What to Expect When You’re Electing: Preparing for Cyber Threats to the 2022 U.S. Midterm Elections

Securing the individuals, organizations, and infrastructure involved in elections from malicious cyber activity continues to be a challenge in an ever-evolving threat landscape as the number of threat actors targeting this important democratic process has grown over the years. Elections face the range of the adversary motivations and operations that Mandiant tracks across the globe—espionage threats, destructive and disruptive attacks, information operations, and criminal extortion.

The particulars of why an actor might target a specific election vary, and the lack of frequency of elections that an actor might decide to target can make it challenging to anticipate who, what, and how. As we observed in 2020, when Iranian actors impersonated the ‘Proud Boys’ organization to send threatening emails to voters in Florida, new election cycles can bring new threat activity, even if low effort. With an eye toward historic threat activity here and abroad, we can leverage past observations to prepare for and respond to a range of threats to the November 2022 U.S. midterm elections should they materialize.

Mandiant assess with moderate confidence that cyber threat activity surrounding the midterm elections will cause disruptions and divisiveness, but we believe notable compromises of actual voting devices or other activity impacting the integrity of votes is unlikely.

- In particular, we will likely see information operations (IO) that target U.S. populations around the election. We believe that Russia, Iran, and China remain the most significant foreign IO threats, having observed numerous examples of information operations that we suspected to support Russian, Iranian, and Chinese interests commenting on U.S. politics and 2020 candidates and issues, including activity intended to intimidate or influence voters.

- During the lead up to elections—as recent activity demonstrates—ongoing IO campaigns may pivot their messaging to focus on relevant political issues as part of their broader aims of sowing divisions within the U.S. populace, undermining democratic institutions, and promoting narratives aligned with each respective campaign’s interests.

- We are also highly confident that espionage campaigns will target U.S. election organizations, infrastructure, political parties, government, and other related groups and individuals. We have tracked activity from groups associated with Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, and other nations targeting organizations and individuals related to elections in the U.S. and/or other nations with apparent goals ranging from information collection and establishing footholds or stealing data for later activity to one known case of a destructive attack against critical election infrastructure.

- During the 2016 and 2020 U.S. presidential election cycles, we observed significant, multi-pronged campaigns involving information operations, including those supported by cyber intrusion activity.

- We assess with moderate confidence that disruptive and/or destructive activity, such as distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks or ransomware, will impact government and election-related organizations and infrastructure.

Recently Observed IO Activity Highlights Campaigns’ Pivot to Promotion of Narratives Around the 2022 Midterm Elections

Mandiant recently observed activity by three separate IO campaigns promoting narratives pertaining to U.S. political issues, including those surrounding the 2022 U.S. midterm elections. IO campaigns often involve the ongoing promotion of content targeting political discourse, including that supporting specific stances or politicians outside election cycles.

Previously identified IO activity targeting the U.S. and attributed to foreign actors has shown attempts to influence local or regional politics. While this may not directly correlate with a given actor’s interest in influencing a midterm election, such demonstrations at least signal their interest in influencing U.S. politics at the sub-national level. For example, various Russia-linked online and real-life influence activity has had local and regional U.S. targeting, including support for successionist movements in states like California and Texas.

“Newsroom for American and European Based Citizens” (NAEBC)

Mandiant has observed continued activity by two inauthentic personas, “Niels Holst” and “Alan Krupka,” that previously claimed to be editors at the inauthentic news website NAEBC. According to a Reuters article citing a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigation, NAEBC was run by individuals associated with the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA). While the news site itself is no longer accessible, a limited subset of the personas that we linked to the site remain active, and promote content targeting U.S. right-leaning audiences on the Gab social media platform. Recently, these personas have promoted narratives related to current U.S. political topics, including the midterm elections, the economy, energy prices, and Russia's invasion of Ukraine. Both persona accounts post semi-regularly, often reposting content from other seemingly unaffiliated users interspersed with seemingly original posts created by the accounts' operators.

DRAGONBRIDGE

Mandiant assesses with high confidence that social media accounts associated with DRAGONBRIDGE, an information operations campaign we judged to be operating in support of the political interests of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), are promoting content negatively portraying the U.S. political system and commenting on a range of domestic political, social, and economic issues, including on topics related to the 2022 U.S. midterm elections. Accounts highlighted economic and social issues facing the U.S., and portrayed the country as riven by political infighting and polarization. Utilizing a tactic first observed during DRAGONBRIDGE messaging targeting Western rare earths mining companies, some accounts posted comments using first-person pronouns to feign concern, implying that they were American.

EvenPolitics

Mandiant identified and reported to our customers on what we assessed with high confidence to be an inauthentic news site, EvenPolitics, promoted by a network of coordinated and inauthentic social media accounts, including those posing as U.S. individuals. We further assessed with low confidence that EvenPolitics and social media accounts promoting the site are operated in support of Iranian political interests. While the social media accounts have since been suspended, EvenPolitics has continued to publish articles including those on election-related topics, such as polling models forecasting potential election results, the Georgia Senate race, the Republican primary race for U.S. Representative Liz Cheney’s seat, the Arizona Republican gubernatorial primary race, and the Forward political party. As with other EvenPolitics articles, content appears to have been plagiarized and altered from original news articles published by mainstream media outlets such as The Week and The Guardian.

