The GRU's Disruptive Playbook

Key Judgments

- Since last February's invasion, Mandiant has tracked Russian military intelligence (GRU) disruptive operations against Ukraine adhering to a standard five-phase playbook.

- Mandiant assesses with moderate confidence that this standard concept of operations represents a deliberate effort to increase the speed, scale, and intensity at which the GRU can conduct offensive cyber operations, while minimizing the odds of detection.

- The tactical and strategic benefits the playbook affords are likely tailored for a fast-paced and highly contested operating environment. We judge this operational approach may be mirrored in future crises and conflict scenarios where requirements to support high volumes of disruptive cyber operations are present.

Summary

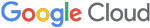

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine with troops massed on the border of the two countries that had been building since the previous fall. As Mandiant has detailed previously in reports such as M-Trends 2023 and other resources available in our Ukraine Crisis Resource Center, we have tracked Russian cyber operations against Ukraine both leading up to and following the invasion. We categorize these operations stretching back before the start of the war on February 24, 2022, into six phases, spanning access operations, cyber espionage, waves of disruptive attacks, and information operations.

Although there has been a significant focus on the sheer volume of wiper activity and the perception of “success” of these disruptive operations, there is more to the story of Russian military intelligence (GRU) disruptive operations than just wipers. We have observed the same five components being executed across the disruptive operations in Ukraine, combining the GRU’s cyber and information operations into a unified wartime capability. To equip defenders with knowledge of this standard operational approach, we have outlined the GRU’s disruptive playbook, which expands on the patterns of tactical and strategic behavior Mandiant has observed. To demonstrate the playbook in action, we examine a UNC3810 operation targeting a Ukrainian government entity with CADDYWIPER that took place in the fifth phase of the war, a renewed campaign of disruptive attacks at the end of 2022.

Overview: The GRU’s Disruptive Playbook

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Mandiant Intelligence has observed the GRU operate a standard, repeatable playbook to pursue its information confrontation objectives. The persistent use of this playbook through the six phases of Russia’s war has indicated its high adaptability across a range of different operational contexts, targets, and over 15 different destructive malware variants. The playbook has also proved highly survivable and resilient to detection and technical countermeasures, allowing the GRU to adhere to a common set of tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) despite an extended period of aggressive, high tempo operational use. Mandiant has observed the playbook in use by multiple distinct Russian threat clusters throughout the war, indicating its central role in standardizing operations across multiple subteams in an attempt to deliver more repeatable, consistent effects.

