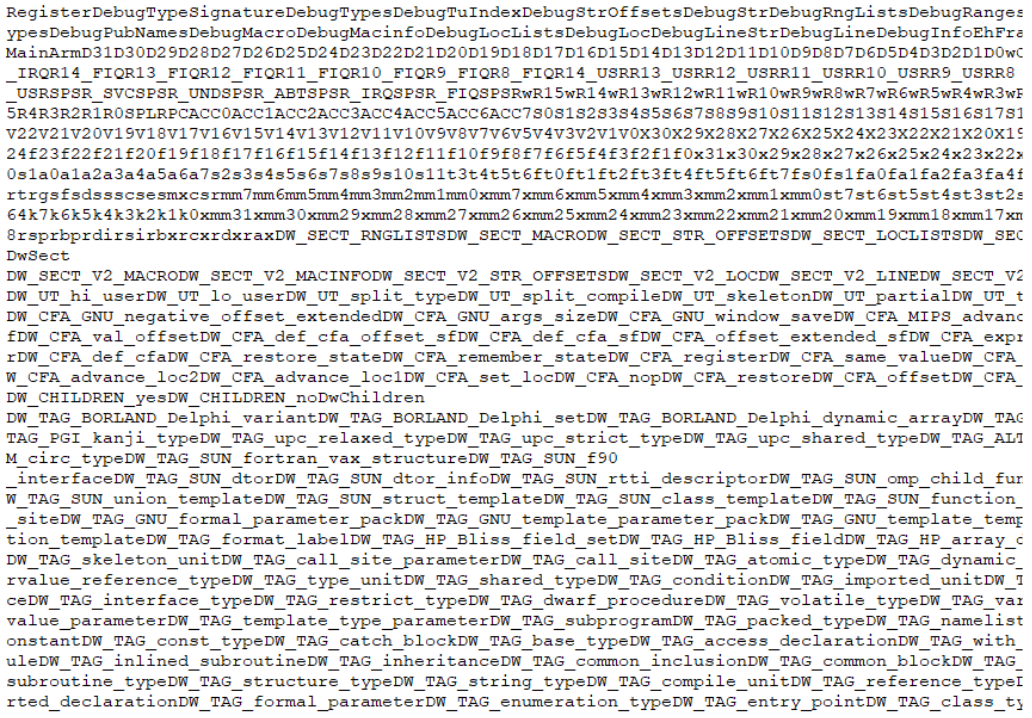

Analysts who have inspected Go or Rust samples know how confusing the traditional strings.exe output is for these samples. At first glance everything seems to be as usual but then you encounter a region where hundreds of strings are compounded together as shown in Figure 1. With this output it is very hard to gain the initial understanding of an unknown program that file strings can normally provide.

This problem arises because Rust and Go compilers do not NULL-terminate strings. Instead, they use structures to store string offsets and lengths. This representation breaks traditional string extraction algorithms to find printable character sequences of a certain length terminated by one or two NULL bytes.