Activity Around Previous U.S. Midterm Elections

Mandiant has identified and reported on information operations serving foreign interests during the last three U.S. election cycles. For example, the pro-Iran "Distinguished Impersonator" influence campaign leveraged inauthentic personas impersonating U.S. political candidates running for office during the 2018 U.S. midterm elections to promote desired narratives. The campaign also successfully published letters, blog posts, and guest columns in local U.S. news outlets and leveraged inauthentic journalist personas to conduct interviews with real individuals which the interviewees expressed views in line with Iranian interests.

Cyber Espionage

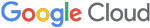

Based on recently observed activity patterns and/or past election targeting, including U.S. races, we anticipate that APT41, APT31, APT29, and APT42 are likely to target U.S. government and other election-related organizations. We suggest that this list could represent a useful guide for prioritizing defensive strategies and hunt missions for relevant government, civil society, media, and technology organizations ahead of the 2022 U.S. midterm election. However, this list should not be viewed as comprehensive; it is possible that additional known actors or previously unobserved groups will also engage in relevant cyber threat activity.

| Recent targeting of U.S. government or other election related organizations | Past targeting of U.S. or international elections | |

| APT41 | Mandiant observed multiple APT41 campaigns targeting U.S. state governments in 2021, including this campaign, which involved exploitation of vulnerabilities in USAHERDS and Log4J. | In July and August 2016, APT41 targeted Hong Kong media outlets using SOGU malware ahead of the legislative council election. The group likely targeted media organizations with spear-phishing campaigns due to their pro-democracy editorial content. |

| APT31 | Google reported that it successfully blocked an APT31 phishing campaign targeting "high-profile Gmail users affiliated with the U.S. government" in February 2022. | In June 2020, Google reported that APT31 targeted staff of the Biden campaign with phishing attempts. In October 2020, Google reported additional APT31 phishing of Biden campaign staff using spoofed McAfee credential collection attempts. |

| APT29 | Mandiant continues to detect and report APT29 phishing campaigns and third-party compromises that primarily appear to be targeting diplomatic and foreign policy entities in Europe and the Americas. | According to open sources, APT29 compromised the Democratic National Committee (DNC) ahead of the 2016 U.S. election, likely separately from APT28's concurrent compromise. |

| APT42 | Between March and June 2021, APT42 used a compromised email account of a U.S.-based think tank to target Middle East researchers at similar organizations, U.S. government officials involved in Middle East and Iran policy, and other individuals. | Microsoft and Google independently reported Iranian threat activity targeting U.S. election campaign staff and others in late 2019 and summer 2020. Mandiant believes that both reports refer to APT42 activity. |

Cybercrime

Many election-related organizations are also at risk of being targeted or impacted by ransomware and other types of cybercrime. Though this activity may not be driven by threat actors seeking to disrupt the electoral process due to political motivations, nonetheless it could impact business processes that may have cascading impacts to execution of the election. However, state-sponsored or affiliated threat actors such as UNC2448 may also leverage ransomware under the guise of financially motivated activity to disrupt the electoral process.

Hacktivism

Hacktivists may be motivated by election-related issues to conduct activities such as data leaks or website defacements with the intent of expressing a viewpoint or causing disruptions. Examples include a November 2020 data leak by a Portuguese hacktivist group that leaked what appeared to be old and possibly fabricated data regarding a Brazilian election and an Iranian hacktivist defacing a U.S. commercial website to display messages critical of the U.S. in advance of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. We also note that nation state-sponsored actors have a history of leveraging false hacktivist fronts as a tactic to support their operations, including those targeting elections. For example, the false hacktivist persona Guccifer 2.0 was leveraged by Russia’s Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff (GRU) as part of its targeting of the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

Insider Threats

Insider Threats have become a concern for election officials. In 2021, a judge barred an elected county official from supervising any future elections after it came to light that the official had allowed an individual not affiliated with the election commission to photograph and publish confidential voting-machine passwords, as well as making copies of the hard drives and changing settings on the machine that introduced security vulnerabilities into the process. Similar incidents have occurred in other states, speaking to a concerning rise in security breaches by insiders.