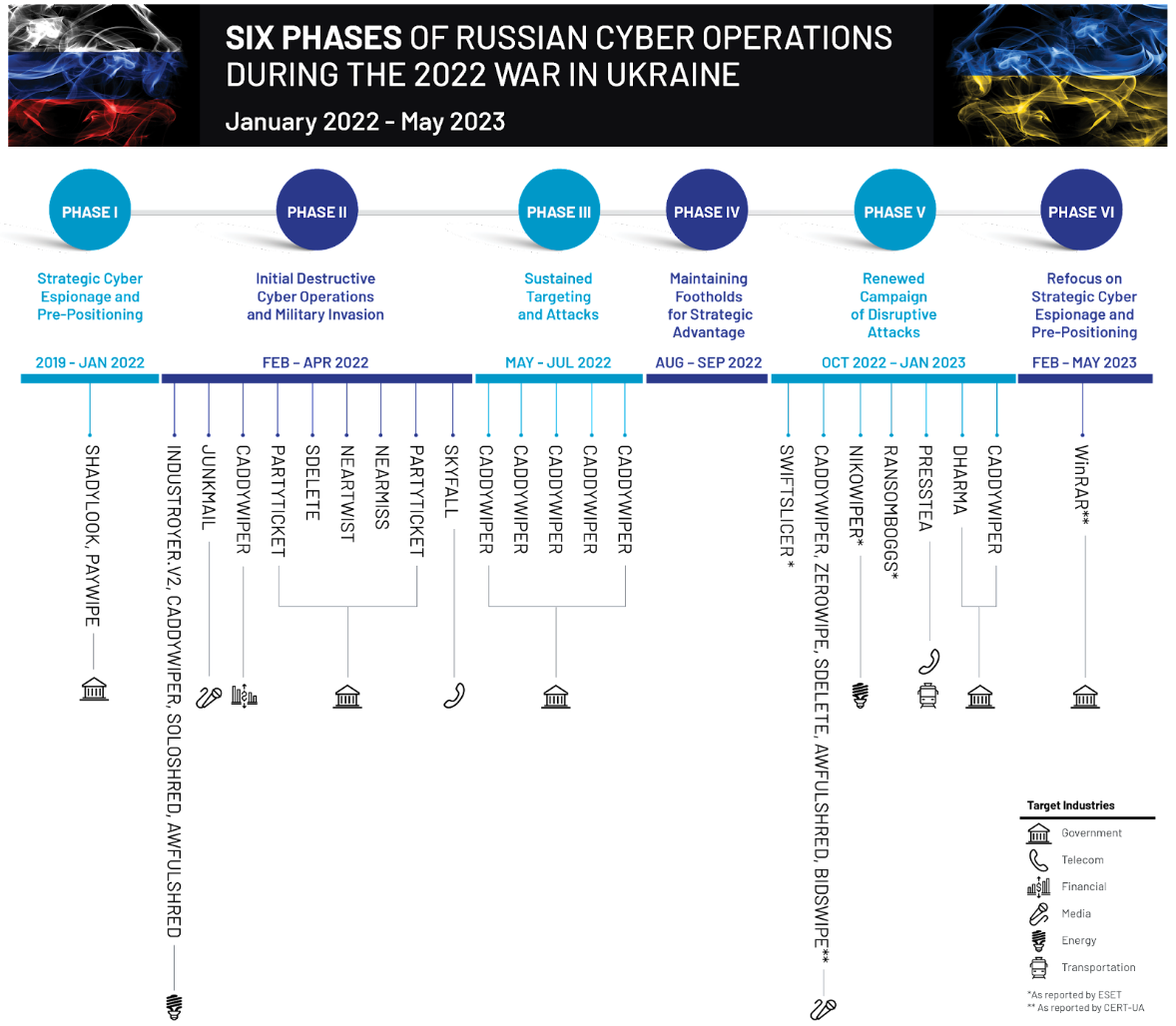

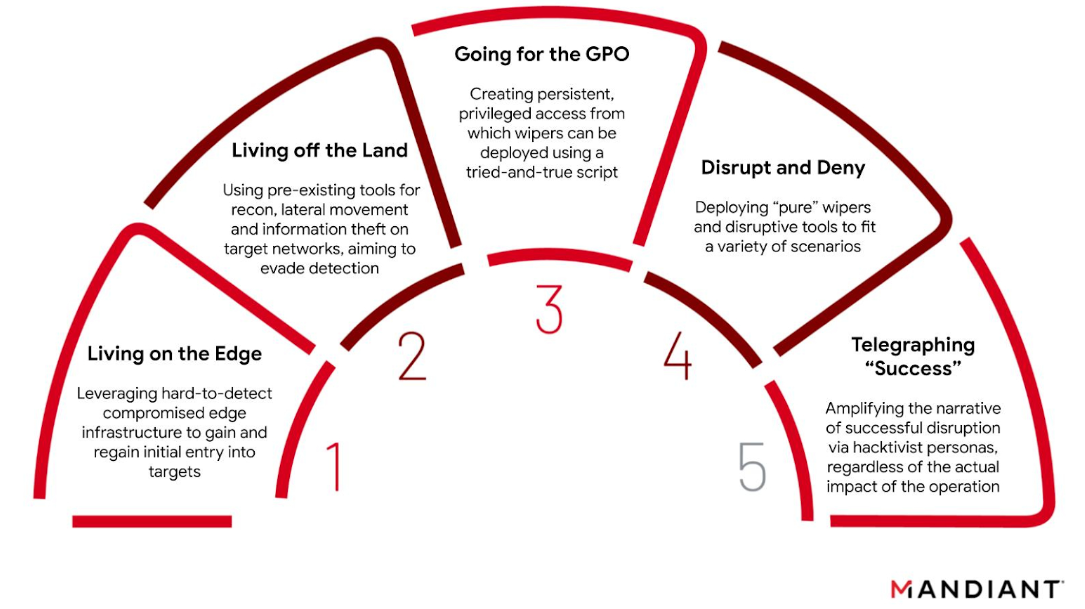

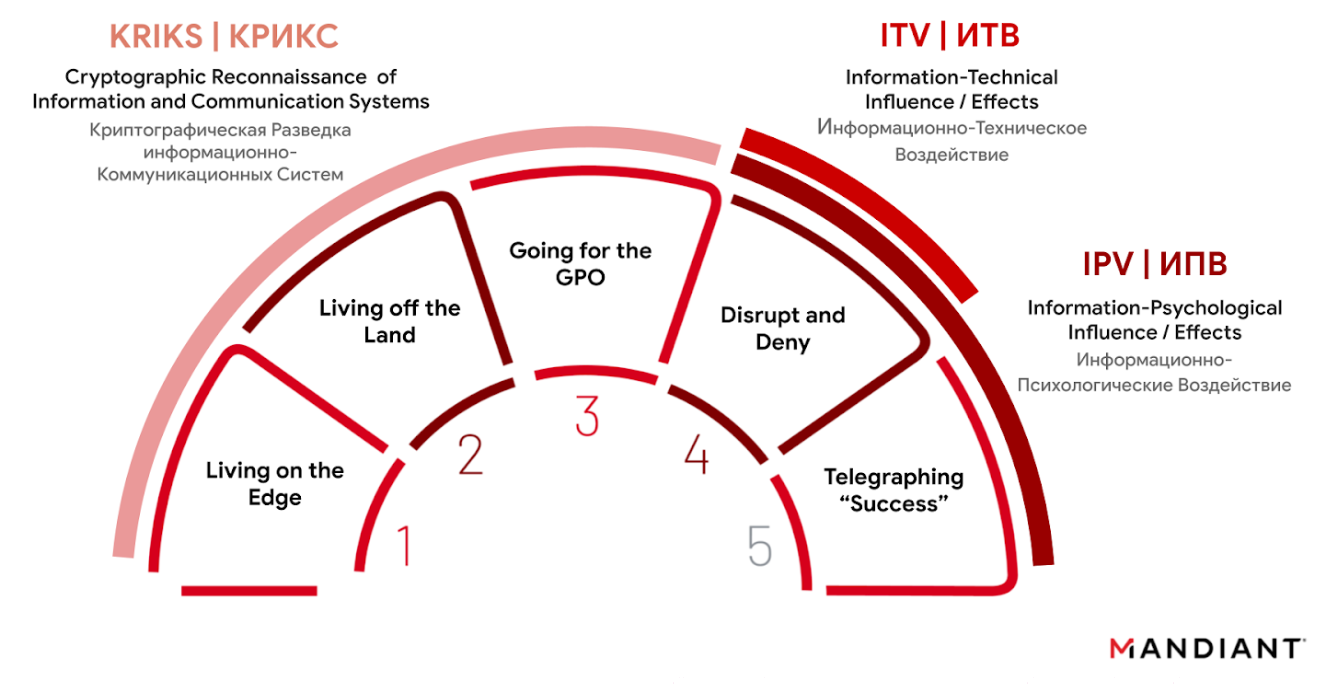

Across the incidents Mandiant has responded to, we have seen suspected GRU threat clusters generally adhere to the following five operational phases:

- Living on the Edge: Leveraging hard-to-detect compromised edge infrastructure such as routers, VPNs, firewalls, and mail servers to gain and regain initial access into targets.