Using FLOSS to extract Go and Rust strings

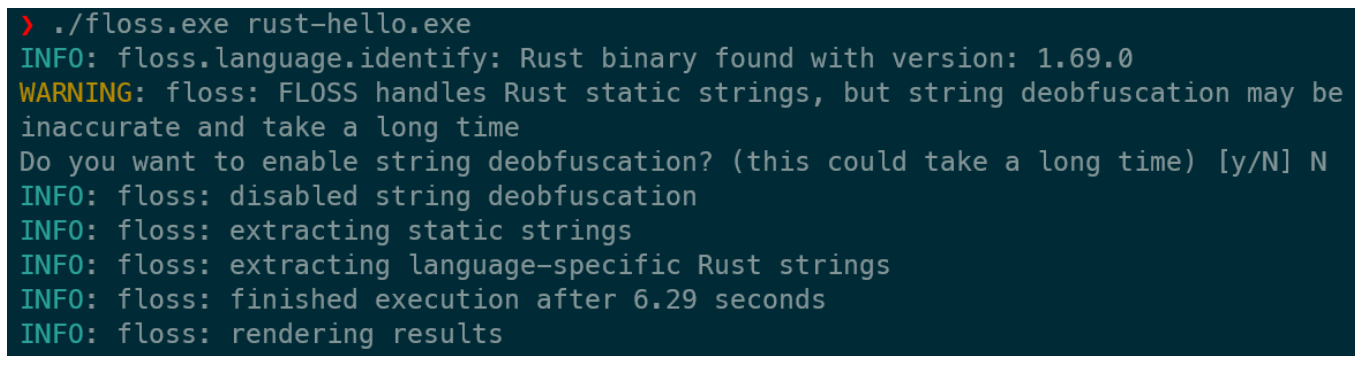

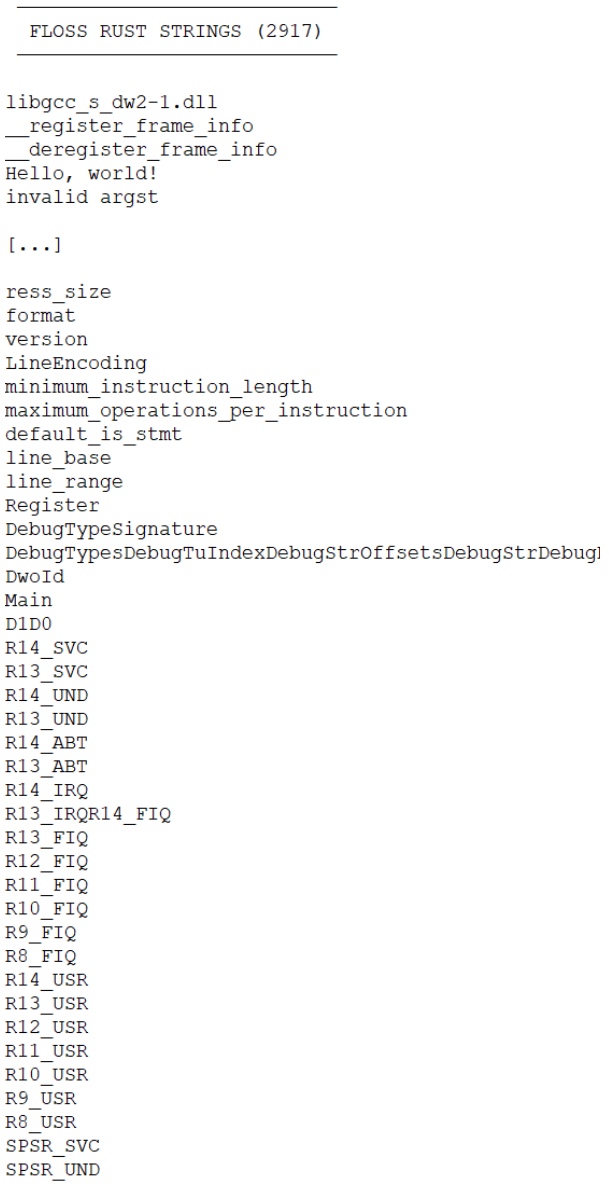

Figure 2 shows an example of running FLOSS version 3.0 on a Rust executable. When detecting a supported compiler (rustc version 1.69.0 in this example) FLOSS applies its special logic to extract and render strings. Currently, the algorithms are specific to Windows PE files, but we hope to support more executable formats after some additional research.

By default FLOSS extracts multiple string types. This includes strings recovered using the traditional strings.exe and via its custom deobfuscation algorithms. However, string deobfuscation may be inaccurate or take a long time for Go and Rust executables because they are often large and have many and/or complex functions to analyze.

To only focus on the static strings of Go and Rust programs you can use the --only/--no arguments to enable or disable the extraction of a string type, e.g., static or decoded. See our usage documentation for more information on all the available options.

Go and Rust strings are part of the static string extraction. The language-specific strings are listed in a section named FLOSS GO STRINGS or FLOSS RUST STRINGS. This section follows the output of the regular ASCII and UTF16-LE encoded strings.