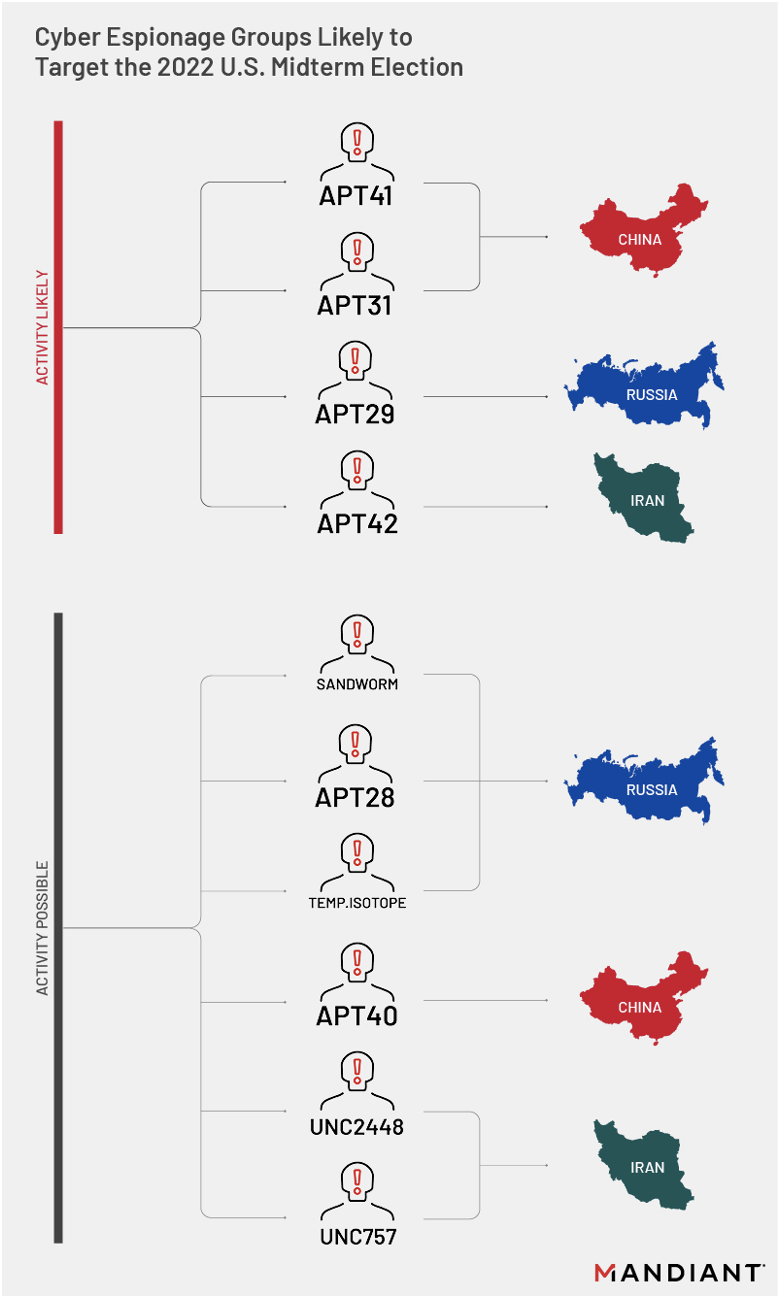

The Targets—The Election Ecosystem

Just as there are a broad array of threat actors, there is a diversity to where (and how) cyber threats to elections might play out. Cyber espionage and cyber attacks from state-sponsored actors, information operations, hacktivism, and even cybercrime can all pose a threat to entities evolved in elections in different ways.

At a high level, the attack surface of an election involves election systems and infrastructure, election administrators and entities involved in running the election, and organizations involved in the political campaigning process—to include news and media organizations that might be exploited or leveraged by threat actors. The ease of targeting and nature of threat activity (cyber espionage, information operations, extortion, etc.) can vary across entities within these categories.

Challenges and Considerations

In comparison with safeguarding other types of infrastructure or potential targets, election administrators and security practitioners face some unique challenges. It is important to emphasize that not all these threats represent an equal risk in impact to the electoral process.

- Event-specific activity: The reasons why a certain actor might target an election might vary from one event to another. In observance of election-related IO activity, presidential and general elections seem to be targeted at higher volume than midterms, based on the limited sample size of Mandiant and public third-party reporting. However, this assessment may be influenced by attention bias; it is likely that more defenders spend more time hunting for activity surrounding presidential and general elections than regional, local, or midterm elections.

- Assessing intent: One challenge in assessing risk from threat actors targeting elections is that the targeting of certain entities (such as state infrastructure) could be for purposes other than election-related threat activity; simultaneously though, a foothold in such infrastructure could also be leveraged in the future for election-centric activity. Visibility into specific data or victims targeted, as well as historical missions’ taskings attributed to a specific group may provide additional insight into adversary motivations.

- Communication of threats: As trust in the electoral process is essential, communication of the details of an ongoing incident that may occur during an election—with stakeholders being the broader public—increases the complexity of response. Timely communication of what targets were impacted and in what manner becomes an important component in ensuring trust in the process that election administrators must navigate.

A historical understanding of threats to election participants and infrastructure—and global visibility into current operations by threat actors that have demonstrated an interest in targeting elections—can prove valuable for security teams to scope, prioritize, and anticipate future threat emergence. Threat intelligence that informs and provides visibility into the recent tools, tactics, and procedures of such threat actors in other operations can better arm election defenders. Organizations can operationalize such insights to proactively harden networks and potential targets to better prepare for threats to this critical democratic process.

Head over to our election security page for more on how Mandiant is helping to secure elections.