- Living off the Land: Using built-in tools such as operating system components or pre-installed software for reconnaissance, lateral movement and information theft on target networks, likely aiming to limit their malware footprint and evade detection.

- Going for the GPO: Creating persistent, privileged access from which wipers can be deployed via group policy objects (GPO) using a tried-and-true PowerShell script.

- Disrupt and Deny: Deploying “pure” wipers and other low-equity disruptive tools such as ransomware to fit a variety of contexts and scenarios.

- Telegraphing “Success”: Amplifying the narrative of successful disruption via a series of hacktivist personas on Telegram, regardless of the actual impact of the operation.

Mandiant assesses with moderate confidence that this standard concept of operations highly likely represents a deliberate effort to increase the speed, scale, and intensity at which the GRU could conduct offensive cyber operations while minimizing the odds of detection. The benefits the playbook affords are notably suited for a fast-paced and highly contested operating environment, indicating that Russia’s wartime goals have likely guided the GRU’s chosen tactical courses of action. While other options have existed at each stage of the playbook, the GRU has opted for the same tradecraft repeatedly. We anticipate that similar operational approaches, or “playbooks”, may be mirrored in future crises and conflict scenarios where requirements to support high volumes of disruptive cyber operations are present.

| Phase | Assessed Tactical Benefits | Assessed Strategic Benefits |

| Living on the Edge |

|

|

| Living off the Land |

|

|

| Going for the GPO |

|

|

| Disrupt and Deny |

|

|

| Telegraph “Success” |

|

|

The GRU’s disruptive playbook has sought to integrate the full spectrum of information confrontation (Информационное противоборство) capabilities that Russia conceptually defines as cryptographic reconnaissance of information and communication systems (KRIKS), information-technical effects (ITV), and information-influence effects (IPV). While these concepts generally map to what the threat intelligence community commonly refers to as access operations and their follow-on espionage, attack, and influence missions, it is important to understand how Russia defines these concepts and seeks to incorporate the different components of its cyber program in its own terms. A particular feature of the playbook, and more generally of the GRU's information confrontation over the years, has been its emphasis on the information-psychological effects from its cyber operations, which we judge has driven its overarching focus of its disruptive operations on Ukrainian government and civilian critical infrastructure.

The Playbook in Practice: UNC3810’s Information Confrontation

UNC3810 is one of the primary threat groups that Mandiant has observed executing the GRU’s disruptive playbook in practice. UNC3810 has conducted espionage and disruptive operations against Ukrainian entities since the onset of Russia’s invasion, as well as credential theft operations against a wide variety of global public and private industry organizations. Though UNC3810 has balanced competing priorities of espionage and disruption over the course of the war, this case focuses on the group’s disruptive operations.

Living on the Edge

Russian wartime cyber campaigns in Ukraine have depended on the GRU’s ability to balance priorities for espionage and disruption, thus heavily relying on “living on the edge” of target networks via edge infrastructure. Edge infrastructure is any infrastructure facing the public internet, including firewalls, mail servers, and routers that can be used flexibly for a variety of operational objectives. Edge infrastructure compromise has generally occurred in the early stages of the attack lifecycle, but also takes place later, such as in the case of compromise of internal routers.

In our case study operation, UNC3810 first gained initial access to the target environment in late July 2022, likely via a VPN compromise. After gaining initial access from the edge, UNC3810 accessed several Linux servers and dropped webshell backdoors to establish redundant points of access and further their access to the victim’s network.

Living off the Land

To move off the edge and deeper into target networks, GRU operations have relied upon living off the land tactics, exploiting tools already available in the victim environment such as operating system components and installed software. Commonly used UNC3810 post-compromise utilities include PowerShell, wmiexec, PortProxy, Impacket, and Chisel.

In this specific case, upon establishing a foothold on the Linux servers with an unknown webshell, the operators then attempted to execute GOGETTER, a custom TCP tunneling tool written in Go. UNC3810 timestomped the binary to match modification dates of similarly named binaries in the same directory, an attempt to masquerade as legitimate software. UNC3810 then executed GOGETTER as a scheduled service with a systemd service script.

- /usr/bin/system-sockets

- GOGETTER

- Executed by systemd service

Additionally, UNC3810 likely attempted to modify packet filtering rules, as seen by the attempt at executing iptables-restore. However, the actors misspelled the command as “iptables-restor” several times. The combination of these tools gave the actors persistent access and opportunity for lateral movement across the network environment over a three month period.