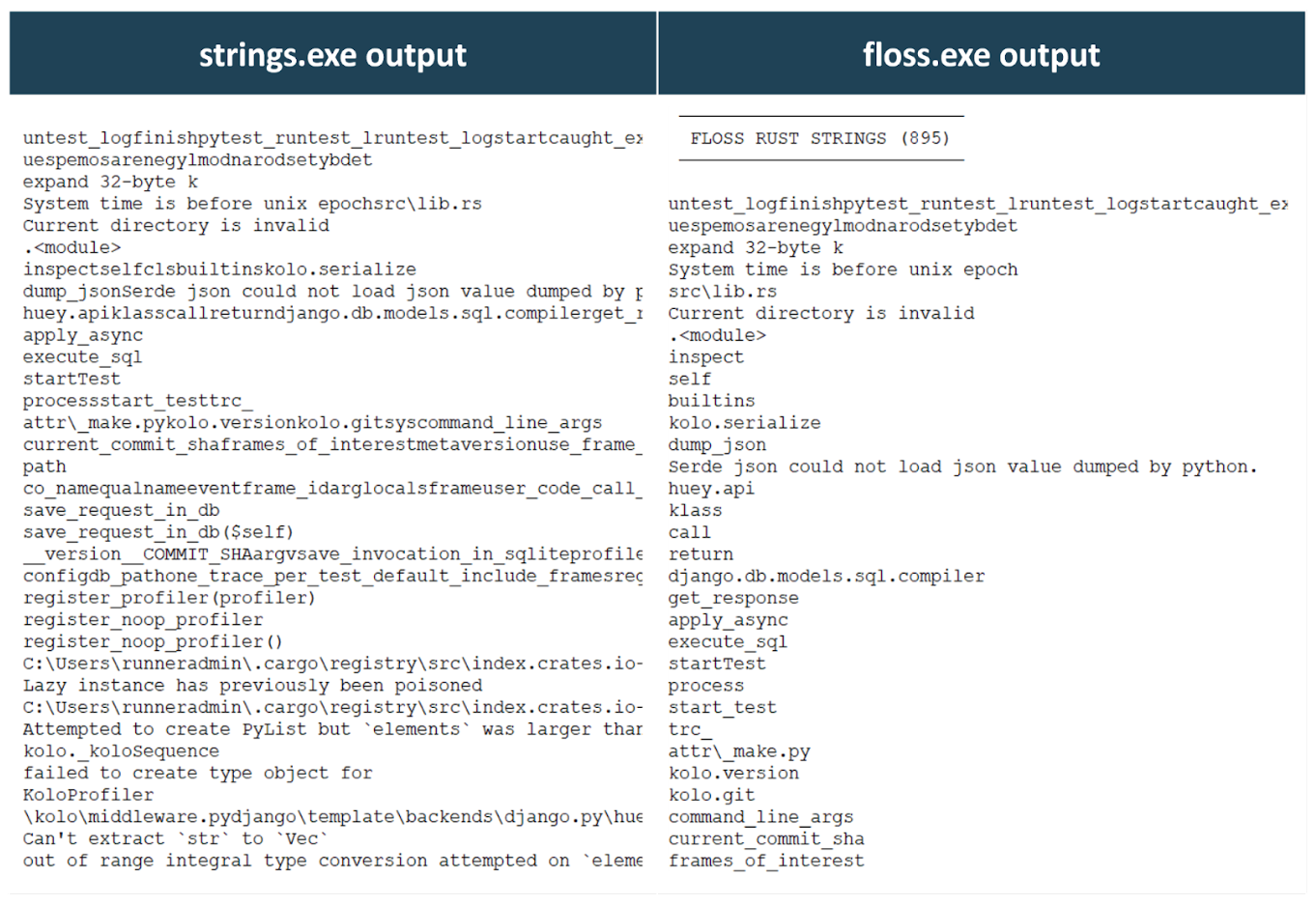

Figure 3 compares the strings.exe output to the FLOSS extraction results. FLOSS separates the compound strings and makes it much easier to find interesting character sequences and gain an initial understanding of the program.

Identifying programs written in Go and Rust

FLOSS uses byte and character sequences to identify the underlying program compiler. To recognize Go programs the tool tries to identify magic header values in the pclntab header structure. If this fails (common for obfuscated binaries with stomped magics), the tool searches for Go function name strings vital to the statically linked runtime. For additional details please see this Go internals and symbol recovery blog post.

To identify Rust compilers FLOSS searches common Rust string patterns, including those related to error handling (via the panic! macro). We have created a database to recover the compiler version from these patterns.

Although the string extraction algorithms described later in this post are identical for all compiler versions (each language uses one generic approach to extract strings) identifying the version may help us to uncover improvement possibilities. Older or very new compiler versions may require code updates, for example. If you encounter any issues, including failed, incorrect, or incomplete extractions, please contact us and include the detected compiler version and, if you can share it, the sample.

If Go or Rust identification fails altogether, you can manually select a language using the --language argument. To enforce the extraction of Rust strings, for example, run: floss.exe --language rust rusty_ferris.exe.

Extracting Strings from Go Binaries

Go strings are generally UTF-8 encoded, however, this isn’t guaranteed. In compiled (modern) Go binaries the most interesting strings for analysts are commonly stored without a NULL terminator. Instead, the program encodes the string lengths using internal structures or directly in the code. In programs generated by older compilers you may find NULL terminated strings. These are recoverable using traditional string identification algorithms and not further covered here.