Going for the GPO

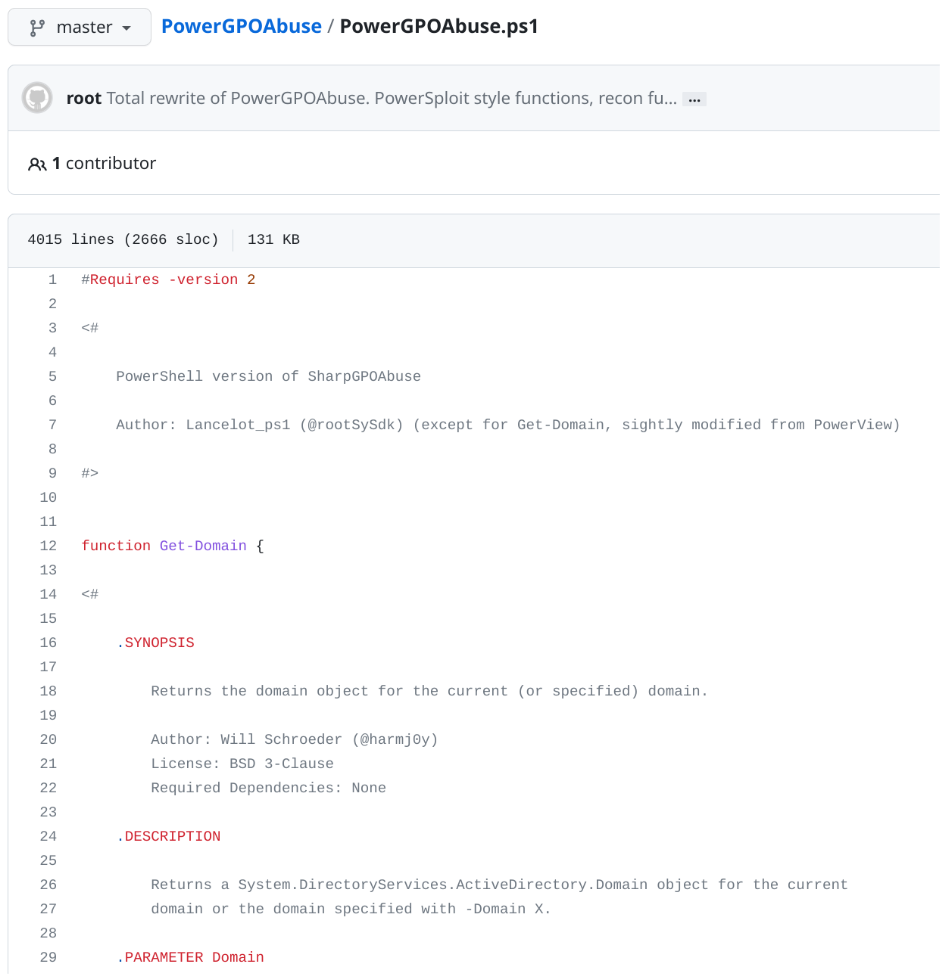

GRU operators manage to persist, escalate privileges, and deploy wipers through TANKTRAP, a script used to create Group Policy Objects (GPOs) to deploy a disruptive payload. GPOs define the settings for the Active Directory environment, which makes GPO abuse particularly powerful. Though GPO addition and/or modification of default GPOs often requires the actor to have the highest level of permissions, it may allow an actor to download additional files and create services and scheduled tasks which will be executed across all Active Directory domain-linked systems.

In the case of UNC3810’s October intrusion, the actor changed default GPOs to deploy CADDYWIPER on all systems joined to the Active Directory domains of the target network. To do so, UNC3810 likely leveraged TANKTRAP, a modified PowerShell utility found on Github called PowerGPOAbuse. TANKTRAP is a staple in the GRU’s disruptive playbook, and has been used by UNC3810 to deliver and execute a variety of different disruptive tools across its operations via GPO.

Upon execution, TANKTRAP creates two group policy preference files:

- Files.xml

- Retrieves CADDYWIPER from the domain controller

- Scheduledtasks.xml

- Creates a scheduled task to execute CADDYWIPER

UNC3810 modified GPOs to launch a scheduled task across the domain which would execute CADDYWIPER for a disruptive effect.

Disrupt and Deny

GRU operations on a targeted host machine frequently end with the deployment of wipers or other disruptive tooling. These disruptive operations hold the potential to cause immediate impact to targeted organizations and sometimes erase evidence of attacker presence.

CADDYWIPER is a wiper that Mandiant first identified and reported on in March 2022, and has become the GRU’s most frequently deployed disruptive tool in Ukraine that we have observed. The malware enumerates the file system's physical drives and overwrites both file content and partitions with null bytes. CADDYWIPER has also notably been deployed alongside other disruptive tools, such as INDUSTROYER.V2, indicating the wiper’s perceived versatility to its operators.

Mandiant and others, including Microsoft, ESET, and CERT UA, have identified multiple variants of CADDYWIPER over time, including x64, x86, and shellcode variants. The GRU has continuously refined CADDYWIPER since its first use in March 2022, iteratively making the wiper more lightweight and flexible, though we continue to see operator error in the malware's deployment. Though these changes may have been necessary tactical evolutions to avoid detection and containment by antivirus products, it is possible they reflect non-tactical considerations as well, such as resource and personnel shortfalls, more direct access to CADDYWIPER's codebase (as evidenced by compile times close to operational use), or top-down pressures to speed up operations.

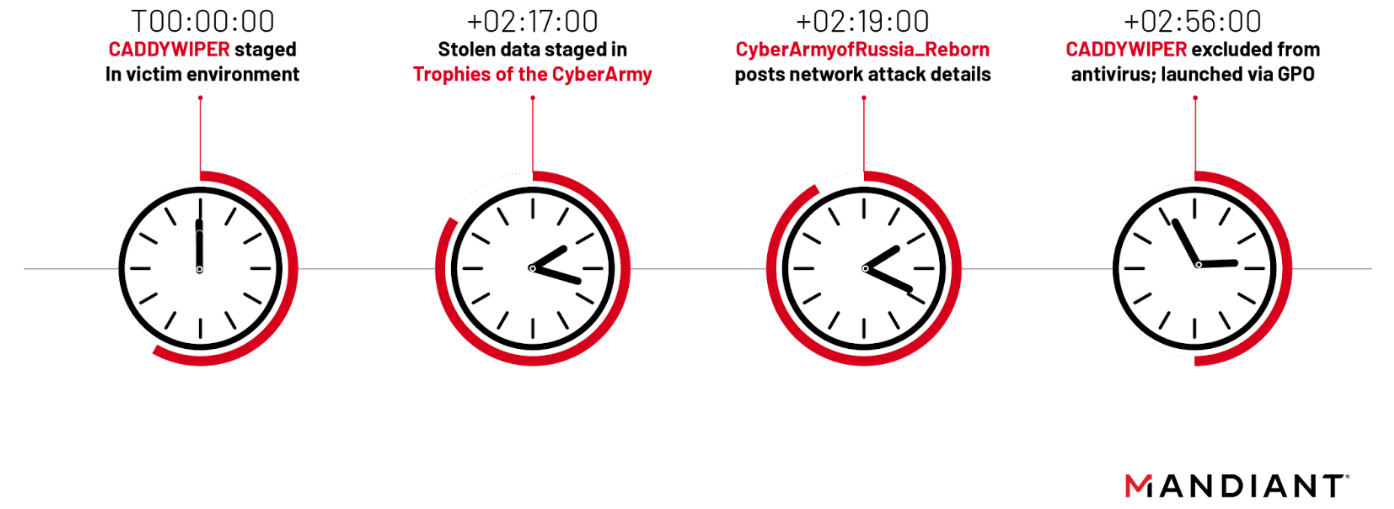

On 3 October 2022 at 07:34 UTC, UNC3810 staged the initial CADDYWIPER sample.

- Caclcly.exe

- CADDYWIPER x64 variant

- Compile time: 2022/09/18 10:17:23

A local antivirus client blocked the initial execution of CADDYWIPER during this operation, after which UNC3810 re-compiled and dropped a x32 CADDYWIPER variant to the target network, but did not configure any GPO to execute the variant via scheduled task. The attacker additionally attempted to exclude the file from antivirus scans. Mandiant assesses the x32 variant was likely successfully executed.

- Caclclx.exe

- CADDYWIPER x32 variant

- Compile time: 2022/10/03 10:01:48

Due to incompatible GPO configuration settings with the target system’s OS versions and the fact that the initial CADDYWIPER variant was only compiled to run on x64 operating systems, the impact of this disruptive operation was extremely limited. An obvious lack of preparation and reconnaissance on the target systems combined with proactive choices made by network defenders prevented UNC3810 from creating a significant disruptive impact in this operation.

Telegraphing “Success”

Disruptive operations rarely make headlines by themselves because their effects are not visible to the public, unless victim organizations choose to publicize the attack. To overcome this dilemma, the GRU has used a series of Telegram channels assuming hacktivist identities to claim responsibility for cyber attacks and leak stolen documents or other proofs from their victims. We assess this tactic is almost certainly an attempt to prime the information space with narratives of popular support for Russia’s war and to generate second-order psychological effects from the GRU’s network attacks. Follow-on influence efforts tend to exaggerate the success of the preceding cyber components and are carried out irrespective of the cyber operation's actual impact. Telegram has been the primary platform for these efforts, as channels on the social media platform have become the go-to source for unfiltered footage and updates from the war.

In the final stage of the playbook, data from the victim of UNC3810’s wiper attack was staged and advertised on Telegram by “CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn”, a self-proclaimed hacktivist persona that claimed responsibility for the wiper attack. However, technical artifacts from the UNC3810’s intrusion indicate that the “CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn” persona severely exaggerated the success of the wiper attack. Due to a series of operator errors, UNC3810 was unable to complete the wiper attack before the Telegram post boasting of the disrupted network. Instead, the Telegram post preceded CADDYWIPER’s execution by 35 minutes, undermining CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn’s repeated claims of independence from the GRU. Based on the close sequencing between the wiper deployment and Telegram posts, Mandiant assesses with high confidence that UNC3810 and Cyber Army of Russia engaged in forward operational planning to orchestrate the cyber and information operations components of the operation.

Repeat Offenders: Past is Prologue for Russia’s Disruptive Playbook

The individual components of the GRU’s wartime playbook have clear roots in its historical patterns of information confrontation. The component TTPs, such as the targeting of edge infrastructure, limiting the overall footprint on victim networks and hosts through living off the land techniques, disruptive tools disguised as ransomware, and the increasing use of intermediary or disposable tooling, have become fundamental components of GRU cyber operations over the years. What is different is the full-scale integration of these capabilities into a unified, repeatable playbook that has likely been tailored for use in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