Go String Representation in Binaries

To extract Go strings we need to understand how binaries store and access them. Our algorithms focus on various storage and access patterns. The first pattern uses a String structure (shown in Figure 4) that stores a pointer to the string and its length.

|

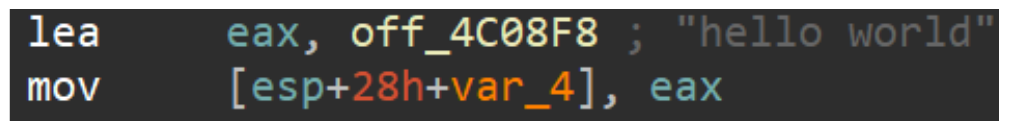

The disassembled Go program in Figure 5 shows how code may reference this structure.

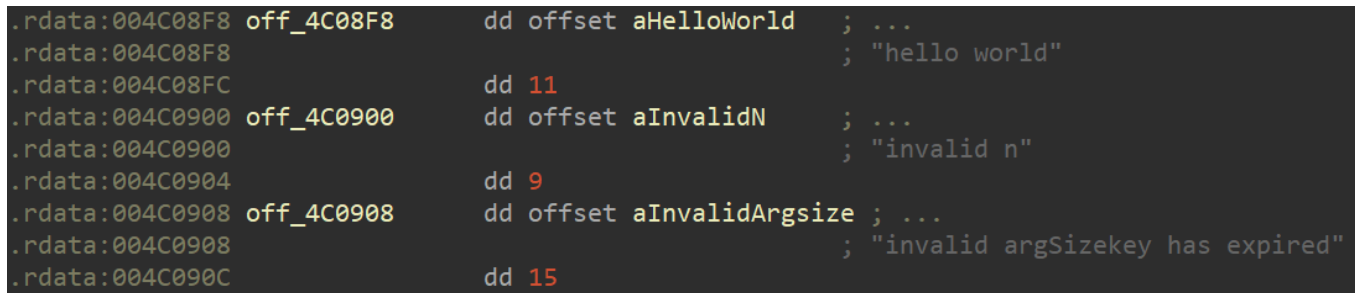

Figure 6 shows the referenced (“hello world”) String structure and two additional structures. Each structure consists of a pointer to the string bytes and the associated string length. In Windows PE files String structures and the actual character bytes are typically stored in the .rdata or .data section.

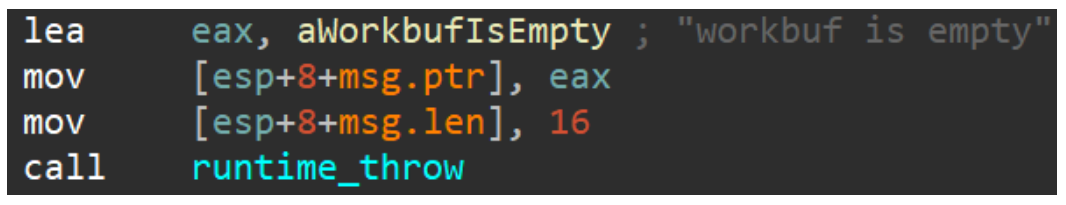

Figure 7 shows an example of the second access pattern where the program instructions directly contain the string pointer and length. Here the string is dynamically created on the stack using the same underlying String structure fields.

Extracting Go Strings from Windows PE files

FLOSS identifies String structures and code references in Go programs to extract individual strings with corresponding lengths. We created an algorithm to do this efficiently over the file bytes without the need to disassemble the program or perform other advanced time-consuming analysis steps.

Our algorithm relies on the Go linker storing strings in one consecutive range in length-sorted order, from shortest to longest (see the collection of symbols into groups and the sorting in the source). To find this range the algorithm first searches the program data for all String structure candidates. We then find the longest run of monotonically increasing candidate string lengths. The longest run helps us locate the string range without needing to read all candidate string data. So, we save hundreds of thousands of read operations which could take many minutes. From the mid string of the identified range the algorithm searches for surrounding end markers having four zero bytes to find the lower and upper boundaries. We use four zero bytes to handle binaries that embed non-UTF-8 sequences of bytes, including two zero bytes. Finally, we split the string data within the boundaries into individual strings as indicated by the string candidate pointers.