A Shift to “Pure” Disruptive Tools

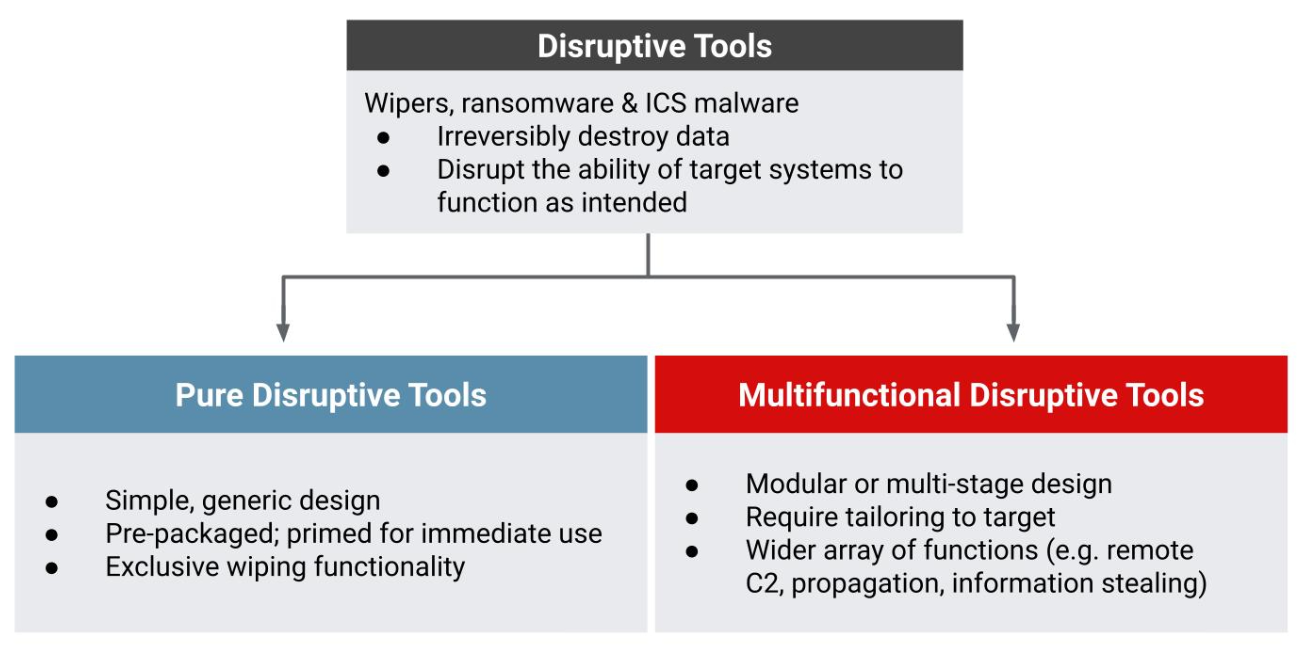

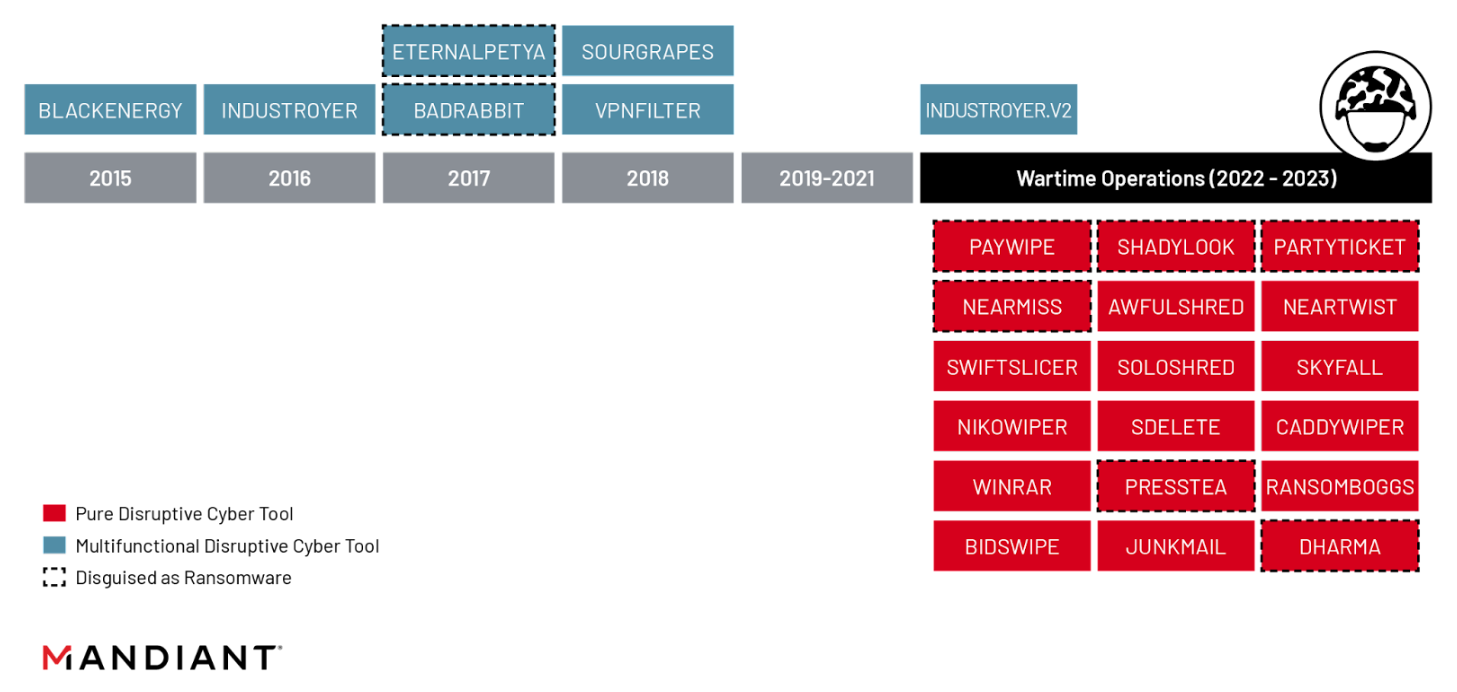

Following in the footsteps of its historical destructive campaigns, Russia has continued to operate a range of disruptive malware variants to include wipers, ransomware, and industrial control system (ICS) specific capabilities. While the general intent behind these tools — to irreversibly destroy data and disrupt the ability of target systems to function as intended — is similar, the design of the disruptive malware the GRU has chosen to use during the war is substantively different.

Since Russia’s invasion, the GRU has overwhelmingly opted to deploy what we call “pure” disruptive tools. This category of disruptive tooling is lightweight in design and primed for immediate use, containing only the capabilities required to disrupt or deny access to the target system. The generic design has made them disposable and functionally interchangeable, allowing the GRU to integrate new or modified tools into the wider playbook in a plug-and-play fashion to be deployed via GPOs. As an added operational benefit, disruptive tooling of this nature is freestanding, allowing operators to maintain minimal presence in the victim network and conceal the chosen malware variant until moments before its use.

This preference contrasts significantly with the GRU’s historical preference for “multifunctional'' disruptive tools that have been more complex, multi-stage or modular in design, and have contained added capabilities to carry out further objectives such as system reconnaissance, information theft, propagation to additional systems, or remote command and control. This category of disruptive tool is almost certainly more time and resource intensive to tailor and preposition, and at higher risk of detection, likely limiting the overall speed and scale at which they could have been used to achieve operational objectives.

Within this approach, the GRU has also continued to use disruptive tooling disguised as ransomware, including commercially sourced ransomware variants. Using ransomware highly likely serves the dual purpose of temporarily misdirecting attribution efforts and amplifying the psychological aspect of the operation, either through the ransom notes itself or via dark web forums or leak sites where feigned extortion attempts are often carried out. By incorporating commercially available ransomware and wipers derived from common software and utilities, we believe that the GRU has likely been able to more rapidly replenish its arsenal with new, undetected disruptive tools than it could have by developing them in-house.

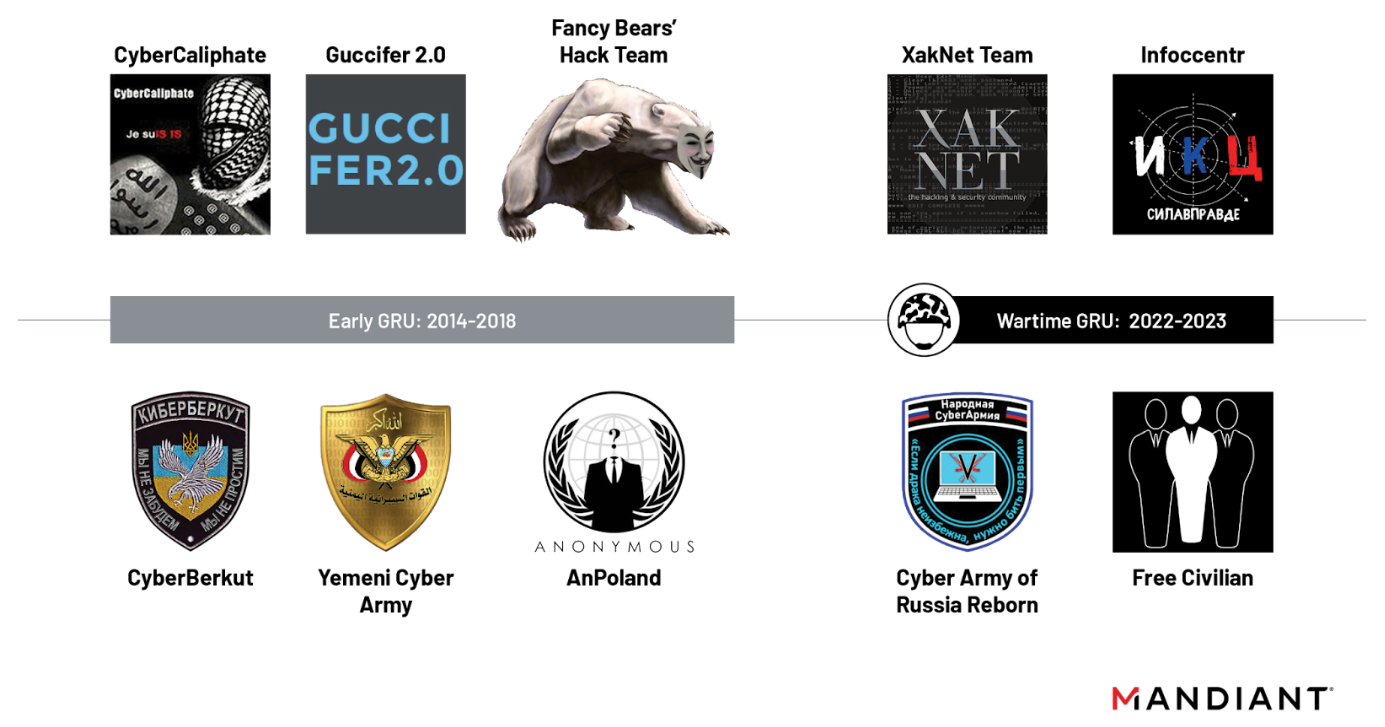

Integrating Hacktivist Identities Into Disruptive Operations

The GRU’s past tendency to exploit the identities and symbols of noteworthy political actors and hacktivist identities has taken a central role in its disruptive playbook. Extending back to at least 2014 and its original invasion of Ukraine, Mandiant has tracked what we assess as personas linked to GRU intrusion sets falsely assuming the identities of anonymous political and hacktivist groups in order to misdirect attribution and generate second-order psychological effects from their cyber operations.