Figure 8 shows how almost 2000 Go strings are extracted from a program. Starting with the 4-character string “ <==“ the output lists the Go strings as they are stored in the file (sorted by length and then alphabetically). Four characters is FLOSS’ minimum default length but this can be configured using the -n/--minimum-length argument.

Extracting Strings from Rust Binaries

Strings in Rust (String and str) are guaranteed to be valid UTF-8 sequences. FLOSS focuses on these and doesn't specifically handle other string types which may contain non-UTF-8 characters such as OsStrings or byte strings (arrays of bytes). Similar to Go, strings in compiled Rust binaries are not stored with a NULL terminator. Instead, program instructions and internal structures encode lengths when using strings at runtime.

Figure 9 shows the output of strings.exe with many compound strings for a Rust sample.

Rust String Representation in Binaries

For Windows PE files Rust strings commonly reside in the binary's .rdata section. Similar to Go various storage and access patterns exist. Figure 10 shows a C-style structure of the Rust str primitive.

|

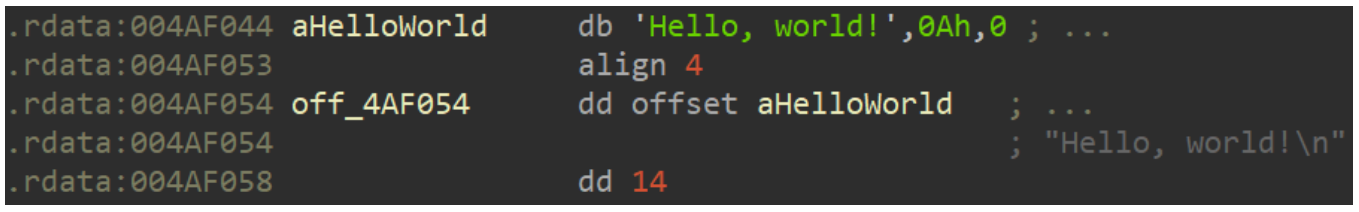

The disassembly in Figure 11 shows a structure storing a pointer to the character bytes and a length, and also shows the character bytes just above the structure.

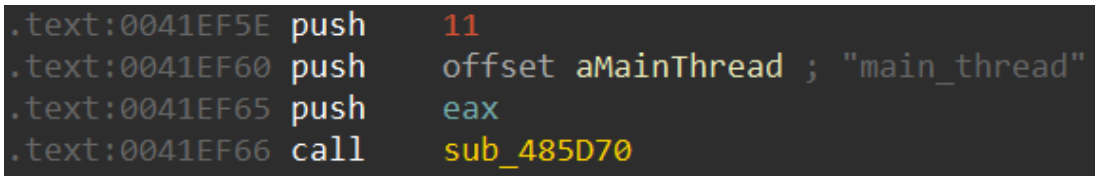

Analogous to the aforementioned Go example, Figure 12 shows a second string usage pattern where a string structure is pushed onto the stack. In the example the string is passed as a function argument using two pushes (string length and pointer to the string bytes) followed by another argument stored in eax.

Extracting Rust Strings from Windows PE files

To extract strings from programs created using the Rust compiler, FLOSS reuses many of the ideas and functions used for the Go string extraction. Similarly, extraction is currently limited to Windows PE files, but we anticipate that adding support for other executable formats is fairly straightforward.

In Rust binaries string symbols are not stored in a particular order that we can leverage for our extraction. As an approximation our algorithm instead finds all UTF-8 encoded string data from the binary’s .rdata section. FLOSS then searches the program’s data and code segments for string storage and usage patterns. We scan the binary data sections for patterns that look similar to the Rust str structure layout (as seen in Figure 11). We additionally scan the assembly to locate common mnemonics that reference string pointers, such as LEA, PUSH, and MOV (as seen in Figure 12). The derived string boundaries are then used to split the initially found UTF-8 encoded data into individual strings.

Figure 13 shows the results of running FLOSS on a Rust PE file. The tool extracts almost 3,000 Rust-specific strings which makes it easier for analysts to gain a basic understanding of the program.

Conclusion

The newest release of FLOSS extracts strings from Windows binaries written in Go and Rust. We hope this functionality supports analysts when triaging unknown programs. If you have any feedback or encounter issues using the tool please contact us via the FLOSS GitHub page. We’re looking forward to working with the community to improve the extraction algorithms and support additional file formats.

To try out FLOSS’ new functionality download a standalone binary from the Release page or use pip to install the tool from PyPI. You can then run the tool against any Windows PE Go or Rust sample to extract language-specific strings. Please refer to our documentation with more details on how to install and use FLOSS.