- CyberBerkut: Between 2014 and 2018, the GRU assumed the identity of Ukraine’s dissolved special police force "Berkut" (Беркут) to conduct targeted leaks, website defacements, and distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks against Ukrainian and NATO government and military organizations. Notably, the group attempted to crowdsource support for DDoS attacks by calling for supporters to voluntarily install malware on their machines that would aid CyberBerkut's DDoS activity.

- CyberCaliphate: In 2015, the GRU used the CyberCaliphate persona (mirroring the pre-existing online persona used by the terrorist group ISIS) as a false front to claim responsibility for the network disruption of TV5Monde and a series of social media account compromises, website defacements, and leaks targeting Western media and military organizations.

- Yemeni Cyber Army: In 2015, the GRU likely co-opted the identity of a pre-existing anonymous hacktivist group “Yemen Cyber Army'' (the GRU fork being distinct in its use of “Yemeni”). The persona claimed to be a grassroots youth group responsible for stealing a cache of stolen documents allegedly given to WikiLeaks in response to Saudi Arabia’s role in Yemen’s civil war.

- Guccifer 2.0: In 2016, the GRU referenced the identity of the jailed Romanian hacker “Guccifer” to leak stolen and forged documents from the Democratic National Committee (DNC) as part of efforts to influence the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

- AnPoland: In 2016, the GRU leaked stolen documents and conducted website defacements and DDoS attacks against the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) under the false auspices of the hacktivist group Anonymous Poland, mimicking the real hacktivist group Anonymous.

- Fancy Bears’ Hack Team: Between 2016 and 2018, the GRU used a false hacktivist persona to conduct a sustained influence campaign against organizations associated with the Olympic Games and other sporting bodies, including WADA again.

Since the 2022 Ukraine invasion, Russia has further extended this approach, integrating similarly themed self-proclaimed hacktivist groups into its disruptive playbook. Overlaps in tactics include the continued appropriation of noteworthy hacktivist identities, crowdsourcing of operational support, and soliciting coverage that could amplify awareness of operations and their perceived impact through exaggerated claims of impact. What is newer is the central role of Telegram, which has emerged as a critical source of sensemaking, war-related information operations, and a key recruitment platform for volunteer cyber “armies” in the conflict. Notably, Mandiant has observed each of the GRU’s four wartime personas leak data from victims who were also affected by wiper attacks. In multiple incidents, the use of disruptive tools and data leaks have occurred within a short window of time, indicating advanced planning for the inclusion of the IO components in these disruptive campaigns.

- CyberArmyofRussia_Reborn: Beginning in March 2022, the Cyber Army of Russia persona, claiming to be a grassroots “People’s CyberArmy”, has been used to solicit coverage of destructive malware operations where CADDYWIPER was deployed, distribute tools and crowdsource DDoS attacks, leak stolen data, and to amplify accounts spreading propaganda regarding Russia’s battlefield progress.

- XakNet Team: XakNet’s Telegram channel was also created in March 2022, claiming direct lineage to a group by the same name that targeted Georgian entities during the Russia-Georgia War of 2008. The group carries out a spectrum of similar activities to Cyber Army of Russia, including soliciting coverage of network attacks, crowdsourced DDoS attacks, leaks of stolen data, and amplification of other pro-Russian Telegram accounts.

- Infoccentr: Again in March 2022, a Telegram channel “Infoccentr” was created that has engaged in the same spectrum of activities to include crowdsourced DDoS attacks, leaks of stolen data, and drawing attention to victims of CADDYWIPER operations.

- Free Civilian: Starting in February 2022, a self proclaimed pro-Russian hacktivist persona “Free Civilian” claimed responsibility for a series of government website defacements and advertised stolen documents for sale, using identical defacement images from the January PAYWIPE and SHADYLOOK wiper campaign. The persona resurfaced on Telegram on the anniversary of the invasion to claim additional defacements and leak alleged stolen documents.

Conclusions

The GRU’s disruptive operations in Ukraine have revealed a series of tactical choices Russia’s military has made to achieve its wartime information confrontation objectives. These adaptations have assisted the GRU to balance different strategic priorities for espionage and attack and to integrate its cyber and information operation capabilities into a unified, repeatable playbook that could be used across multiple distinct Russian threat clusters.

Many of the components of the GRU’s disruptive playbook are not new. They have been historically used in different ways. But in Ukraine, they have been uniquely combined and tailored to meet the requirements of operating at scale in a fast-paced and highly contested wartime environment while avoiding detection. As this playbook has almost certainly been purpose-built for Russia’s invasion, we judge that these specific tactical adaptations may be mirrored in future crises and conflict scenarios where requirements to support high volumes of disruptive cyber operations are also present.

It is important to note that this playbook is not wholly unique to Russia’s war in Ukraine. Financially-motivated ransomware operations also follow a similar playbook, abusing vulnerabilities in edge infrastructure for initial access, living off the land, and modifying GPOs to spread and execute their malware. We believe that the convergent use of these tactics is likely driven by a common desire to reduce the breakout time from initial access to malware delivery and to maximize the disruptive effect in a target environment. Consequently, preparations to monitor, detect, and respond to the TTPs used in Russia’s wartime cyber playbook will have transferable benefits for defending against tradecraft commonly used by ransomware groups as well.